For a few moments, it looked like Brandon McNulty (USA) might win the Tokyo 2021 Olympic Men’s Road Race. The 23-year-old American went clear of the lead group with less than 25km to go after a long day in the sweltering heat. He and Richard Carapaz (Ecuador) made it over the decisive climb of Mikuni Pass, and countered a string of attacks with what proved to be the winner.

However, with 5km to go, the American’s legs began to crumble beneath him, betraying the incredible form that had put him in the position to win gold. But he could only watch as Carapaz raced into the distance. The Ecuadorian smiled like a kid on Christmas morning when he crossed the finish line for the final time, winning Ecuador’s first gold medal since Jefferson Pérez won the men’s 20km walk in Atlanta in 1996.

McNulty’s story was one of triumph and satisfaction – the American wasn’t disappointed in his 6th place result at the end of the day. He believed he could win, he tried his best, and he came up short. Canadian Mike Woods had a similar story. He had some of the best legs of the day, but was too heavy a favorite to be let off the leash. Wout van Aert (Belgium), another race favorite, closed down every one of the Canadian’s attacks, Woods said after the race. He tried and tried again, just like McNulty, until the elastic snapped and it was McNulty and Carapaz who went up the road.

The Olympic road race is a unique event because the courses, terrain, and weather are so incredibly different at each of the Games. In 2021, half of the Tour de France peloton flew from Paris to Tokyo with just a few days of preparation before the 232km Olympic road race. Another interesting note: one might think that a three-week grand tour, and then transcontinental travel a few days before the Olympics was a bad idea… Not quite. Out of the nine riders — including Carapaz) — who made the lead group in Tokyo, eight of them came straight from the Tour de France. The only rider who didn’t race the Tour: Adam Yates, who finished 9th.

The Tokyo 2021 Olympic road race covered 232km and five categorized climbs, including Fuji Sanroku (14.5km at 6 percent) with 94km to go, and Mikuni Pass 96.8km at 10.1 percent) at 31km to go. After the final climb of Kagosaka Pass (2.2km at 4.6 percent) at 22km to go, the riders descended down to the Fuji International Speedway which included one final uncategorized climb that would become one of the most crucial points of the race.

As we typically see in the Olympics and world championships – one-day 200+ kilometer races raced by national teams, not trade teams – a small and relatively weak (but not to be underestimated; see: Olympic women’s road race) breakaway of eight riders were let go in the early kilometers. They were granted a 19-minute lead at one point, but they hadn’t a chance against Belgium and Slovakia who led the chase.

Although the pace wasn’t particularly high at that point of the race, the heat and humidity were beginning to take their toll. This is the reason that we don’t see crazy power numbers from this road race – one of the biggest limiting factors of endurance performance is core body temperature. If we get too hot or too cold, our performance tanks. We saw this at the Tour de France, when Tadej Pogačar (UAE Team Emirates) simply rode away from everyone on stages 8 and 9. Was he really on another level, or was everyone else cold, wet, and slow? Power data support the latter.

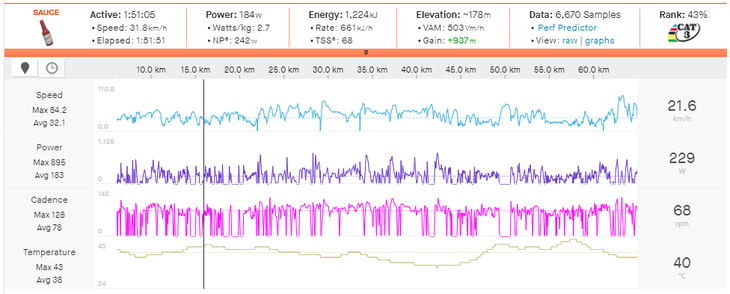

In Tokyo, temperatures reached 35 to 43C° (95 to 109F°) and 58 percent humidity. Those are not peak performance conditions. A number of race favorites seemed to be far from their best in the heat, including Remco Evenepoel (Belgium), Richie Porte (Australia), Nairo Quintana (Colombia), and Alberto Bettiol (Italy) who would eventually cramp after making the lead group. McNulty went as easy as possible during the first third of the road race, averaging less than 200w as temperatures climbed above 40C° (104F°).

McNulty – hottest part of the day:

Time: 1:51:05

Average Power: 184w (2.7w/kg)

Normalized Power: 242w (3.5w/kg)

Average Temperature: 38C° (100F°)

Max Temperature: 43C° (109F°)

As the peloton approached Mount Fuji and the Fuji Sanroku climb, reigning Olympic Champion Greg Van Avermaet (Belgium) took over the chase and brought the breakaway’s gap down to 11 minutes. It wasn’t long after the longest climb of the race that the breakaway’s gap was down to only five minutes. This part of the race was relatively easy for McNulty, whose FTP is well over 400w.

