The payout from the 2022 men’s Tour de France reflects the wide range of success and failure at the season’s most important grand tour.

Tour winner Jonas Vingegaard earned a winner’s check worth €500,000 in the biggest paycheck of the men’s WorldTour.

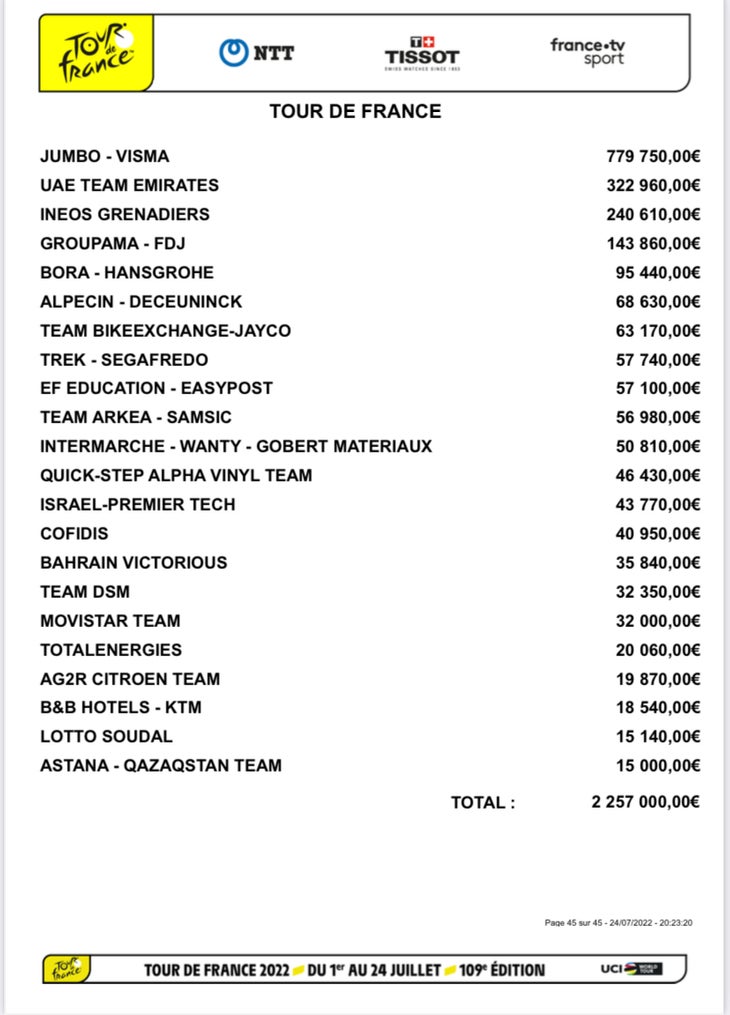

The winner’s checks from the 2022 Tour prize money purse are top-heavy, with the teams of the top-three podium in Paris soaking up the lion’s share Sunday. Teams at the bottom of the barrel barely broke into five figures.

That’s no surprise, of course, since payouts for the final top-three podium finishers and the jersey winners receive the biggest chunks of individual prize money from the Tour’s €2,257,000 total purse.

In fact, the final payout in Paris reflected which teams succeeded and which teams quite literally went home empty-handed at the end of three weeks of racing.

Tour-winner Jumbo-Visma won one-third of the entire pot with €779,750, with Vingegaard in the yellow and King of the Mountains jersey, Wout van Aert in green, and the team winning six stages across the 21 contested from Copenhagen to Paris.

Also read: VeloNews explainer — How the Tour de France prize money works

Vingegaard received the largest individual check for winning the yellow jersey, with this year’s first-place prize at €500,000. With the euro and U.S. dollar at near parity, the conversion is just under one-to-one.

UAE Team Emirates, though second with Tadej Pogačar who also won the white jersey and three stages, brought home less than half €322,960.

Ineos Grenadiers, third with Geraint Thomas and the winner of the team competition, won €240,610. Groupama-FDJ, with David Gaudu hitting fourth, is the only other team hitting six figures on the month, with a haul of €143,860.

In fact, the top-three finishers in Paris on Sunday earned more than a third of all the prize money on offer during the entire Tour.

