Rapha Roadmap, chapter 6: How to make it easier to watch cycling on TV

Photo: Tim de Waele/Getty Images

Outside of its traditional markets, cycling is almost impossible to find on terrestrial or subscription television, and a lack of reliable, affordable, and legal streaming services disconnects the sport from its existing and potential markets. Fractured broadcast rights make it almost impossible to view an entire season of racing in one subscription, and the cost across several subscription packages can reach $600 or more. But what if we could sign up for a coordinated, season-long package of major race events for, say, $100 a year, or $200 a year? It shouldn’t be that hard — other sports do it all the time.

The content cycling delivers should be as diverse as its audience, and more authentic and trustworthy. Women’s racing is the fastest growing viewership segment in the sport, but only when it is available to cycling’s fans. More investment into cleaning up the sport’s reputation and association with doping and cheating could help rehabilitate the sport’s overall image. In this chapter of the Rapha Roadmap report, we discuss a wide range of ideas that could help make the production and distribution of cycling content more user-friendly, make the sport more inclusive and emotionally accessible to more fans, and in the process, help grow the sport’s visibility. Please send us your thoughts at roadmapreport@velonews.com.

Professional cycling needs to do more than just develop and produce more compelling television broadcast coverage. It also needs to explore and embrace new approaches and technologies for promoting and distributing that improved content, and combine those approaches with new attitudes to the types of content that are produced.

Most of the WorldTour races are televised in some manner. Monuments and grand tours are often televised around the world, depending on the licensing rights which various national networks can acquire. For example, the Tour de France is broadcast in almost every region of the world. On the other hand, Milano-Sanremo and other similar one-day races aren’t universally available, but can be seen on most European cable and satellite broadcasts. Newer races, like the Tour of Poland and other emerging WorldTour events, are often only broadcast live in their own country, available as condensed productions for the web, and often only via the race organizer’s own website. Meanwhile, entertainment delivery outside cycling is rapidly shifting from bundled subscription packages and traditional television broadcasting to on-demand, internet streaming of single showings and multi-use season pass models that are available across continents and with regional presentations. These new technological opportunities have been exploited to great success by other sports, creating a sophisticated consumer who expects similar variety in other sports distribution. Professional cycling’s stakeholders must listen and learn — and move the sport in similar directions, decreasing reliance on traditional TV rights licensing, and maximizing the opportunities to connect directly with new audiences.

In relation to other professional sports and sports entertainment, cycling has been slow to update its visual product or how it is offered to fans. Cycling needs to move toward the emerging over-the-top (OTT) broadcast model in order to continue connecting with new fans and build a stronger economy. In broadcast, OTT content is audio, video or other media delivered on the internet without the need to subscribe to a traditional cable, terrestrial or satellite TV service. Service delivery partnerships are the key to hitting the market faster, as no race organizer has the roughly $1 billion on hand to build or buy a robust, live-sports capable OTT platform. The new Olympic Channel, quietly launched online by the IOC with technology partnerships at the end of the Rio Games, may be the prototype of this future state. The IOC could increase the webstream license premiums for its broadcast partners, which would increase its overall revenues, or just stream its Games and take the revenues directly.

UFC and the fight for over-the-top

Major sports entertainment brands like the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) still cooperate with cable and satellite television providers to deliver content like pay-per-view (PPV) events, but increased subscriptions to its “Fight Pass” OTT streaming service for specialty programs like exclusive events, content, and replays has multiplied the brand’s profitability.

The UFC has innovated in broadcasting and business strategy to expand revenues. The cable and satellite content has a low entry cost for consumers, allowing people to tune in to watch shows like “The Ultimate Fighter” as part of their normal subscription package, but once the consumer is drawn into the narrative, there is a higher likelihood they will purchase future value-added programming like PPV events and championship matches. The UFC has built its revenues to $4 billion since adopting this format.