McNulty – middle portion of race:

Time: 2:35:36

Average Power: 262w (3.8w/kg)

Normalized Power: 316w (4.6w/kg)

The action began to heat up well before Mikuni Pass, the hardest climb of the race, and one that many were calling on riders like Carapaz, Woods, and Pogačar to attack. With riders like Wout van Aert climbing like a mountain goat and winning on the Champs-Élysées, the rest of the world needed to do something bold or the Belgian would ride away with gold.

The first 5km of Mikuni Pass averages 12 percent, with the final 2km averaging just under 7 percent. Over the course of 20-25 minutes, the Olympic Men’s Road Race was going to explode. Belgium led the way on the lower slopes, with Mauri Vansevenant pulling until there were just 15 riders left. After he swung off, Pogačar attacked, and only McNulty and Woods were able (or chose) to cross the gap. With still 37km to go, the trio wasn’t keen to roll the heaviest turns, and Woods mostly sat on until the upper slopes of the climb. McNulty traded pulls with Pogačar, and the leading trio gained a 20-second advantage over the chase group containing van Aert and Carapaz.

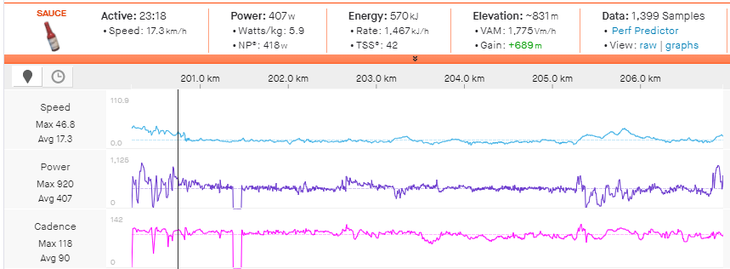

McNulty – Mikuni Pass:

Time: 23:18

Average Power: 407w (5.9w/kg)

Normalized Power: 418w (6w/kg)

Following Pogačar: 11:06 at 420w (6.1w/kg)

Woods – Mikuni Pass:

Time: 23:19

Average Power: 356w (5.6w/kg)

Normalized Power: 362w (5.7w/kg)

Following Pogačar: 11:07 at 363w (5.8w/kg)

On the steepest part of the climb, both McNulty and Woods rode at 5.9-6w/kg, but it’s on the upper slopes that Woods saved the most energy. As McNulty continued pushing the pace, Woods sat in the draft, and was able to stay in the lead group at less than 300w for the last couple of kilometers on Mikuni Pass.

Behind, van Aert went into time trial mode, and eventually closed the gap to the leading trio just before the top of the climb. There were now just 11 riders left in the front group, and with 30km to go, it was all to play for. The riders’ fates could be anything from Olympic gold to missing out on the top-10. Attacks flew every few hundred meters, with van Aert closing down most, and Pogačar covering others. After 5km of nonstop attacks, McNulty threw in a clever counter that only Carapaz reacted to. And just like that, they were away.

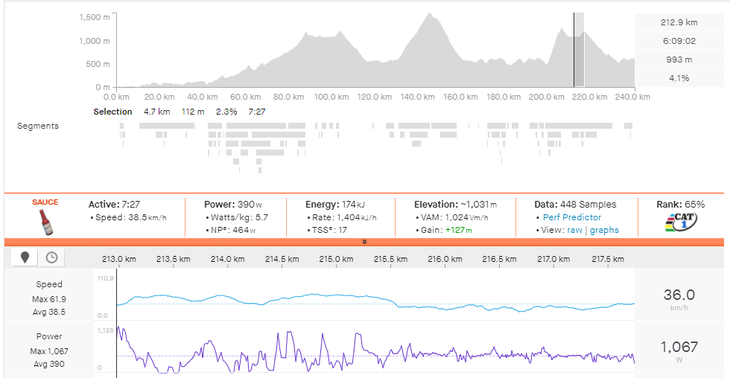

McNulty – establishing the winning move:

Time: 7:27

Average Power: 390w (5.7w/kg)

Normalized Power: 464w (6.7w/kg)

Max Power: 1,067w (15.4w/kg)

The leading duo worked together all the way down the descent and on the early parts of the Fuji Motor Speedway. But not to be forgotten, there was still one more climb: an uncategorized ramp up to the finishing circuit. It didn’t look like much on the race profile, but this deep into a six-hour race, it was enough to break the legs of McNulty. Carapaz didn’t put in much of an attack, rather, he kept up his pace as McNulty swung off. We can see in the American’s power file just how painful this moment was. It’s easier said than done, but with 30 more watts, and McNulty would have stayed with Carapaz and been racing for gold.

