Everesting for a cause

Emma Grant everesting. Photo: Emma Grant

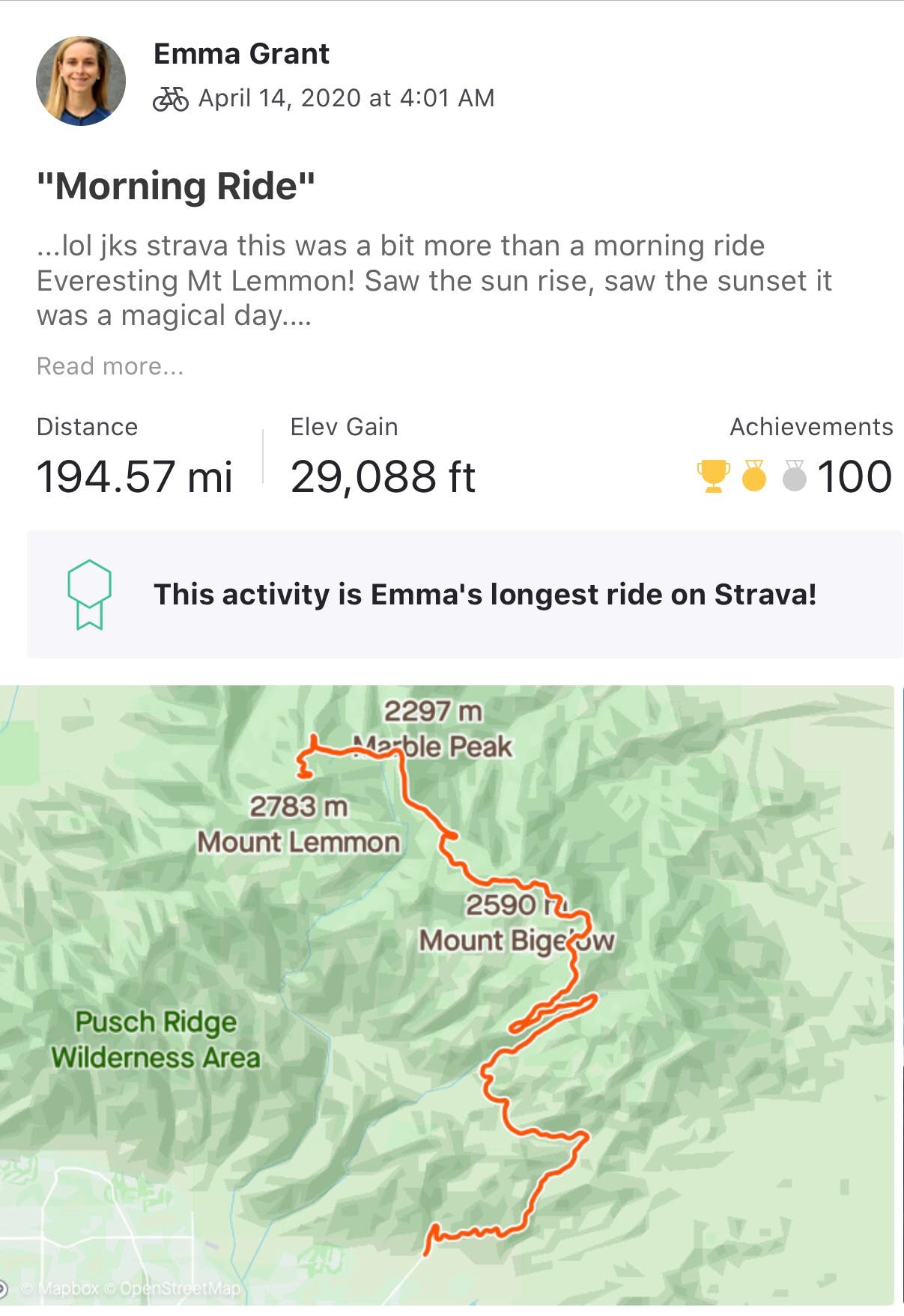

Most attempts to “Everest” something (to pick any hill and complete repeats of it in a single activity until you climb 8,848m – the equivalent vertical elevation of Mount Everest) are only possible with the help of friends and family who will support you along the way. When Twenty20 rider Emma Grant started her Everest attempt up Tuscon’s Mt. Lemmon at 4:00 in the morning on Tuesday, she was accompanied by someone she’d never met, who had to ride six feet away from her, in the dark.