Research predicts that worldwide OTT revenue will reach $65 billion in 2021 — double that of 2015 ($29 billion). Many traditional cable/satellite service providers now have more internet connections than cable subscribers, and they are racing to acquire content libraries and customers. From a broader business perspective, OTT technology is also the driving force behind huge mergers in technology and entertainment. For example, AT&T purchased DirecTV to acquire the huge subscriber base of DirecTV’s satellite TV business and is converting these customers to AT&T’s online content platform. It then recently bid $85 billion for Time-Warner, aiming to acquire that company’s vast content library. These moves will help AT&T retain and grow its customer base, market new content as it is produced, target advertisements to those customers, and sell value-added services and technology to maximize what each customer spends. Disney, owner of sports entertainment network ESPN, also acquired a $1 billion stake in a live streaming content distribution company which may soon allow it to bypass its cable/satellite distribution partners in the wake of massive cable viewership losses. Simply put, content is now driving the media value chain, and OTT is driving the business. There are significant growth opportunities afforded by these developments that cycling should seek to exploit.

Adoption of OTT would allow cycling to offer a small number of content licenses to an elite pool of competitive bidders, thus maximizing the value of its broadcast content rights. A smaller number of licensed cable/satellite and OTT broadcast partners, but with a larger overall distribution footprint and more advanced technology, would allow cycling to command a higher overall content valuation than all of the individual races combined today. Traditional cycling hotspots like France, Belgium, and the Netherlands would continue to receive coverage of the major races as they have historically but could be complemented with new and additional content. More importantly, racing fans in other parts of the world could be presented with an unheard-of value proposition: sign up once, choose your preferred level of service, and enjoy a full season of professional bike racing.

This kind of distribution model, with legitimate broadcast licensing and subscription tiers, provides the opportunity for the sport to collect “gate” revenue from the fans. And the improved consumer data from online sign-ups would help spur much more innovative and lucrative marketing strategies. Delivery of cycling’s most valuable content by OTT can also help drive the sport’s overall future growth. Even though the majority of professional cycling’s viewership takes place for free, diehard fans outside of its traditional markets have the proven financial means, access to technology, and emotional connection to the sport to pay a premium to see exactly the races they want, and in the format that is easiest for them. How the sport connects with and values that growing and affluent fan base will have a big impact on professional cycling’s profitability in the future.