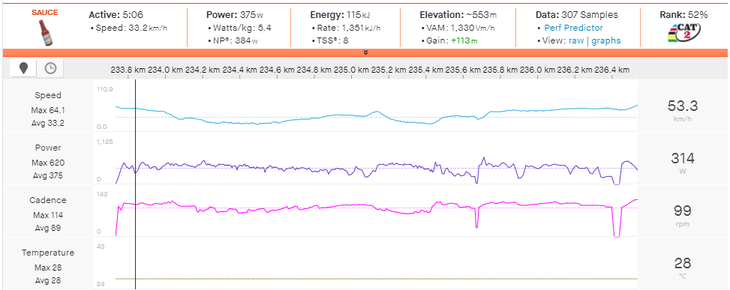

McNulty – uncategorized climb with 5km to go:

Time: 5:06

Average Power: 375w (5.4w/kg)

Normalized Power: 384w (5.6w/kg)

In the final 20km, Woods tried and tried again to bridge across to the leading duo. At times, the gap was as small as 15 or 20 seconds. It was a gap that seemed bridgeable, especially for the strongest riders in the world. After the gap went out to 50 seconds, van Aert brought it back again, all the way down to 13 seconds with 10km to go. But still, no one could make it across, even Woods who attacked on the same ramp that cracked McNulty.

Woods – attacking with 5km to go:

Time: 2:28

Average Power: 413w (6.6w/kg)

Peak 30-sec Power: 626w (10w/kg)

Even after he cracked, McNulty found it within himself to latch onto the lead group as they came flying past. Van Aert drove on the front, while McNulty clung to the wheels until the final sprint. The last 500m turned into a track sprint, with the silver and bronze medals still on the line. Van Aert led it out, David Gaudu (France) launched first, McNulty snapped onto his wheel, while van Aert and Pogačar opened their sprints on the left-hand side of the road. As the world predicted, van Aert was the quickest of the bunch, beating Pogačar with a bike throw for the silver medal. McNulty faded in the second half of the sprint, coming across the line in 6th place, one spot behind Woods who sprinted to 5th. With no regrets, McNulty rode to one of the best results of his entire career. And a time trial with a hilly parcours coming up later this week, we wouldn’t be surprised to see the American challenging for an Olympic medal.

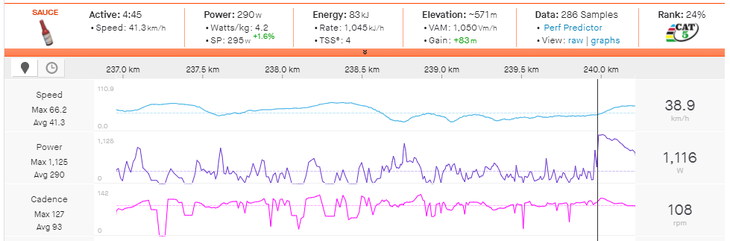

McNulty – final 3km and sprint:

Time: 4:45

Average Power: 290w (4.2w/kg)

Final Sprint: 16 seconds at 934w (13.5w/kg)

Max Power: 1,125w (16.3w/kg)

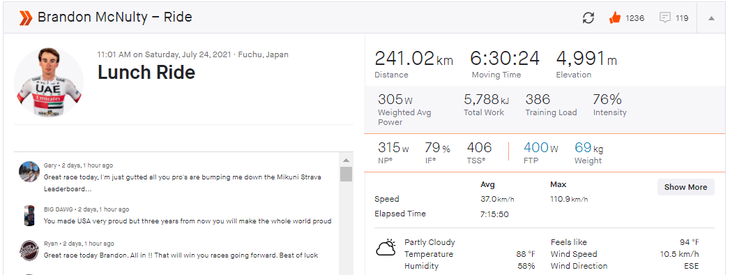

McNulty – Olympic road race (excluding neutral zone):

Time: 6:15:35

Average Power: 255w (3.7w/kg)

Normalized Power: 319w (4.6w/kg)

Max Power: 1,125w (16.3w/kg)

Elevation Gain: 4,801m (15,751ft)

Work: 5,749kJs

Peak 5-min Power: 439w (6.4w/kg)

Peak 20-min Power: 413w (6w/kg)

Peak 60-min Normalized Power: 386w (5.6w/kg)

***

Power analysis data courtesy of Strava and Strava sauce extension

Riders:

Brandon McNulty