Major Taylor Journal: Why I ride

Named for Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor, the country’s first Black cycling champion, and the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, an all-Black unit known as the ‘Iron Riders,’ the Major Taylor Iron Riders club of New York City is comprised largely of Black, Latino, and Asian-American riders. These riders have informed perspectives on what it means to be a person of color in the U.S. cycling scene. We are honored to share their thoughts in a regular column series on velonews.com in the coming months.

I’ve been riding a bike since Gerald Ford was the POTUS, or as us old heads like to say: “The President of The United States.”

Much like Ford, I wasn’t anything special on the bike. I learned how not to crash, by crashing and then figuring out that I did not appreciate that part of the experience. Through my years of riding, I met like-minded kids that too, just wanted to ride their bikes. The exceptional amongst us were few, but skill wasn’t what brought us together; it was the love of riding and tasting that sense of freedom.

My friends were from all backgrounds and the bikes we rode reflected that. The bigger point of the experience was hanging out and having fun. Bikes bring people together.

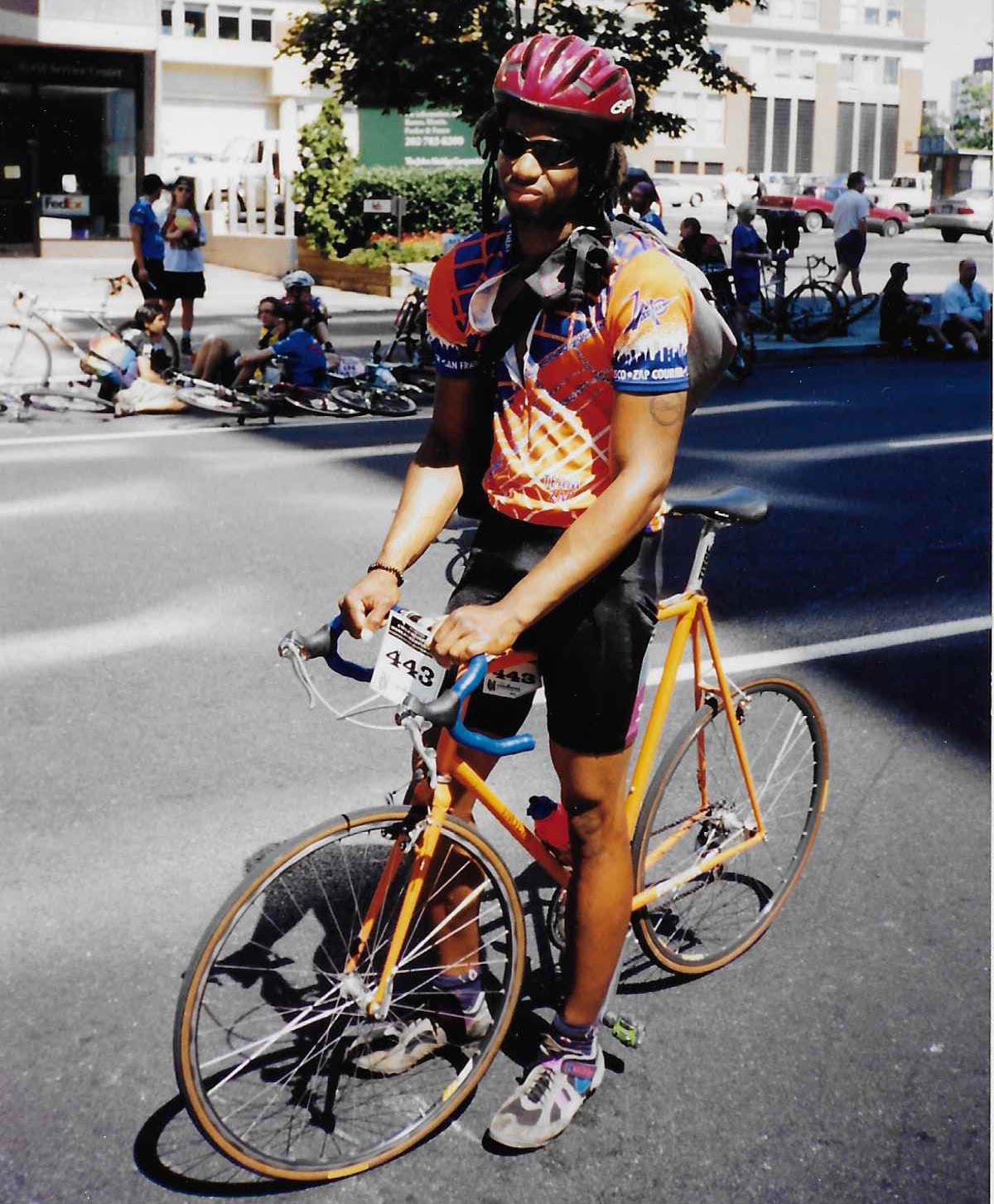

I rode as a messenger for 10 years, and I frequented bike shops a lot. From the posters on the walls, I saw a lack of representation of people who ride and look like me. From the professionals like Miguel Indurain, to the weekend warriors, to the families on bikes, white people comprised the landscape of cycling.

At that time, as a messenger, I really didn’t think about the lack of representation of people of color in cycling. You were either a competent rider, or you weren’t. We all looked out for each other. That didn’t mean that we all got along, but color means less when all you want to do is make it home safely.

When I hung up my u-lock for good and started riding for pleasure, I noticed that something was amiss. I would go into shops after having biked for years, and would feel the privilege in the air. From the attitudes towards me — a Black man — to the lack of people of color working in the shops, I felt alienated. It was as if white people had cornered the market on cycling, because it was their last bastion of segregation. Basketball had gone vertical, making Black men gods; white boxers only won in the movies; the Packers had soul; and baseball’s “peanuts and cracker jacks” were being replaced by Chicharron and Mofongo.

So, I searched for a new cycling family. I didn’t care about color as much. In my experience, bikes brought people together. I was counting on that theory to lead me to a new community of cyclists, but this was not the case. I’m a lifer to this sport and I felt as though I had to prove that I belonged. After logging thousands of hours delivering packages, avoiding death, and struggling just to make a buck, my worthiness to belong to the U.S. cycling community was still in question.