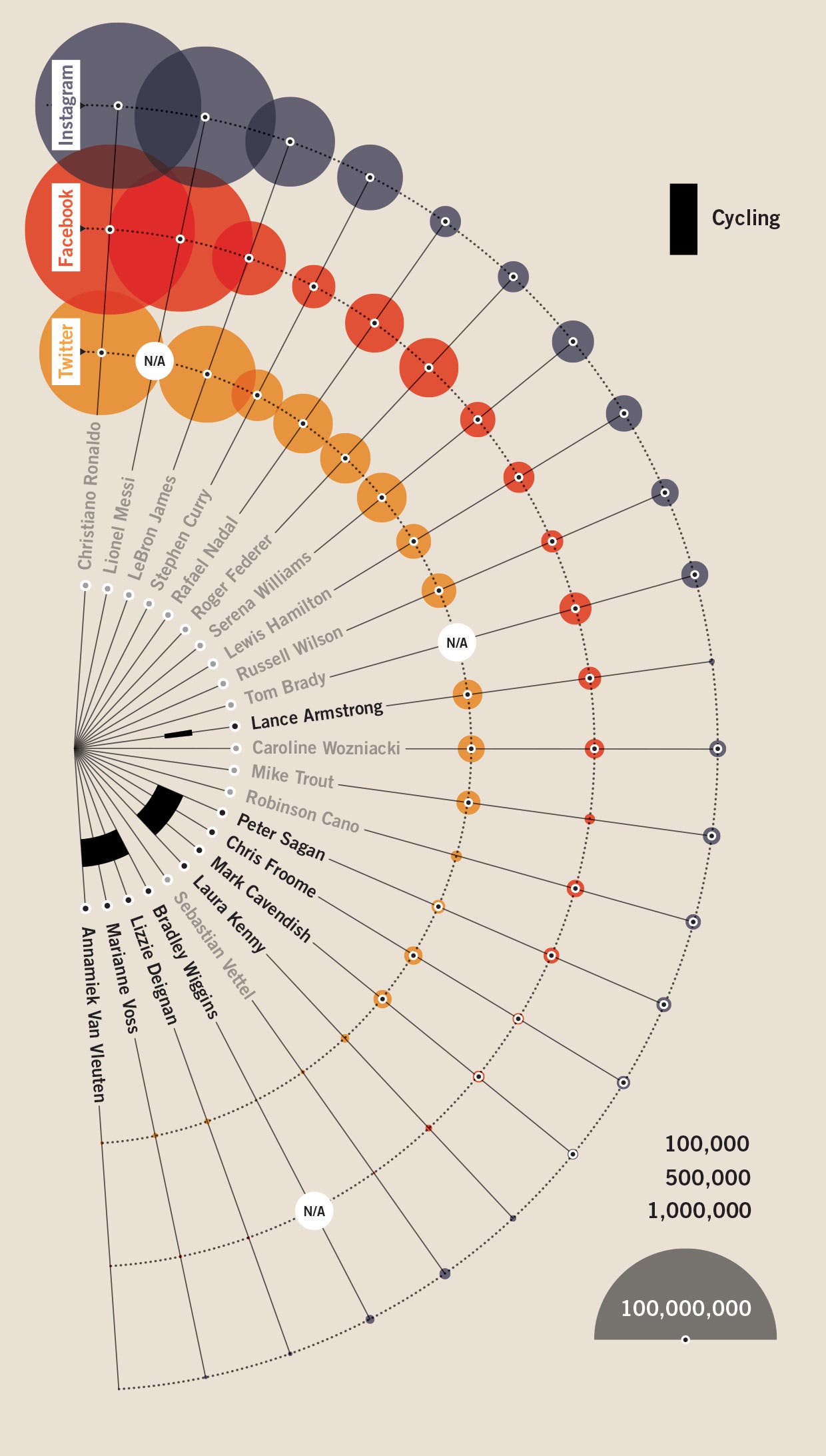

If properly managed, packaged and marketed, a new league model and calendar could be an ideal vehicle for promoting a new season-long broadcast product. That offering could be licensed as a consistent and uniform programming package or entice high uptake of an online subscription product. For the frustrated cycling fan accustomed to tapping into choppy and often legally blocked video streaming sites on foreign-language websites, the ability to purchase a season-long package comprising all of the races over the internet or a single cable TV channel could hold considerable appeal. Interview research for this work unearthed several further opportunities for episodic, made-for-mobile content with reduced rights fees and enhanced access. Riders, teams, major event organizers, and governing bodies all expressed their desire to facilitate better episodic content creation with the sport, finding and promoting the characters within professional cycling that can connect with a new generation of fans. The importance of that regular promotion of an iconic figure within the sport cannot be overstated. According to senior figures within USA cycling, Lance Armstrong’s personal rise to the top of the sport facilitated a massive, continent-wide growth in road cycling participation. It has been claimed his downfall subsequently led to a dramatic and continuing fall in membership of the organization.

A newly-proposed calendar could also justify the creation and negotiation of a totally new set of comprehensive broadcasting rights (discussed below) even though it will be comprised of fewer and more select events. Some other highly successful televised sports have relatively few events or games during a full season, including Formula 1 or American football. Fewer but more significant and higher-quality races, in which all of the top racers participate, could help cycling to develop more of that elusive “scarcity value.” This would constitute a significant economic change that would, in turn, increase the value of sponsorship investment and broadcast revenues.

A final opportunity implied by increasing television revenues is the eventual ability to share that money with the league in order to build the value of individual teams and enable a more competitive, financially sustainable and entertaining sport. From the perspective of the league, this shared revenue would also allow the construction of an incentive system under which the teams could be required to meet certain desired performance and participation criteria in order to share in the pool. The revenues will initially be small, and the general approach will be opposed by those who pocket most revenue and profit of the sport today. However, there are encouraging signs that some race organizers are open to considering different alternatives, and the large organizers must be convinced that a slightly smaller piece of a much bigger pie will be to the benefit of the entire sport. The lesson from other major sports is clear: When television revenues grow and are shared across the teams, this builds financial stability, improves the investment atmosphere, and provides the long-term foundation from which the sport can grow.