With only half the teams winning stages, the financial payout dropped from there. Israel-Premier Tech, which won two stages and hit a few more top-5s, brought home €43,770, while BikeExchange-Jayco also won two stages and will cash out with €63,170.

At the bottom of the list were Lotto-Soudal and Astana-Qazaqstan, as neither team won a stage, bringing home €15,140 and €15,000, respectively.

How the prize money is earned and split out

The Tour’s prize money is both transparent and opaque at the same time.

The allotment from the Tour organizers is outlined in the race handbook, and is inline with the UCI’s minimum requirements for prize money.

What remains opaque is how riders earn their wages via salaries across the entire season, and how teams split out of the pot at the end of a race.

The winner of the men’s Tour receives a WorldTour-high payout of €500,000. Tradition holds that the winner forfeits his winner’s prize and splits it out with teammates and staffers.

According to team sources, that tradition still holds true in the modern peloton.

Typically a team will tally up the total prize money pool, so for example, a top Tour team will take their total take and divide it out, most likely by eight. Seven parts go to the riders, and another portion is divided among the staff that includes soigneurs, chefs, mechanics, drivers, and other backroom staff.

Sport directors and mangers do not receive a portion of the prize money, though some top directors, coaches, and trainers might receive a bonus for top results.

A generous winner might offer an additional prize to teammates, be it expensive watches, a paid vacation, or some other significant gift.

During the 2022 Tour, a staffer on a top team like Jumbo-Visma might earn up to a high four-figure Tour bonus, while someone working at Astana-Qazaqstan might not be able to buy a nice dinner with what they will receive.

Pogačar received €200,000 for finishing second, but also won €11,000 per stage victory, with each day’s stage doling out individual prize money for the top-20, with €300 for 20th place each day.

Every rider who arrives in Paris receives at least €1,000 as the minimum prize for surviving three weeks.

Also read: What the top male pros are earning in the WorldTour

Other podium spots bring prizes, with €25,000 for the winners of the major jerseys. There were primes sprinkled across the race, with €5,000 going to the winner of the Tour’s highest point, and cash payouts for intermediate sprints along the way.

Even if a rider or team doesn’t win a stage or a classification, placings can still add up.

In stage 16, for example, Nils Eekhoff (Team DSM) darted ahead of Van Aert to pip him for top points at any intermediate sprint. Van Aert was firmly in green, and Eekhoff had no chance to win the points classification, but it’s a finish line, and he earned €1,500 for the effort.

The day’s most combative prize earns €2,000, so it pays to attack until the very end. The Tour’s most combative prize earns €20,000, plus a trip to the podium.

Ineos Grenadiers won €50,000 for the team prize, and though the peloton’s richest team won’t notice, its backroom staffers certainly will.

Race officials discreetly hold back on sending out prize money checks for a few weeks until all the doping controls have been cleared.

Prize money ‘counts for less’ in today’s peloton

Prize money at the Tour and other top races counts for less as salaries and bonuses in the modern era continue to climb ever higher.

That wasn’t always the case. Before the advent of larger team budgets and million-dollar-salaries, prize money and appearance fees were an integral part of any top pros ability to earn a living.

Cycling is unique in many ways, including how the top WorldTour pros earn money.

Unlike tennis and golf, for example, where athletes earn most of their income from seven-figure prize money checks and sponsorship deals, cycling’s biggest stars earn hefty salaries that can reach well into seven figures. Prize money and special primes is not how the modern pro cyclists brings home the bacon.

Top stars like Peter Sagan and Chris Froome also earn additional income that can also reach millions through sponsorship and partnership arrangements with bike manufacturers, sunglass companies, and other consulting fees. Post-Tour critériums can still earn the top star five-figure paychecks for an evening spin around the block.

Top winners also have individual winner’s bonuses written into their respective team and sponsorship contracts, which can often mean millions more in payouts after a big season.

Cycling’s salaries, even at the top end, remain relatively paltry compared to the very elite of European soccer and top major U.S. team sports, where top salaries can hit $20,000,000 per season and more.

Without stadiums to fill or tickets to sell in cycling, even bench players in the NBA will make more than just about everyone in the Tour peloton.

What’s an “average” salary in the men’s WorldTour?