I’m happy to let you know that this feeling is slowly dissipating. With more people of color entering the sport, that feeling of not being enough wears away every year. It’s not uncommon anymore to see a group of cyclists that aren’t all a different shade of white. And, as I’ve learned from talking with the Black cyclists I’ve met, we spend as much money as other demographics, and we live and sometimes die at this sport, too.

I’ve learned other facts about the cyclists of color who are now on the road. As it turns out, we have a lot in common. Cycling isn’t just a hobby for a lot of us. For me, cycling is a lifestyle that sometimes feels like a life sentence. This life chose me and I don’t see an easy way out. I’m OK with that. I see other other riders of color on that same path. One day, it’s something that you do for fun, and 30 years later, it’s who you are. When I ride my bike(s), I am not representing my race. I am representing anyone that rides to exhaustion, through pain and the elements. I am representing those other cyclists who understand that there is nothing else we’d rather be doing. That feeling doesn’t belong to any one tribe. It’s powerful and it’s universal.

Throughout my time in cycling I’ve seen people enter the sport for all different reasons. I see more Black people riding for health first. “Good living,” as we all know, can come with hefty consequences on your body. I see Black people starting to ride for other reasons as well. More people of color are inclined to do activities when they see someone who looks like them doing that activity. Again, we are no different than any other group of people that sought safety in numbers.

The Major Taylor Cycling Network has chapters all over the United States, and has done excellent work in getting asses on saddles. The clubs also participate in community outreach. Cyclists are what we are and we want to see our sport grow. We also want to see our communities thrive, and if we can help get more folks under the umbrella of cycling, then I say, “let it rain” (not too much, of course, because creaky bottom brackets are the worst!)

At the end of the day, I just want to turn the cranks. I want to point my wheels somewhere and find something new, be that in a new part of the world or a new part of myself. And I can see from my growing community of riders that I am not alone.

The first time I ran away, I rode away. I packed up my backpack and hopped on my bike, because I was sick of being eight years old. I knew things my parents didn’t. I figured I could make my own way. My only friend in the world was my bike. My bike was my proverbial Wilson from the movie “Castaway.” Only my Wilson never floated away.

Bicycles have always represented freedom to me. The bike is my ticket to wherever my legs could take me. I’m sure I speak for a number of people that may look something like me, and even those who don’t. The whole point of inclusivity in cycling is that our love for the sport is no different than anyone else’s love for the sport. We just need to know that the sport that has become our love, and loves us back. That’s all we’ve ever asked of it.