To go further, professional cycling should experiment with e-sports and virtual participation. Soccer is just one sport that has experienced an explosion in engagement through the success of EA Sports’ FIFA series and the viral popularity of local teams dramatized online. Cycling should look for what’s next. The technology already exists to integrate live races with home trainers, and companies like Zwift have led the way in connecting indoor workouts with a wider community. The future of the sport may lie in mass online participation, allowing anyone training at home to virtually take part in any live or historic race, or it could be found in the massive successes of e-sports, digitally rebuilding the most iconic roads for new fans across the globe. Arenas are filled by online gamers around the world and their attraction has proven that the live audience for digital sports is growing considerably quicker than their traditional predecessors. Key figures within the e-sports business have explained their desire to build more sophisticated content into alternative platforms, capitalizing on the fitness community already engaged for long periods of time due to the activity on offer. It is understood companies like Zwift will continue to develop content hubs within their platforms and associated with their core offering. These could be seen as a boon or a threat for the traditional sport, depending on perspective. Event organizers and teams should do more to act on the opportunities made available by rapid growth in this area. Two teams, Canyon-SRAM and Dimension Data, have already experimented in this field. Both have offered some form of professional rider contract to talent spotted and tested on the Zwift platform. They have also used their own channels and associated media, such as the Global Cycling Network (GCN), to record and promote the process. Regardless of the performance impact, their willingness to experiment with new forms of talent pathways and innovative outreach should be promoted more widely in the professional peloton.

Netflix and the dramatization of the sport

Cycling’s next phase of broadcast development may come through media partnerships with non-traditional content providers to bring the sport to a younger audience, including digital providers like Netflix, Amazon, Sony, HBO, Vice, and others, as well as exclusivity partnerships for traditional content with free media including YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, Periscope, and others. It could and should move beyond race broadcasting to documentary-style series created for non-cycling audiences, learning from the success of Last Chance U, All or Nothing, Iverson, The Battered Bastards of Baseball, and many more, and new formats for covering live events that are considerably shorter and more mobile friendly. Major over-the-top content creators and distributors have begun experimenting with live sports broadcasting and have cited the success of sporting documentaries as proving a digital OTT audience for sport on non-traditional platforms and channels. It has been rumored that these companies are actively considering bids for major media rights around the most well-known sports properties.

Stop ignoring women

An important and often overlooked way to advance interest in the coverage of cycling — as in so many sports — is to better manage and promote the women’s side of the sport. While it is possible to follow women’s racing, it is very difficult to obtain broadcast coverage and its exposure is still only a fraction of what the men receive. Too often, women’s racing is minimized, diluted, or completely overshadowed by coverage of a parallel men’s event. Only 25% of the Women’s WorldTour could be seen on television as of the 2017 season, and only four races are broadcast live: La Course, Tour of Flanders, Women’s Tour of Great Britain, and the RideLondon Classique at the time of writing. (Coverage expanded in the 2018 season). That has a major impact on the development of the women’s sport. The relatively tiny fraction of race days available for viewing keeps the audience small and reduces the incentives for sponsors to enter the sport. As a result, the finances of women’s professional cycling are in particularly bad shape. Team budgets are many times smaller than in the men’s sport, events regularly rely on volunteers to ensure they run and it is believed more than half of women riders work a second job to secure a living wage. The typical cost to run a UCI “Elite” professional women’s team is as little as $100,000. An estimated 51.6% of female pro cyclists also have to pay back parts of their salaries to their teams, in order to pay for basic necessities such as equipment, travel costs, and the services of a coach. There has also been a worrying trend for allegations of sexism and bullying in the women’s side of the sport, which with under-investment and regulation threatens to dominate the narrative around women’s racing.

