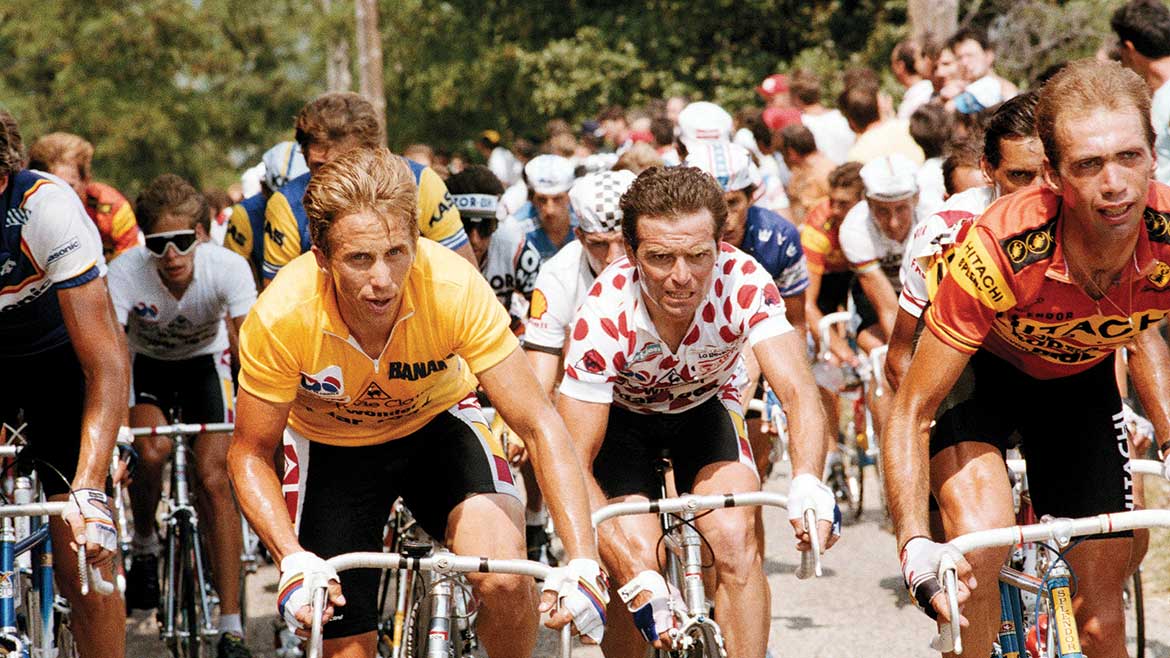

The greatest Tour de France ever

Photo: AP Photo/Lionel Cironneau, courtesy VeloPress

The following is an excerpt from the new foreword to Slaying the Badger: Greg Lemond, Bernard Hinault, and the Greatest Tour de France, by Richard Moore.

When “Slaying the Badger” was first published in the U.K. in 2011, it sparked a bit of a debate about the claim made by the subtitle, “Lemond, Hinault, and the Greatest Ever Tour de France” (changed in the U.S. edition to “Greg Lemond, Bernard Hinault, and the Greatest Tour de France”).

It hadn’t been my intention to be put on the spot about this, or even for it to be much of an issue. Naive, I know. But it seemed beside the point, a needless distraction from the story of the LeMond-Hinault duel. It had only been intended as an eye-catching subtitle.

And yet the discussion proved rather interesting. What was also noteworthy was that, among those who initially objected most strongly, a certain wavering, or uncertainty, could be detected — not because they were convinced by anything I said but because, when they considered other Tours, they realized how difficult it is to settle on one as the definitive greatest ever.

As other possibilities were pondered, some alighted on 1989, when LeMond claimed his second victory, this time on the final day and by the smallest margin of victory ever in the Tour. Another popular one was 2003, when Lance Armstrong overcame adversity — and an in-shape Jan Ullrich [this being before the Reasoned Decision and Armstrong’s doping confession]. Those with a sense of mischief — and an appetite for the drama of a drug scandal — nominated 1998, the year of the Festina Affair, as well as of police raids, rider strikes, and the subplot of a gripping duel between Marco Pantani and Ullrich.

