Rapha Roadmap, chapter 3: Could teams adopt a franchise model?

Photo: Tim de Waele/Getty Images (File).

As in all sports, it is the teams and athletes themselves that are cycling’s lifeblood. Whether in heroic solo battles, when riders overcome both themselves and the odds to etch their names into the annals of the sport, or season-long domination by one team or another, cycling’s past is always pegged against the individuals who make up each race and each era. In this chapter of The Rapha Roadmap, the research considers how to continue and build upon that legacy. Do you have any feedback or opinions on this story? Please send us your thoughts at roadmapreport@velonews.com.

Beyond the structure of the professional cycling calendar, the format of the races and the crowning of champions, professional teams themselves hold huge power to grow the sport in the 21st century. But to date, evolution of the WorldTour team structure has been limited. While there are examples of successful outreach initiatives, an overwhelming focus on traditional models of performance and ensuring (particularly title) sponsors’ return on investment has too often had a negative effect on fan engagement. There are several reasons for this. The economic model of cycling teams, with near-total reliance on a sole sponsor for funding, shifts focus away from the broader fanbase of the sport and channels resources towards somewhat myopic ‘activation’ strategies. Short-term sponsorship deals, on which all WorldTour teams rely for existence, are regularly cited as the single biggest barrier to executing strategies for sustained audience engagement. The prevalence of teams focused solely on performance is also a problem.