That depends on a lot of factors, particularly what’s a team’s overall operating budget. Expenditures on coaching, training, nutrition, staffing, and materials has increased dramatically in modern cycling, but the lion’s share of any team’s budget remains rider salaries.

So it’s no surprise that the best-paid riders are on the teams with the deepest pockets.

Also read: UCI president mulls salary caps

A top GC captain and and a handful of classics superstars can earn salaries topping $3 million per year and up. Tadej Pogačar is reportedly cycling’s highest-paid racer right now, with an annual salary estimated to top $6 million per season.

Behind them, there is a deep row of established pros, proven winners in sprints or climbs, super-domestiques, and road captains whose salaries can range from $500,000 to the low seven figures.

At the other end of the spectrum are WorldTour rookies, who see a minimum salary of $36,000, while the middle chunk of any WorldTour team’s roster is filled with ever-steady workers on salaries ranging from $150,000 to $400,000.

Before the advent of cycling’s million-dollar salaries, prize money, primes, critériums and other payouts such as start fees were vitally important to a rider’s income. With the pressure to make as much money as possible with only a short few years to try to earn top dollar, riders could double, triple or even quadruple their sometimes meager salaries.

Also read: Outer Line and how the new rider’s union can succeed

Unfortunately, that pressure to earn money as quickly as possible often led riders and teams to dope or to buy and sell races, something insiders say happens a lot less than a generation or so ago.

Today’s peloton is a cleaner and more sporting place with higher salaries, meaning there is less temptation or rationale to dope or to sell a race because riders are already on big-money contracts.

If a rider is getting paid the same whether or not they dope — unlike in the past when rider’s would actually receive higher salaries if they did agree to dope — and many teams are begging their riders not to cheat, the argument goes that riders have less incentive to dope, and today’s peloton is cleaner than before.

Today’s pros race half the number of race days, or even less, than a top pro a generation ago or so would race. Until the turn of the century, riders would post 90 to 120 race days a year, plus dozens of other critériums and off-season racing on track and cyclocross. In contrast, Pogačar raced 61 days in 2021.

In general, in today’s peloton riders race less and get paid more, and the peloton’s overall health is better off for it.

Riders race less and are paid more than ever before

So that takes us back to the Tour prize money. How much is it, and what does it mean?

Among the WorldTour, the Tour’s payout is the largest by far. The Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a España pay out about half, respectively, to what the Tour shares with the peloton.

Who pays the prize money? The race organizers. They take a chunk of their total operating revenue and dedicate a portion of it to prize money. The UCI and the WorldTour bylaws also have guidelines for prize money minimums at any the major races, and teams also receive direct payments from ASO as well as free hotel rooms across the race.

There’s an ongoing debate about how race organizers such as ASO and RCS Sport how income streams as TV rights and VIP zones and the publicity caravan should be split up more equitably among teams and riders, but as it stands now, the race organizers hold all the revenue chips.

Also read: Women’s salaries remain a fraction of what top males earn

Top male cyclists today earn more money than at any time in professional cycling. They race less and are paid more than any generation before them.

What hasn’t changed is that there is still not a lot of job insecurity, as team sponsors can evaporate in an instant or an injury can spell the end of a career in one bad crash. Most contracts run two to three seasons, with a relatively big chunk riding on one-year contracts, though a few major stars like Egan Bernal or Pogačar are signing five-year deals.

Teams are hunting out younger, cheaper riders, and spending money to develop them in-house with the hope they will discover the next Tom Pidcock or Jonas Vingegaard racing at some third-tier team. The top teams are taking a longer view, and building out their rosters across several years, instead of hiring and firing hired guns.

Major teams now have full-time talent scouts, and sport directors and managers ply Strava and their contacts in the junior ranks and national federations hunting for the next diamond in the rough.

Cycling isn’t producing a lot of millionaires, not on the same level as the top stadium sports, but for the relatively niche sport that it is, sources confirm there are about 35 or so riders on million-dollar-plus annual contracts within the men’s WorldTour. That’s likely one or two per WorldTour team, with big-money squads like Ineos Grenadiers or UAE Team Emirates having up to a half-dozen on their respective payrolls.

Does it pay to be a professional cyclist?

Paychecks are bigger and deeper than ever before. Prize money doesn’t count as much as it used to, but it’s still a nice cherry on the cake at the end of a hard Tour de France.