And yet many veteran cycling observers insist that women’s racing is every bit as exciting and dramatic as the men’s and lament the general scarcity of coverage. The quality of media coverage was cited by every female athlete interviewed for this research as amongst the most important factors affecting growth of the sport. There is also evidence that regular broadcasting of women’s racing can help to create an audience for the sport. Flemish TV, for instance, started broadcasting women’s cyclocross competition two hours before the men’s race and after three years, TV ratings have steadily grown to around two-thirds of the men’s ratings. However, stakeholders are divided on how best to pursue enhanced coverage. For some, coupling men’s and women’s racing is the most practical approach, allowing pooled coverage costs and encouraging cross-promotion of the races to dual audiences. For others, there is a significant risk in growing the audience for women’s cycling in the shadow of men’s and a more radical break with tradition is promoted as the best way forward. Whichever approach is favored, there is a general acceptance that major advances have been made in the last decade and there are several examples of compelling content creation around teams and athletes. This has been reflected in the increased individual reach of female riders. However, this has often been as a replacement for traditional coverage rather than to supplement it. There remains a startling resistance to promoting women’s cycling amongst some of the most influential stakeholders in the sport and there is an acceptance within teams that athletes must promote themselves if they are to attract any fans at all. This has had the effect of developing some of the most sophisticated social media strategies in professional cycling, but their effect in growing the total audience for the sport has been lamentably small. Many believed the sport is missing a major opportunity in not pursuing broader promotion of women’s racing on a similar scale to the men’s.

Research into gender splits in purchasing habits suggests women’s cycling can capitalize on many new and different sponsorship opportunities, rather than relying on the end-market and customer categories which have traditionally driven the men’s sport. There is a unique opportunity here for the right companies to capture the attention of a sports viewing population — a more educated and higher-income female audience that either spends money, or influences the way in which money is spent. There is some preliminary evidence that there is a significant potential audience for episodic content about the women’s sport with targeted sponsorship. The Cycling Podcast’s regular Feminin episodes average around 60,000 plays, just marginally fewer than the core show, and its audience has grown to almost 12% in the past 12 months. There is also the opportunity to deepen relationships with spinning and other online fitness communities, which could provide the incentive for women to participate in all manner of virtual cycling activities.

Existing races and events in our proposed calendar could capitalize on related or parallel women’s events, driving new revenues that would be unique and separate from cycling’s traditional models. Models are already there in other women’s sports, from which cycling can learn. The growth in women’s tennis, for example, led to the creation of many new tournaments and series which became self-sustaining, marketable, and highly profitable. Many of those involved in women’s cycling have recommended a less disruptive approach in the presentation of their sport as distinct from men’s racing, but given the animosity in some areas between riders and organizers, a similar split may be inevitable. The ability of women athletes to transcend their sports or to connect in a meaningful way with women who enjoy the sport is something which professional cycling must facilitate. Reform of women’s cycling has the potential to outshine men’s and change the sport’s business model in the process. Greater visibility of the women’s sport, more focus on the individual athletes and their personal stories, and increased investment in women-specific products and forums could attract many new participants, and foster long-term growth in cycling overall.

Tennis and the battle of the sexes

The rise of women’s earning power in golf and tennis demonstrates how athletes’ earnings and marketability benefit the sport as a whole. In tennis, parity between men and women has developed in a piecemeal fashion since the infamous ‘battle of the sexes’ between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King in 1973. King’s victory fostered a change in perception of women’s tennis, and this was matched by a gradual movement to equal pay for women — the U.S. Open awarded equal pay from that year, and the other Grand Slams edged towards near-equal pay from that moment on. The impact of equal pay is diffuse, and is arguably more important for the women lower down the rankings. The example highlighted in issue six of Mondial magazine is Agnieszka Radwanska, ranked tenth in the world, who has earned more than £13 million in her career yet has never won a Grand Slam. By creating a system in which women, like men, have viable careers without needing to be once-in-a-generation talents, the overall level of competition improves, and talent is allowed to develop over time by reducing the need for overnight success. Women’s cycling, unlike tennis, has not experienced a steady journey to parity. The high water mark for women’s cycling was the mid-80s, when most major races in the U.S. had a women’s counterpart (a rarity today), and sizable prize purses meant strong fields. As in tennis, the strongest moves towards equality from women’s cycling haven’t come from a top-down approach by the sport’s governing body, but measures taken by race organizers and team owners — see the award of equal prize money at several of the U.S.’s largest cyclocross races, or the recent success of the women’s Tour of Britain.