Such choices reminded me a little of those “Greatest Albums of All Time” lists, which are always stacked with recent releases. The cycling equivalent of placing Lady Gaga’s “The Fame” ahead of the Beatles’ “Revolver” might be to suggest that Carlos Sastre’s narrow win in 2008 deserves consideration.

So what about 1969, the first of Eddy Merckx’s five victories, when the Cannibal won by over 17 minutes and picked up the points and King of the Mountains competitions? Or the one that saw the maiden win by another of the all-time greats: Bernard Hinault in 1978?

Delving much further back, there is Octave Lapize’s victory in 1910, as the Tour tackled its first major mountain range, the Pyrenees. Or there is 1947, when the Tour was reborn after World War II. An air of mystery prevailed. After a seven-year absence, there was no benchmark; there were no obvious favorites. That Tour had a thrilling and somehow fitting denouement when, on the final day, a little-known Frenchman, Jean Robic, attacked to claim his first yellow jersey at the point where it mattered most. It was a notable Tour for other reasons. It was the first organized by L’Équipe; it contained the longest successful solo breakaway, by Alberto Bourlon, who won stage 14 after being away for 253 kilometers, and it also presented the longest individual time trial — 139 kilometers.

Another barometer for greatest ever Tour could be how often a particular race is evoked in subsequent years. That happens a lot with 1986. It was that year that provided the reference point for 2009, when two of the favorites, Alberto Contador and Armstrong, lined up in the same Astana team. There was the familiar sense of an uneasy truce. “Just like 1986!” was the cry of many.

[related title=”More Tour de France articles” align=”left” tag=”Tour-de-France”]

Armstrong played the Hinault role as the grizzled old champion and patron, while Contador fulfilled the LeMond role as the fresh-faced young gun. And there were definitely shades of Hinault in Armstrong’s “ambush” on stage 3, in the crosswinds of the Camargue, when he made the split and stole some seconds on Contador. There were echoes here of the 16th stage of the 1986 Tour into Gap, when, buffeted by similarly strong winds, Hinault infiltrated the split along with two teammates, Niki Rüttimann and Guido Winterberg.

You will recall that Hinault instructed his teammates to ride on the front, distancing LeMond. And 23 years later, Armstrong instructed two teammates, Yaroslav Popovych and Haimar Zubeldia, to drive the break, distancing Contador.

Unexpectedly, the “greatest ever Tour” question received an airing again during the 2011 race. That owed too much, I think, to the closeness of the four riders at the top of general classification in the final week, and maybe to the identity of one of those riders: the man in yellow, with an outside chance of becoming the first home winner since Bernard Hinault in 1985. Plucky, gutsy, tenacious Thomas Voeckler, his tongue lolling, his face fixed in a look of fright, his body apparently permanently on the verge of collapse, defended the yellow jersey as though the pride of an entire nation depended on it. In the end, however, he couldn’t even retain a place on the podium, slipping to fourth as Cadel Evans became the first Australian winner.

A memorable Tour, then. But the greatest ever? I don’t think so, for the simple reason that it lacked an all-time great. It seems unlikely that Evans, the Schlecks, or Voeckler will ever be mentioned alongside Coppi, Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault, and the rest. Also missing was an edge to the various rivalries in 2011. There wasn’t the undercurrent of fear, suspicion, and intrigue that made 1986 — and other great Tours — so compelling.