So are the times of the coronavirus pandemic.

Finding themselves with an abundance of time during a season when they’re usually in full-on race mode, cyclists across the globe have found creative ways to pass the time. From baking to tinkering to cleaning up local roads, riders have shown that they’re talented off the bike, as well. As the short and long-term repercussions of the pandemic become clearer each day, many riders are infusing their free time, and their rides, with more meaning than ever.

Grant, who is spending the spring in Tucson, had been asking herself some of the same philosophical questions that many riders have been grappling with in recent days. Things like, “What am I doing, I don’t even know why I’m training,” Grant told VeloNews. It was on one of her meandering rides that she listened to a podcast about an “Everest” attempt. She thought it sounded like a brilliant idea; even better, was the fact that she’d been wanting to do something for charity.

Grant completed her Everest of Mt Lemmon at 8:00PM on Tuesday; it took four laps of the 7,272-foot climb, and about 15 hours to reach her goal. Grant says that the epic effort wasn’t nearly as challenging as a bike race.

“It wasn’t,” she says. “Because it wasn’t about me, not about evaluating a result. It was a journey, something a lot more meaningful.”

Like all cyclists, Grant is used to digging deep, but one thing she’s never had to experience is a lack of access to food. Earlier this year, Grant was recuperating from a foot injury with a host family in Tucson where one member of the household was a teacher. Grant was struck by her stories of homeless children who came to school hungry.

“I was at their house with a broken foot, feeling sorry for myself and she’s telling me about these kids,” Grant said. “Then, when coronavirus hit and people were panic buying and I was walking through stores that were barren, I thought about those kids, not being at school and not being fed.”

The combination of a desire to add meaning to her riding and the knowledge that kids were losing out on one, maybe two, meals a day with school being canceled led to Grant’s idea to combine an Everest of Mt. Lemmon with a donation to No Kid Hungry, an organization dedicated to feeding kids across America. So far, she is just shy of her $7,500 goal.

Two-time world champion Amber Neben is another cyclist who’s stepping up to help fill children’s plates. During the weekend of April 24 – 26, Neben is hosting the Three Summit Challenge, a weekend of virtual riding on the RGT virtual cycling app. Each day, Neben will join riders on a storied European climb: Cap de Formentor in Spain, Stelvio in Italy, and Ventoux in France.

“I wanted to create a fun, “stay at home” weekend for cyclists,” Neben said. “You could consider it a virtual get-away weekend.”

Like Grant, Neben has chosen No Kid Hungry to be the beneficiary of the donation-optional ride. Since the coronavirus crisis began, No Kid Hungry has given $3.9 million dollars to 147 organizations feeding kids across forty US states and Washington DC; 63 percent of those organizations are schools. Neben said that the breadth of the organization’s charitable work appealed to her.

“I thought this would be a good way that the riders could give back if they wanted to ride for a cause that could reach into their own areas,” she said.