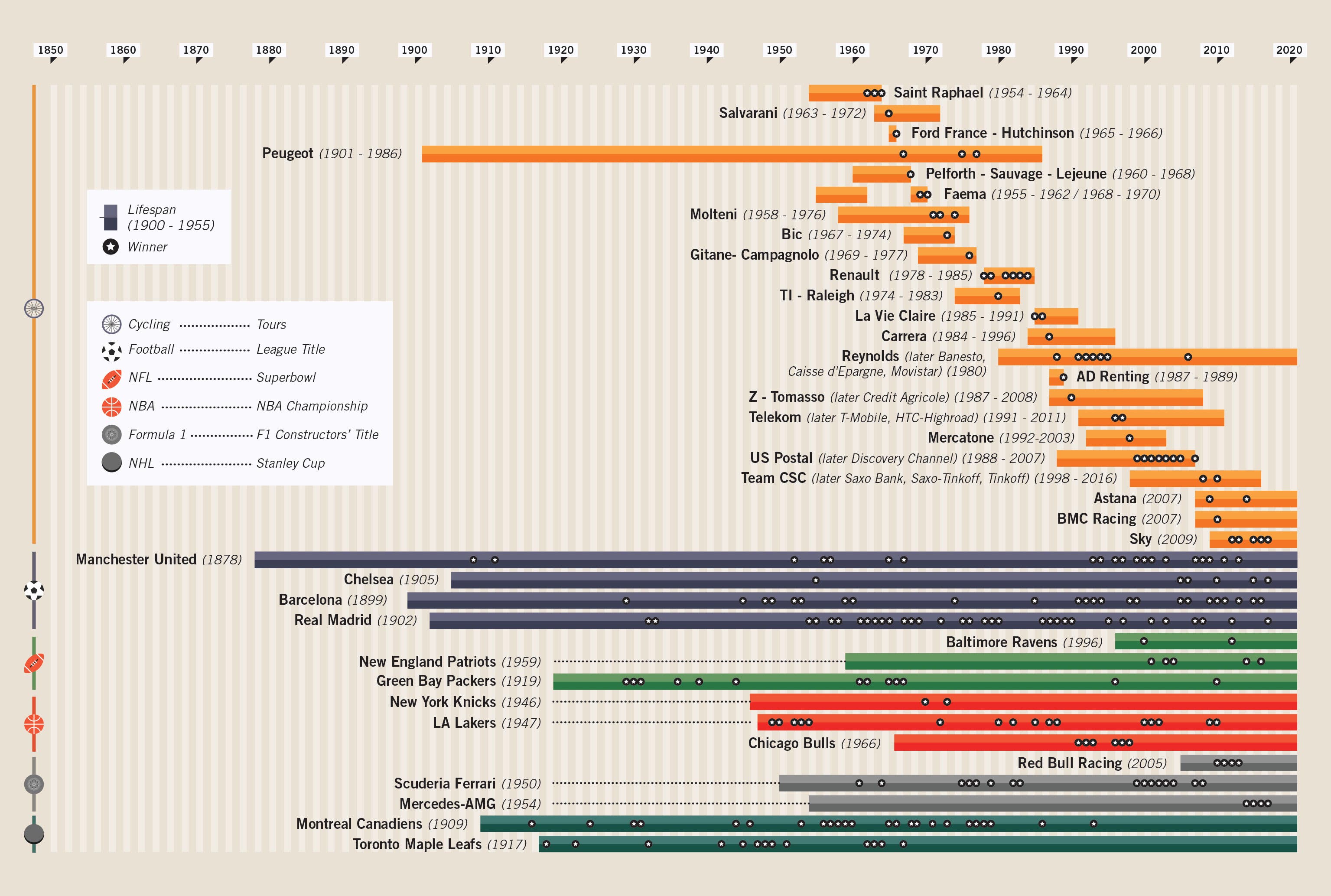

These teams, who judge their success on results at one of half a dozen events in the calendar, create a “feast or famine” culture within the sport, where efforts are directed intensely at preparation around and execution at these moments. Consistent fan engagement, aimed at building predictable habits in their audience with the potential to be monetized, is sacrificed as resources are invested into these single moments of success or failure. The result of these phenomena has been teams with strikingly short lifespans compared to most other major sports and regardless of performance, compounding problems with engagement by creating within the audience an expectation that teams will not endure long enough to make fan loyalty worthwhile.

Where growth has been achieved, it has regularly proved unsustainable. Team budgets for top teams have increased since the 1980s at a yearly rate of about 10%, in line with many other sports, but that growth has proved economically feasible only if the sport grows at the same rate. Cycling has not experienced the worldwide growth secured by other sports, and since team budgets mainly cover rider salaries, this means a sponsor has to pay, on average, 10% more on sponsorship each year for a sport that is not offering any greater return on investment. The sport, as a result of this and broader presentational problems around doping, runs the risk of becoming less attractive to investors every year despite being a sport with a relatively cheap cost per impression.

Overlapping events, and events which are too close in proximity to each other, create further difficulties for WorldTour teams. They are regularly forced to hire duplicate services and carry the inventory costs of redundant equipment to ensure they are covered for busy periods of the calendar. Team sizes have had to expand so that riders can be fielded in all WorldTour races; team staff has likewise swelled to support the increased number of riders in line with CIRC-related requirements of support staff/rider ratios. Multiple team vehicles must be maintained to transport staff and equipment to each race. Additionally, the medical and oversight requirements have added to the administrative investments, putting even further economic strain on teams. These financial burdens may be impossible to avoid in the future, but their impact could be mitigated if the calendar is reformed, if alternate revenue streams are sought for teams and if teams were orientated to focus more on growing the sport’s potential market, offsetting rising costs by creating more meaningful engagement with fans and seeking ways to monetize that engagement.

In seeking potential solutions to these challenges, research for this document suggests future reform of professional cycling teams must be focused on creating structures within the organization that 1) help to make the riders in the team appear more entertaining, developing engaging characters and personalities and seeking new ways to present them to the public, 2) better connect fans to those personalities in person and online, including a regular schedule of fan-interaction opportunities as well as the racing calendar, 3) give riders a stronger voice in their own progression through the sport and its wider organization and structure, empowering them to plan and broadcast their own career 4) reduce the reliance on sponsorship as a revenue stream by seeking alternate income models such as monetized content, interaction and better merchandising, and 5) promote values of equality and diversity, seeking to connect in a more significant way with the community of riders who see cycling as an activity and pursuit rather than a sport.

