A conversation on racism in cycling with Dr. Tim Erwin

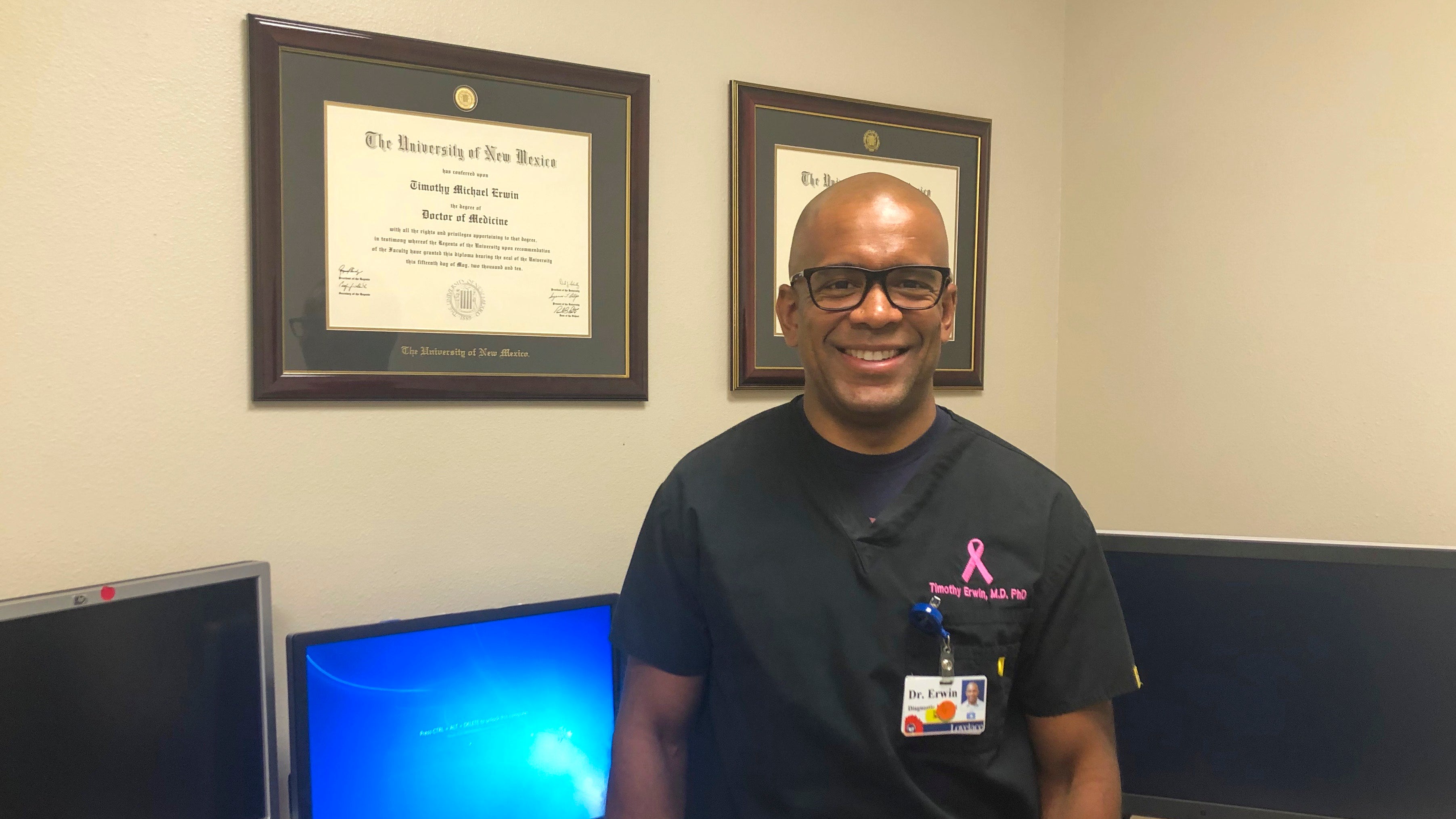

Tim Erwin, MD, PhD, is a radiologist in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Decades ago, two guys were instrumental in getting me into bike racing and thus my career, and we’ve been friends for more than 20 years since. Tim Erwin found cycling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, before spending a year studying and racing in France. Cameron Tongier picked up the bike habit in the Army when stationed in Italy.

Tim and Cameron taught me about cycling: The tactics, the culture, the training, the gear, the personalities. Cameron loaned me VHS tapes of European races. Tim wrote training plans for me and gave me lactate threshold tests.

We raced together collegiately in New Mexico and then on a little team called D Low Cycling. Tim got further than Cameron or me, earning a UCI license and racing on the domestic pro circuit before going to medical school.