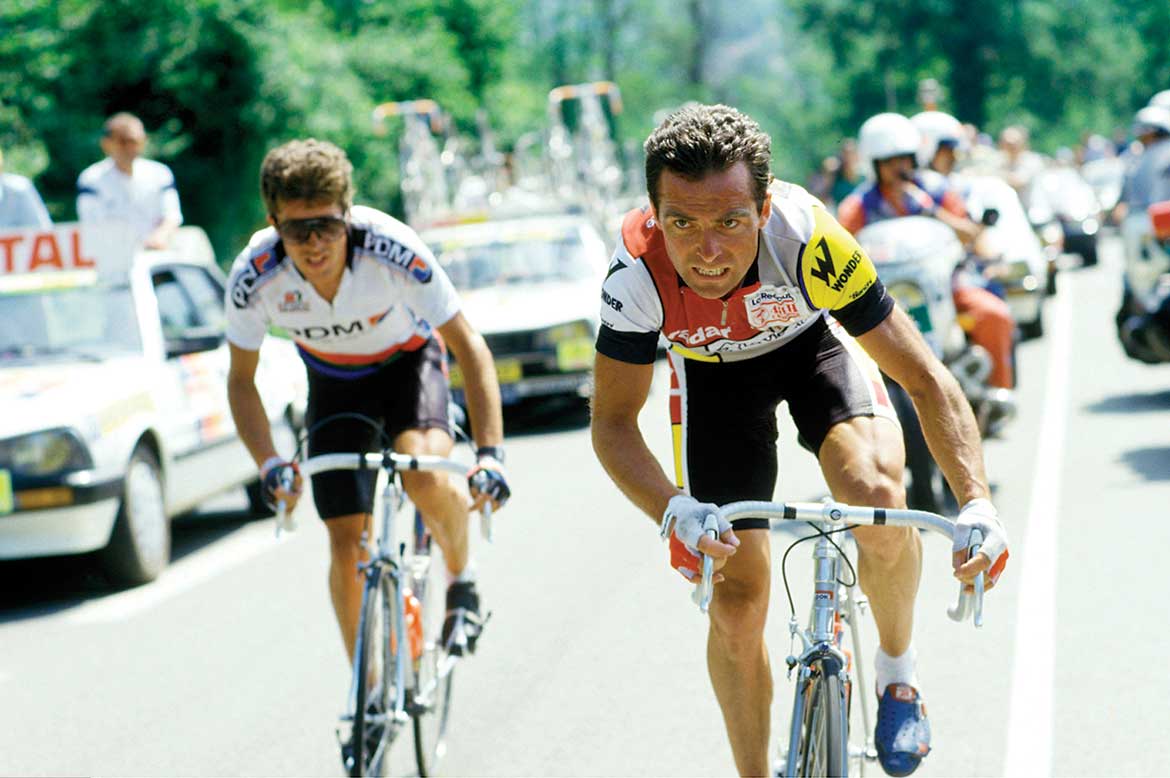

And so I return to 1986. It remains a Tour that meets all the criteria. It was a close battle. It was deeply symbolic, with the new world-versus-old world confrontation. It featured not one but two of the all-time greats. And there was an edge to their rivalry that was sharpened to a lethal point by the fact that they were teammates.

After my book was published, Urs Zimmermann, the man who finished third in 1986, sent me a long, idiosyncratic, quite wonderful e-mail. While he said the book gave him a new appreciation for the impact English-speaking riders have had on the sport since the 1980s, he said there is one episode in the book with which he was “not 100 percent satisfied.” It concerned the 17th stage, to the Col du Granon, during which Zimmermann and LeMond broke away behind the stage winner, Eduardo Chozas. It was the stage on which Hinault, in the yellow jersey, struggled with injury and LeMond took over the race lead. But there is, as Zimmermann put it, “a black hole.” It concerns the question of who attacked first: LeMond or Zimmermann? Maurice Le Guilloux assured me that LeMond “never attacked the yellow jersey.” Zimmermann suggests otherwise.

Zimmermann cast his mind back to that stage, and to what exactly happened on the climb before the Granon, the Col d’Izoard — or, more accurately, on the descent. It was here that he and LeMond went clear. It is a “black hole” because reports of what happened, and who initiated their escape, are vague and because the TV cameras missed the crucial action.

“It was Greg who did the initial attack,” Zimmermann wrote. “I was on his wheel, in the first sharp turns of the descent. Some other riders crashed at this point, and we were gone. In the second part of the descent I gave Greg some support, but overall, Greg did 90 percent of the work down to Briançon. And there was no team car.”