Professional teams should ultimately be encouraged to favor engagement as highly as performance to increase the media value of the sport, ensuring riders are linked to amateurs and fans as regularly as possible. There are numerous examples of how this can be achieved and many of the interviewees for this research said they were already committed to exploring some or all. Teams should, for example, be encouraged to introduce minimum requirements for riders’ media engagement and participation in public rides should be part of a rider’s contract with a team. Team affiliated clubs should be formed to connect teams to grassroots cycling, along with home-turf races and events hosted and presented by local teams. As it stands, there is a basic failure within professional cycling to create world-renowned athletes who can promote the sport to a broader audience than that which currently watches WorldTour racing. The legacy of the sport’s troubled history with doping and its general failure to innovate its media offering (discussed in greater details below), has been a consistent failure to find and promote the sport’s most compelling characters. If the sport is to thrive in the 21st century, this has to be overcome. To make the most fundamental difference, access to the WorldTour should therefore be restricted to teams who can demonstrate commitment to fan engagement, riders should be recruited based equally on their ability to promote the best values of the sport and their prowess on the bike and they should work to make communities out of their fans, rewarding their loyalty with more and more access and welcoming new viewers to the sport. The creation of engaging and regular content around the sport is vital and teams and athletes are now uniquely well placed to introduce systems that make compelling media and access part of the basic offering of professional cycling. In doing so, they could create new revenue opportunities, including media partnerships, content sponsorship, and monetized platforms. Performance remains a major driver in fan acquisition and loyalty but more could be invested in the promotion of successful riders within the sport.

Where possible, it may therefore be preferable for teams to be rooted in a physical location, where riders could train or live together and where established communities could be linked to the team more easily. Taking steps toward a more nationally or regionally based model, helping to reinforce fan loyalty to their “local” teams, and setting the stage for longer-term regional investor relationships. Today, most fans tend to follow individual racers, even as they jump from one team to another over the course of their careers, and as teams and sponsors enter and leave the sport. Fan club websites and Facebook pages exist for each of the current WorldTour teams, but there is considerably more engagement in fan club websites and Facebook pages dedicated to individual riders on these WorldTour teams, and many other Pro Continental and Continental squads as well. For example, Philippe Gilbert has ridden for four WorldTour teams in his career (Francaise des Jeux, Omega Pharma/Lotto, BMC, and QuickStep), and his fan club has essentially rebranded itself to support whichever team he is racing for, rather than remain fans of his former teams. A new league model could encourage broader geographic distribution for at least some of its teams in a bid to build more teams with a regional or national identity, in order to connect with new audiences in those localities.

It is important to acknowledge that any regionalization of existing teams will be somewhat artificial, especially for those that are already successful and well-known around the world. But that process, despite its obvious pitfalls, may still be preferable to making no concerted efforts to bring elite cycling into local communities. In the past, regionalized support of teams has been hard to see in professional cycling. Stable and long-lived teams, rooted in a particular area, would allow riders to compete on a single team for a longer duration. Instead of following individual racers, this would allow fans to build more enduring team loyalties — as is the case in other team sports. More stability on the roster, and a more clearly visible regional team identity, could increase the level of fan awareness and reinforce regional pride, driving greater overall public interest in the sport as local rivalries develop and mature. This momentum could, in turn, build valuation for broadcast and advertising rights, and grow overall revenue. There is an argument that future reform of the sport as a whole should include a compulsion for WorldTour teams to have a regional base.

Regional teams: Lessons from North America

Studies of U.S. major league sports — Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Basketball League, and National Hockey League — support the idea that regional fan loyalty plays a large role in the success and failure of a sports team. The formula is this: fan interest combined with an uptick in results equals a better economic standing for the team through better ticket sales, merchandise revenue, and an increase in media rights value. The leagues’ governing bodies and team owners assess potential locations for their franchises, basing their decisions on the size of a city’s media market, local competition, and stadium funding agreements with local government.

There is little evidence to suggest that relocated teams retain significant support from fans in their former hometowns — if anything, the opposite is true — however, teams can earn new fans with a well-managed move that is underpinned by a strong economic base and local media coverage. The move of the Seattle Sonics basketball team to Oklahoma City is an archetypal example of this: The move created much animus in Seattle, but the Oklahoma City Thunder proved adept at creating loyalty and community among fans in an otherwise underserved market.