Tim is black. Cameron and I, like the vast majority of the cycling world, are white. Tim is a radiologist in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Cameron works for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in Boise, Idaho. And I’m editorial director at VeloNews in Boulder, Colorado.

Like many people, the three of us have been doing virtual happy hours recently, and this Saturday we talked about racism in cycling. What follows are excerpts from that conversation.

Three cycling amigos in New Mexico in 2000: (l to r) Cameron Tongier, Ben Delaney, and Tim Erwin.

Tim Erwin: The first time someone calls you the n-word — for me that was in second grade in Louisiana — from the time you perceive you are different, you carry this load around like bricks in a backpack. You move like that. I’m 180, but I move like I’m 220.

The Ahmaud Arbery case really hit home. I think it’s because I go for runs and bike rides, and when I’m out there I’m super vulnerable so I realize that that could easily be me or any other black man in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Being black can feel like you are screaming into the void. We’ve said that these things happen, and then they happen again, and again, and again, but nothing changes. Now, with actual footage from cell phones or body cams, it’s undeniable.

I see the protests and they give me some hope, but ultimately I worry that nothing of consequence will happen because it’s so ingrained in the culture. I hope I’m wrong.

You know, there are all levels of racism from the microaggression to the blatantly racist. You know, for example, from someone telling me “you are so articulate,” up to someone yelling “white power” at me when I’m riding up Tramway (a road in Albuquerque).

Erwin racing in Louisiana in the ’90s.

Cameron Tongier: I saw a bunch of bike companies posting on social media. What did you think about that, Tim?

TE: I didn’t know how to feel about it at first. The question is, is it lip service? They have been part of the problem for so long. It’s been whites-only at the highest levels for so long. Reading the article with [Rahsaan] Bahati was like reading my own thoughts and I think that speaks to the commonality of the black experience in cycling. Like, the suspicion that comes with having a nice bike. I can remember taking my own bike into a shop in Louisiana, and getting asked “Did you steal this bike?” The average white person gets talked down to in shops a lot of times; the average black person gets talked down to and is assumed to be a criminal.

Speaking of Bahati, you can’t tell me he wasn’t as talented. He was, he just wasn’t as nurtured as his peers.

I like what the Williams brothers are doing. Specifically, that they are doing things on their own terms. I remember seeing the report from Tulsa Tough when Justin Williams won and I was like, “WTF? Is that a black dude who won?” It was really awesome to see that happen.

I don’t know what the cycling industry can do; I think you just have to make racism anathema. Like Amy Cooper, she suffered real consequences and I think that’s what has to happen. It has to be clear that there’s no place for it and it won’t be tolerated.

CT: In pro cycling, Gianni Moscon, he’s still riding for Ineos. Or Michael Albasini. Those guys shouldn’t be in sport. There should be a zero-tolerance policy.

Ben Delaney: Tim, you talked about a spectrum of racism. How does that look in cycling?

TE: Well, there are things like being in a race and having things said to you that wouldn’t be said to anyone else. For example, years ago at the [Tour of the] Gila crit I was in a little move with a guy and I skipped a turn and he was like, “pull through, boy!” I wanted to crash him, but I can’t, right?

Then there are less blatant times when your Spidey sense is tingling. Like at a crit in Pensacola, Florida a long time ago. I was a junior racing in the senior race and I won and threw my arms up crossing the line. They were going to DQ me for that. It took my white teammate getting in the official’s face for him to back down.

Some of it is you’re pigeonholed, like “oh, you’re black, you’re going to be a good sprinter.” Those are egregious. Sometimes, you just wonder if you’re being singled out because you’re black. I remember doing the Colorado road champs in ’99 and guys were just making comments, like “watch your line!” seemingly the whole day. I’m a good bike handler. I wasn’t bouncing around. And I ultimately got second in that race.

Erwin racing at the 2000 Capitol Cup (left in red jersey), and winning a stage of the Tour de Louisiane.

It can even show up on training rides. I remember once on a ride not long after I had moved to New Mexico someone was driving it uphill and people were getting dropped. I heard some yelling from behind as things were breaking up and after we regrouped I asked what happened. Someone said “I’m not going to say what she said,” referring to a lady on the ride. From the look on their face I’m pretty sure what she said.

Or at another race in Louisiana once, I was in the break and one of the guys starts yelling about my pulls and sneers “brother” after he was done. It escalated and escalated until we were about to pull over in the middle of the race. Afterwards he came up and said sorry. And in that situation I couldn’t really say what I would have liked to because I would have been seen as the aggressor.

CT: I think a black person is seen to have an expectation to accept those apologies.