Raising the profile of women’s racing should go hand in hand with efforts to end the use of “podium girls” during award ceremonies. Professional cycling should follow the example of Formula 1 and professional darts and end the use of women as promotional tools, a move that started to be adopted at some of the largest races in the 2018 season. The practice of scantily-clad females presenting podium winners with champagne, flowers and cuddly toys is regularly derided as outdated and has no place in modern sport. This is demonstrated by the scandal that erupted after Peter Sagan made a pinching gesture towards the backside of a podium girl in the 2013 Tour of Flanders and similar outrage at a poster for E3 Harelbeke the following year, which appeared to reference the Sagan episode. Nevertheless, shocking moments of careless sexism continue. During last year’s Tour de France, Belgian rider Jan Bakelants said by way of a joke that he would be taking “a packet of condoms as you never know where those podium hostesses hang out.” As of publication, the UCI has announced no blanket plans to end the tradition of podium girls although the Tour Down Under ended them last year and the Tour de Yorkshire prefers to celebrate local businesswomen. Some women have spoken out against a ban on ring girls and flag girls. They claim the work is well paid and a ban would affect women’s employment opportunities. One female MMA fighter went so far as to say the Octagon girls were paid more than her.

Tackle the reputation

A powerful opportunity for attracting broader audiences is to make professional cycling more trustworthy by improving its public perception and reputation. Fairly or unfairly, much of the broader population views professional cycling as a “dirty” sport — one that is widely populated by dopers and cheaters. There is a fundamental problem with the narrative around professional cycling in its most developed geographies, as alluded to above. Coverage of cycling in the non-endemic media is dominated by two types of content. First, when considering the activity of riding, content is overwhelmingly focused on safety and issues associated with shared road usage. The ongoing battle between road users and the collateral damage it inflicts dominates the public’s conception of cycling as a means of transportation. For many experts, this represents the single largest barrier to a significant increase in cycling participation. The issue, and the ways by which road cycling can tackle perceptions of safety, is substantial enough to warrant its own body of research and is beyond the broader scope of this work. Second, when considering the elite sport, coverage dramatically increases when focused on doping and related rule violations. Professional cycling has had a near fatal reputational problem as a result of decades of doping scandals. If the sport is to grow with any sustainability, it must tackle this problem. It is debatable whether this reputation is warranted. Professional cycling has done more than most other professional sports in recent years in attempting to understand and eradicate doping problems. Senior figures throughout the sport continue to claim that professional cycling is the cleanest it has ever been. Nonetheless, the image still exists in the minds of many less informed casual or non-fans that the sport is dirty and it is quietly acknowledged within the professional peloton that teams continue to push at the limits of permissible methods for improving performance, using every conceivable advantage with manageable risks of a rule violation. Suspicions often fall on the bikes as well, with many convinced of the widespread use of mechanical doping, or technical fraud. Bikes are already subject to thorough tests around professional races but it has done little to dampen speculation.

There remains significant distrust and disagreement amongst the sport’s key stakeholders on how to tackle doping and how the motivation to cheat is born. Past offenders have cited the instability at the heart of professional cycling as a major driving factor. Assuming these is not an a priori motivation among athletes to use performance-enhancing drugs, they claim the packed and overlapping race calendar, commodification of rider performance and economic instability of sponsorship income encourages an atmosphere of urgency and desperation which can result in sporting misconduct. The sport has to squarely face this challenge, if it is to ever win over disaffected fans or connect with new fans.

The timeline of a scandal

The history of doping in cycling is a succession of scandals, each marked by headline-grabbing positive tests, police raids, and fervent denials. Trying to make sense of this murky world is made difficult by the peloton’s culture of omertà — a code of silence borrowed from the mafia — and the lack of reliable accounts can reduce even the most ardent fans to an ambivalent shrug and a lingering, generalized suspicion of all riders.

Many point to the early-90s emergence of Erythropoietin (EPO) and blood doping as the nuclear moment of the doping arms race, partly because of the effect on the peloton’s speed was so noticeable and their use was more or less ubiquitous. But the physiological effectiveness of EPO is only one part of the story. The other is the political and cultural framework that allowed for the prevalence of doping practices.

Throughout the Cold War, state-mandated doping problems touched almost every Olympic sport. These programs were systematic and quasi-scientific, with coaches and doctors working together to achieve a competitive edge for their athletes — although the athletes were often unaware of the substances being administered to them. This culture is markedly distinct from contemporaneous accounts of doping in cycling, in which riders dosed up with stimulants, steroids, and occasionally champagne, but rarely with any systematic vigor.