Where regionalization is impossible, the loyalty garnered by local identity could be substituted for loyalty earned with commitment to a single, well-broadcast, and rigorously-tested purpose for the team. “Single-issue” teams, known as much for their mission statement as their performance, have already been seen in professional cycling. Teams like Orica-Scott in Australia, Dimension Data in South Africa or Euskatel Euskadi in Spain, where regional affinity has been superseded by a global appeal born from the teams’ conduct and purpose, have already demonstrated the potential of this approach. Dimension Data was able to create an air of authenticity through their commitment to a charitable cause, providing a rallying point for fans and sponsors which helps to anchor marketing activation for uniquely African products and provides affiliated sponsors with access to an easily activated target market. For example, Deloitte Consulting’s partnership with Dimension Data is providing that firm with valuable marketing presence on the African continent — one of the fastest growing consulting markets in the world. Similarly, brands which co-sponsor LottoNL and Orica capitalize on similar opportunities to reach target markets in the Benelux region and Australasian regions, respectively. Their focus on issues beyond performance builds sustainability, when managed in a responsible and professional manner, building the connection with fans who take emotional ownership: “this is my team.”

There are further opportunities for radical innovation in teams to increase opportunities to engage new fans. Historically, there has been very little encouragement of multi-disciplined riding and genders have been kept separate. Both of these trends should be challenged. Rather than erecting barriers between the different disciplines of the sport by sticking rigorously to road races and designing events in isolation from other styles of cycling, teams and athletes should reach further into a variety of racing styles. The most engaging athletes in professional cycling are almost all multi-disciplined, competing regularly in cyclocross, mountain biking, and other events. In doing so, they have a far greater potential fan base and the opportunity to promote road cycling to unfamiliar audiences. Teams have for the most part done little to capitalize on that potential, regularly prioritizing the team’s road scheduling over a varied and exciting individual calendar. There is, therefore, an opportunity to create a different team model that makes a collective of these athletes from across disciplines and allows each to develop an audience that transcends the boundaries of the road racing community.

Beyond the occasional experiment, there has been a similar reluctance within the WorldTour to develop men’s and women’s squads within the same team. Team Sunweb and Movistar have challenged that trend, with the former launching a women’s team in 2017 and the latter committing to do the same for the 2018 season. Mitchelton Scott, Lotto-Soudal, FDJ, and Trek have also made similar commitments to women’s teams during and prior to the 2018 season. There are competing theories as to how successful this model will be for the teams and athletes involved, and questions as to whether coupling men’s and women’s squads will grow their relative areas of the sport in any meaningful way. There is at least a clear opportunity for collaboration and the sharing of best practice. Canyon-SRAM, for example, has developed and executed one of the most successful models of social media engagement anywhere in professional cycling and the internal structures in place could be adopted in the men’s peloton with ease to boost athlete profiles across the sport. The team has also embraced social media’s power to drive community engagement, driving participation in Rapha Women’s 100 rides around the world. Likewise, the “single issue” team model has not been explored within the women’s sport and the introduction of practices developed at Dimension Data or Orica Scott in recent years could introduce another access point in the women’s side of the sport.

Consider the franchise

Professional cycling’s competitive structure — how teams are organized to compete with one another — must also be revised and modernized. Many of the sport’s economic risks could be eliminated if there was greater confidence that individual teams would be sustainable over the longer term. Economic stability could improve, sponsor interest could grow and stabilize, and teams could know that they had a guaranteed place on the starting line of every top race if the structure and economics of cycling teams were reimagined. Other sports offer numerous models for greater structural stability and cycling could learn from the economic engine which drives almost every other major team-sport league.

There is an argument regularly offered that professional cycling should be franchised in the manner of a modern sports league, and adopt a new competitive structure to encourage competition for team and event licenses. It could easily follow the above recommendation of a top and second division of approximately 15 teams each, with licenses awarded on fixed-term or rolling contracts around the world to incorporate sponsorship opportunities along with other revenue streams to create a pooled income to stabilize the competitive model.