Zimmermann continued: “Finally, in this famous climb into Briançon, Paul Köchli moves up to Greg and says, ‘What the hell are you doing, Greg?’ This was the moment I knew; now it’s exclusively up to me to work.” The impression that day — formed by the footage of Zimmermann leading all the way up the Granon — was of Zimmermann leading the charge with LeMond sitting on, riding defensively. But Zimmermann witnessed something else.

“Up to that moment there was nothing that made me sure there was a war between Hinault and LeMond. Everything could have been a game of strategy, or the impact of Fignon’s failure. But, for me, Greg’s attack on the Izoard was evidence there was a war.”

Zimmermann drew a comparison to 1985, when LeMond escaped with Stephen Roche and was instructed not to cooperate. In 1986, Zimmermann found himself in the Roche role, only this time there was no team car to tell LeMond not to work. “You suggest that Greg never attacked the yellow jersey,” Zimmermann wrote. “But what about if he does? What a pleasure to have Greg as the bad boy for once!”

Zimmermann raised an interesting point. But given the wider context — what had happened in 1985, Hinault’s agreement to help LeMond, his repeated attacking, LeMond’s distrust of Hinault and others, the fraught atmosphere in the team — perhaps few would blame LeMond for breaking with protocol and, away from Köchli’s watchful eyes and with Hinault suffering with injury, seizing his chance when it came.

David Millar, an avid student of the history of the sport, also weighed in. “I have my theory on Hinault,” he told me. “He did keep his promise, is a man of his word, but the only way he could do that was by racing for the win in a totally reckless manner. His Pyrenean adventure, the kamikaze solo while in yellow, he did that because it was the only way he could satisfy everybody, the French people and his inner demons.

“If he pulled it off, which deep down he would have known he couldn’t, LeMond would have had no choice but to admit he didn’t deserve to win. But if he lost, he went down in flames satisfying those who wanted to see him win his sixth. His heroism and panache vindicated his pact with LeMond.”

If Millar is correct, you wonder if Hinault had it all thought out or whether such a rationale existed only in his subconscious. It is why Hinault continues to fascinate. Did he merely follow his instinct (“As long as I breathe, I attack”), or was he more calculating?

Up to that moment, there was nothing that made me sure there was a war between Hinault and LeMond. Everything could have been a game of strategy. But, for me, Greg’s attack on the Izoard was evidence there was a war.

A reaction from one reader, Gabriel Karaffa, from New York, prompted me to think about another aspect of the story. Karaffa noted that the 1986 Tour was “a stark example” of so many different people “pursuing their own agendas.” The problem, of course, was that so many of the dominant players — from the charismatic, wealthy team owner to the coaching genius to the two strongest riders — happened to be in the same team. In cycling, perhaps more than any other sport, this is a recipe for conflict. Because, as Karaffa noted, cycling “was not originally a team sport, but it evolved into one…The problem with this, of course, is that only one rider can win the general classification…Were it to completely convert to a team sport, all events would be decided by team classifications.”

Those of us who follow cycling closely accept that it is a team sport and rarely reflect on how unnatural this is. Perhaps it’s best described as an individual team sport.

But it is an aspect of the sport that cuts to the heart of the 1986 drama. Neither Hinault nor LeMond was drawn to cycling in order to become a member of a successful team. Teenagers do not embark on the road to a career as a professional cyclist harboring dreams of becoming a domestique. The team role is something that is forced on the majority of riders by their own limitations. For those without limitations — Hinault, LeMond — it is a near-impossible compromise.

With his kind permission, I end with Karaffa’s conclusion — which also returns to the question posed at the start of this story and represents a decisive vote in favor of that contentious subtitle:

“The combination of Tapie’s goals, Köchli’s lack of decisive leadership (though his hands may have been tied by Tapie’s goals and Hinault’s personality), Hinault’s inability to plot a moral course, and LeMond’s desire to win (coupled with his unparalleled strength) created what you have described as ‘The Greatest Ever Tour de France.’ Every other race has paled in comparison.”

Excerpted from “Slaying the Badger,” by Richard Moore. Copyright © 2012. All rights reserved.