As road racing became steadily more professionalized through the 1980s, teams became wise to the insurance offered by a carefully considered doping program — ‘prepared’ riders got better results, the thinking went, pleasing sponsors and thereby securing a team’s financial future. As a consequence, the practice of doping became more serious, borrowing ideas and techniques from state-sponsored doping programs. Prominent doctors earned huge sums by designing and administering team-wide programs.

This is the model that operated through the early ‘90s, with Team Telekom being one of the most advanced practitioners, all the way through the Festina Affair and the Armstrong years. This era is also noted for the lack of accountability for teams and riders. The UCI, fearful of tarnishing their product, shied away from going after riders and followed anti-doping policies such as the ‘50% hematocrit’ rule, which were so easily sidestepped they became known as intelligence tests rather than genuine anti-doping efforts — only the most careless of the peloton were caught out. The press corps, whose success depended on genial relations with the peloton and access granted by teams, had little incentive to expose scandal. Long into the 2000s, the only serious investigation into cycling’s doping problems came from national police forces in France and Spain.

It is thought that the team-sponsored system of doping has gradually fallen from favor as the political cost of doping has increased — that is, corporate sponsorships have been lost as a result of doping scandals, and teams can be served sporting punishments if two or more riders test positive in a season — and as Europe’s laws have increasingly cast doping as a criminal matter. The wide-ranging fallout from Operación Puerto, an anti-doping investigation by the Spanish police against a notable Italian ‘dope doctor’, Eufemiano Fuentes, has given rise to a new chapter in the story of doping: solo riders, or small groups of riders and coaches, organize and pay for their own programs, reducing the risks inherent in a team- based system with many people ‘in the know’. Other notable trends are the use of research chemicals in the early stages of medical testing (AICAR and GW1516 are two examples, both of which have poorly understood and potentially disastrous side effects), the use of opioid painkillers during races, and the abuse of Therapeutic Use Exemptions to use otherwise banned drugs with apparent approval from the anti-doping agencies.

A number of recommendations have been suggested in interviews with athletes, teams, organizers, and governors for this research. To start, cycling must devise and implement new monitoring, policing and certification systems to better address its historical doping challenges, building on developments already made in this field by implementing the recommendation made in a series of major anti-doping studies. The ethical training and expectations of competitors and team management personnel must be hardened; safety standards must be raised and financially supported by race organizers; legal medications and the doctors who prescribe them must be more closely regulated; and anti-doping regulations must be strengthened and coordinated across multiple agencies to minimize future impacts to the sport’s reputation. It has also been recommended that the UCI divest itself of all anti-doping policing, given the challenges within the organization, and allow the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) to oversee these activities. Likewise, governors argue that individual teams and events must set tougher standards and testing requirements. The ease with which therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs) can be acquired and their clear potential for misuse should also be addressed with particular urgency. Failure to keep accurate and detailed medical records of legal drug use should be more severely punished.

Beyond regulation, some believe the sport needs more prominent and consistent flag bearers for clean cycling. These figures might be formally recognized and incentivized, associated with specific teams or events, to act in pastoral and outreach capacities to ensure the issue of doping is not left to fester without attention. There may also be further need for a broader discussion about the continued use of drugs in professional cycling. Several of the most recognizable figures in the sport have called for a public process of truth and reconciliation within the sport, in which a kind of amnesty for historical transgressions is exchanged for root and branch examination of doping practices and controls. The facilitation of a prolonged investigation of practices could act as a release valve for the issue, they said. However, significant attempts at a similar process have been attempted in recent years and many stakeholders acknowledged fatigue around the issue within the sport.

Special mention should be made here of doping in the women’s professional peloton. Owing to issues around resources afforded to anti-doping controls in the women’s sport, riders undergo far fewer tests than their male counterparts. Athletes have privately predicted that up to 50% of professional riders could go their whole career without facing anti-doping controls on more than a handful of occasions due to the way riders are selected for tests. The same model, of testing only those with suspicious or consistently strong results, is used for anti-doping control in elite men’s cycling beneath the top levels of the sport. This bifurcated testing model presents a challenge in addressing the reputation of the sport and further compounds the risk of rule violations at every level.