Currently, the 37 events in the WorldTour put a huge strain on the capacities and the endurance of the 18 teams, which are expected to field a competitive squad at each event. With rosters now typically comprised of 25 to 30 riders, teams expected to field up to eight riders in an event, and with so many overlapping races, the teams are often overwhelmed. The logistical and administrative challenges, the shortage of qualified team leadership personnel, and simple athlete exhaustion can lead to situations where the whole sport starts to break down. A franchise model within professional cycling, guaranteeing participation in the most prestigious races and exchanging broader league support for certain commitments from the team, has been proposed in the past as a potential solution to those challenges. A franchise structure could also more easily facilitate a system of relegation and promotion similar to other franchised league models, wherein a lower-performing team might be dropped to the second-division in favor of up-and-coming or new teams. Any such franchise system would need to follow either an American or European structure. In America, lower-tier teams are only able to join if they ‘buy’ a franchise that becomes available or if the number of franchises is expanded. The European structure favors promotion and relegation, based for the most part on performance. Franchises have obvious fan appeal and would help regulate performance in the sport. Races in a franchised league could typically invite approximately 20 teams, thus allowing five second-division teams the opportunity to compete in top races as invited wildcard entries. In turn, this would provide valuable experience and points-scoring opportunities to trigger possible divisional promotion.

Depending upon the sport’s market growth and the supply of top-level professional talent, it might be possible for the number of franchised top division teams to then increase, just as there have been “expansion teams” in other professional sports leagues in a bid to broaden the sport’s geographic footprint. A second division could also benefit from some elements of a franchise structure: a competitive system by which aspiring new teams could enter the system and replace bottom-end franchises which were not performing strongly enough. This would allow another route for new teams to work their way into the league, doing so would also help to establish a clear talent pathway into the sport, something which is lacking in road cycling. The development of a more “sequential” type of calendar could equally raise the value of lower-level events, invigorate the competitive environment for athletes and teams, and thereby increase the incentive for broadcasters to televise a more diverse selection of events.

In this model, each team could be capped at 20 riders, implying a top league with about 300 riders as opposed to today’s WorldTour contingent of close to 500 pro riders. Teams could be expected to enter their top riders in as many of the calendar events as possible, helping to build greater fan interest in the sport through continuity of key athletes from race to race. There could be fewer spots available at the top level of bike racing, but those spots — for both teams and for riders — would be much more prestigious, and together with the other changes proposed here, would enable team franchise values, event income and rider salaries to increase. Renewed emphasis on developing the second-tier teams and supporting races would also help to diversify the excitement level and reach of the sport, while preserving much of its heritage by giving fans a narrative that extends beyond one level of performance or one season of the sport.

A new league could also provide an opportunity to put greater emphasis on rider safety, including the potential for franchise restrictions on racing conduct, including a reduced peloton size with fewer riders per team in all events and the expectation of increased investment by organizers in security. Other specific rider safety improvements could include stricter race neutralization and bad weather protocols (or stricter application of WorldTour-level protocols); the appointment of more experienced safety managers at events independent of the UCI and the race organizers to monitor and ensure required safety standards and regulations; race marshalling by more highly-trained and skilled personnel, and higher minimum experience requirements for both race automobile and motorcycle riders.

And yet, there remain almost insurmountable objections to adopting a franchise model in professional cycling. There are few comparable international models from which to learn, with the majority of examples around the world limited to domestic leagues, and there has been considerable resistance from cycling’s biggest stakeholders. Formula One is one example of an international franchise, proving it is possible to build a sustainable, profitable league structure in sports that transcend borders. Organizers, governance officials and team owners have all said a franchised league could not be created; the revenue streams are too small, the organization too fractured and the incentives too few. When a franchise system is running, however, the opposite is likely to be the case – revenue streams would become more valuable, organizational structure would become stronger and as a result, incentives would be created. Stakeholders have confused the goals of a franchise system with the prerequisites needed to create one.