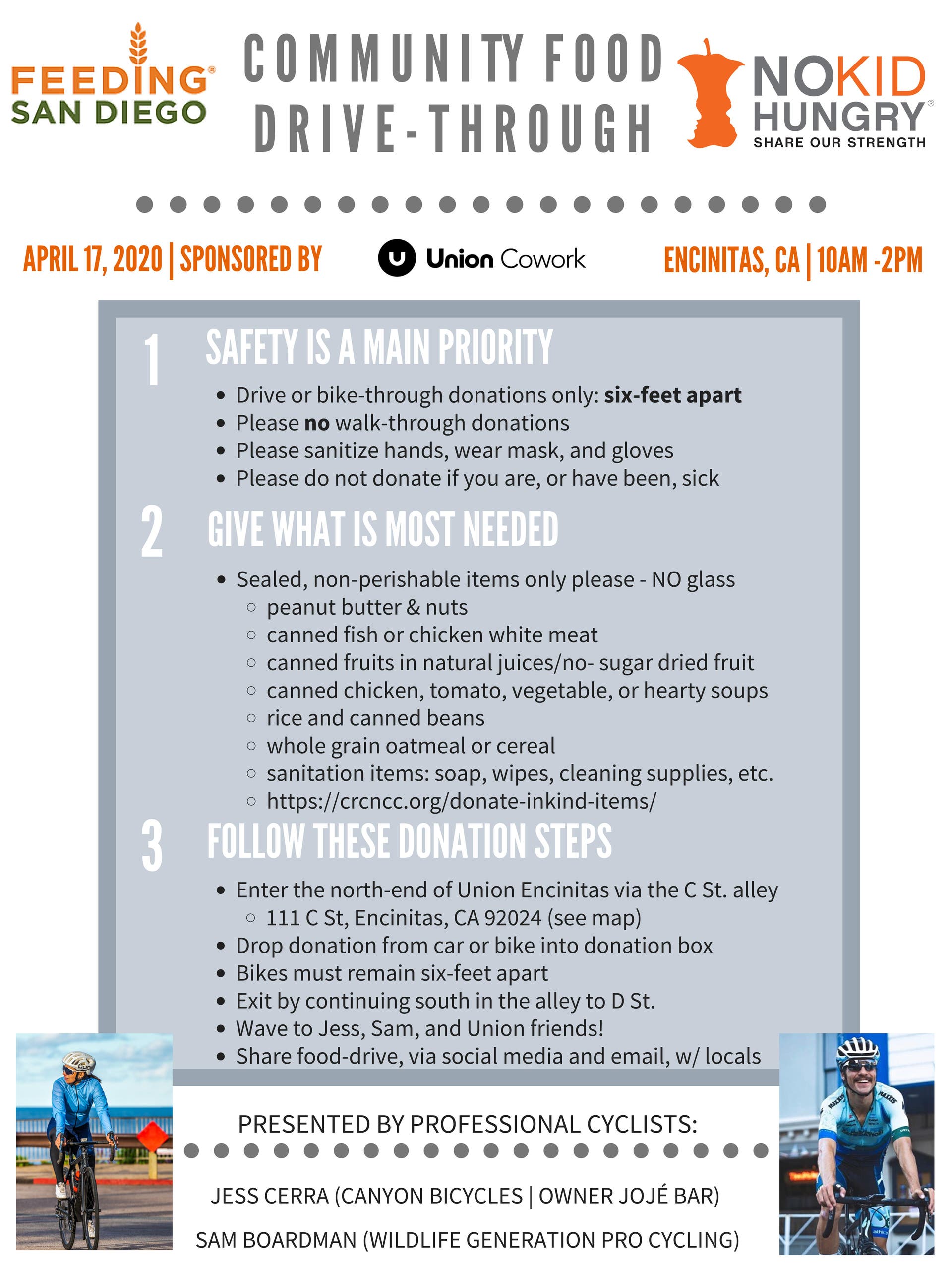

For Jess Cerra, formerly of both women’s teams Twenty20, and Hagens Berman Supermint, getting involved locally made the most sense for her. When she reached out to the hunger-relief charity Feeding San Diego and found out that they weren’t taking volunteers due to social distancing guidelines, she brainstormed other ways to help. Cerra and her boyfriend (Sam Boardman, who rides for Wildlife Generation) figured out that they could benefit Feeding San Diego in a different way.

“We’ve organized a no-contact drive and bike-through food drive,” Cerra says. “All the donations we collect will go to Feeding San Diego.”

Cerra is no stranger to food insecurity. She grew up in a single-parent home and her mother, who cleaned houses for a living, would sometimes bring home food from jobs or that clients had given her. This indubitably contributed to Cerra’s career choice: she’s been a chef for 12 years. A few years ago, she got involved in Chef’s Cycle, the fundraising endurance event that also raises cash for No Kid Hungry.

Although the abundance of time that a demolished race calendar has presented to cyclists has been challenging in many ways, Grant, Neben, and Cerra, among many others, show that cyclists are in a unique position to use the period of uncertainty for the greater good. It’s as simple as finding something you’re passionate about and investing some time.

“We are influencers,” Cerra says. “It’s our social obligation to do something like this.”