BD: Speaking of things on the spectrum, I have to ask you about something I said during a race years ago. At the last stage of Tucson [Bicycle Classic] we did the leadout for you, and Cameron went, and then I went, and as I swung off I said —

TE: “Go, dog”?

BD: Yeah.

TE: I remember it. It’s funny that you didn’t have to finish the story and I knew what you were talking about. Like that happened and it obviously stuck with both of us. I guess I gave you a pass because you’re my friend and I knew that you didn’t mean anything by it. That’s the thing; it happens.

BD: Maybe, but that doesn’t make it okay. I apologize, Tim.

TE: I appreciate that. You know, it’s like when I go through the line at Whole Foods or wherever and I get a “hey, brother,” or a “hey, man.” I mean, I’m old now; I want a ‘sir’ like anyone else. People just get too familiar.

CT: To play devil’s advocate, some people I think say the wrong thing, not from bad intention, but because they don’t know enough or just don’t know any black people. They still need correction. And not to excuse it, but they aren’t doing it from a point of bad intention. A pass is not deserved, but perhaps punishment is not either.

TE: Being black means you have to think about these things every single day. For example, if I’m shopping and I see something that I’d like, within reason, I can figure out how to make it happen. But when I do buy something I always get a physical receipt just in case. You know just in case the clerk forgets to deactivate the security sensor and the alarm goes off. It almost doesn’t matter what level of success you attain, you still have to give energy to this and it can wear you down. I imagine celebrities can afford to insulate themselves from it for the most part, but the average black person can’t and has to deal with it.

These are difficult conversations. Even if you are close to someone, it’s hard to talk about. Ben, to your point about that Tucson incident 20-plus years ago, we never talked about that until now. What about people who don’t have black friends in their life? Where are they going to get this perspective?

Erwin started racing as a junior in Louisiana, and raced pro in 2000 for Yahweh-Tokyo Joe’s-Pepsi.

CT: Where cycling journalists should have done a lot better is with the case of Moscon [saying racist things], they should have been chastised. Next time that comes up, it should be an unequivocal, “We condemn this. This person should be dropped.” Make that clear.

TE: Any time you get that slap on the wrist, it gives you license. Moscon seems like a dyed in the wool racist. He happens to have some talent, and that is providing him with some protection.

The net effect of these constant reminders that you’re an outsider is to make you think, ‘maybe I’m never going to belong and I shouldn’t be doing this.’ That’s the impact. [Justin] Williams and Bahati have both mentioned this I think, that any black person who exists in a white space like cycling has to check a part of themselves at the door. At work [as a radiologist] I have to present myself in a certain way, almost to not make patients uncomfortable. It has only happened a couple of times, but I have had some racist interactions. Once I walked in for a biopsy, and after I introduced myself the patient said, “The lord told me I was going to see a black man today. No black man has ever touched me.” Those were the first words out of her mouth. Her husband was mortified. He apologized. I said, “Don’t worry about it, I will call you with the results.”

BD: What was your experience riding in France?

TE: I think I was somewhat of a novelty there. You know, they just don’t have the same history. But it’s hard for me to say because I have a romanticized memory of that whole experience. Although I did feel very much taken in by the club I rode for there, maybe because I spoke French. That was 1993-94.

The racism here, it’s incomparable. Years ago when I was racing in Louisiana, an official and her husband were always nice to me. But I remember once after I had just finished a crit as a junior, we were all in this little group chatting and the husband had a breathe right strip type thing that flared his nostrils. I asked him about it and his wife said, without skipping a beat, “oh, that gives him his n— nose.” I was 16 I think and I said, “What did you say?” She fumbled her words and said, “Ah, um, I will buy you a snowcone,” as if that would make everything okay. That was 30 years ago but it is just another example of the things I’ve personally experienced.

CT: How do you get people of color interested in the sport? Boise [Idaho] is so white. As a team manager, I’m thinking about, one, how to find talent, but also how to branch out with inclusiveness.

TE: I’m not sure of the best way to go about it but I am sure that people need to see people who look like them being successful to know that it is possible.

God only knows why I got into bike racing in the deep south. There certainly weren’t many people who looked like me doing it at the time. There was one other black dude. If there were two of us in the same race, it was like seeing Bigfoot and a unicorn on the same day.

To get more minorities into the sport, I think you have to address the economic hurdle. Cycling is an expensive sport and we all know that in cycling, you get what you pay for. A $7,000 bike is better than a $2,000 bike. I’m not saying that you need that caliber of bike to start but the financial issue has to be remedied in order to get increased participation. And when a black rider does show promise they need to be given the same opportunities to train and race and be supported just like anyone else.

Delaney, Erwin, and Tongier in a more recent year.