Tour time: 16 years on the sport’s biggest race

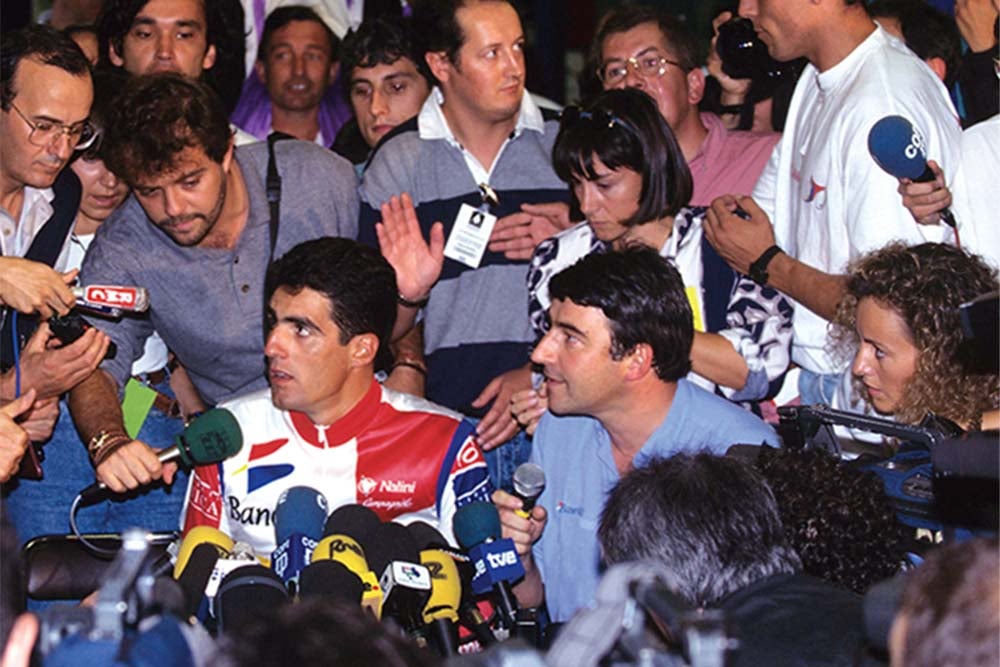

Miguel Indurain meets the press in a very different era indeed. Photo: Graham Watson | <a href="http://www.grahamwatson.com">www.grahamwatson.com</a> (file)

Tour de France press officer Philippe Sudres slammed his palm on the table inside the press room for the Grand Départ of the 1996 Tour de France: “Atención! Conférence de presse avec Miguel Indurain commence!”

On a damp summer evening in Holland for the start of the 83rd Tour, Big Mig was at the height of his powers. The five-time Tour winner’s tall, lean, bronzed frame stood in sharp contrast to the slouched shoulders and bulging paunches of the press rabble.

The pushing and shoving was tremendous. Journalists, photographers, and TV crews leaned in to hear Indurain, who was on the cusp of becoming the first rider in Tour history to win six yellow jerseys. In an era before Twitter and Facebook, you were either there or you missed it. Indurain didn’t say much. And when he spoke, it was a rapid-fire whisper, as if he were spitting out marbles one at a time.

Some three weeks later, it was Bjarne Riis, not Indurain, who would claim the yellow jersey. The peloton’s “Mr. Sixty Percent,” so named for his hematocrit level, toyed with Indurain and the rest of the peloton, defying gravity and logic to win the Tour. The Champs-Élysées was converted into a red sea of flag-waving Vikings as half of Denmark invaded Paris. It was Riis’s first, and last, Tour win.

Now, everyone knows how that story ended. In fact, the ending’s been the same for almost every Tour during the EPO era, from Riis to Lance Armstrong, and more, before and since. The tricks, the deceit, the cheating, the lies; it’s all been neatly catalogued for everyone to read. Winners erased, winners with asterisks. From the time EPO gripped the peloton in the early 1990s until just a few years ago, if we dare to believe that true change from within is possible, the history of the Tour over the past 20 years reads like a torrid spy novel.

And I had a front-row seat for most of it — the good, the bad, and the very ugly. From the Festina Affair to Operación Puerto to the U.S Anti- Doping Agency’s inquiry into the Armstrong doping conspiracy, there has rarely been a dull moment.

There’s no more denying it. Doping and cycling were joined at the hip, like a crank that ran on vials, into the veins, via the heart and lungs, out to churning pedals. What now seems so obvious was hidden behind a wall of silence, fear, retribution, incompetence, and greed.

Perhaps it’s appropriate that the 100th Tour began under the banner of “new cycling” that somehow felt different from anything we’d seen before. It’s a flag that’s been flown several times over the past half-century, ever since doping controls began in the 1950s and 1960s. But the past few Tours have looked radically different from anything we’ve seen over the previous two decades.

Figuring it out

That Indurain press conference was my first. And hopefully this year’s in Corsica will not be my last. In 1996, I was among a new wave of journalists hitting the Tour thanks to the magic of the Internet. Scribbling stories for Outside magazine’s nascent website and The Associated Press, I was thrown to the wolves, not knowing much at all about how the Tour worked. My editor in Paris said with a shrug, “You will figure it out.” For a reporter, the Tour is a huge, ugly beast from within, and without a doubt the most challenging event to handle, logistically, physically, and — as us front-line hacks all soon discovered — ethically.

It’s hard to remember how I survived that first Tour at all, in the days before GPS and cell phones. It could be maddening. One seasoned American journalist, who had covered Super Bowls, Final Fours, and World Series, showed up one day in the pressroom with a black eye. Asked if he had been roughed up in a low-rent bar, he finally recounted what happened: “I could see my hotel, but couldn’t get to it. After an hour of driving around, I finally lost it, and punched myself in the face.”

In my first Tour, I was hopelessly lost in the approaches to Paris. Desperate to arrive in time for the final stage on the Champs-Élysées, an official Tour de France car drove past. Assuming he was headed to the finish line, I got in behind him. After about 20 minutes of swerving in and out, he stopped and got out of his car. “You are following me, yes?” Er, um … oui, I replied. “I am not going to the Tour. I am going to my mother’s house for lunch!” Needless to say, I didn’t have time to accept his invitation.

A few nights were unexpectedly spent under the stars in hayfields or along a riverbank. One time I pulled off near a farmhouse in southern France and rolled out my sleeping bag. The owner came up, and spying my press sticker on the car, said I could sleep in his house for free. “I always liked that LeMond fella. Come on, sleep with us, vive Le Tour!”

But I wasn’t complaining. Just holding a press credential at the Tour was like a dream come true. Before the Internet, only a few Americans managed to cover the Tour — a crew from VeloNews, Sam Abt from The New York Times, and maybe a few others, but it was a small band of brothers in those days.

The media landscape has changed as dramatically as the peloton. Long before 4G and the immediacy of updates on your cell phone, just getting online was a major achievement. I remember that glorious screech of the modem connection, like someone scraping fingernails down a chalkboard. It was better than Beethoven. Now, fans have the luxury of watching the Tour live on TV, and can get direct reactions from the riders via social media. The news is no longer who won, but how they did it. The story behind the headlines is what everyone is chasing today.

That first experience of the 1996 Tour got me hooked. Anyone who has watched the Tour knows the feeling; there is simply no other sport like it. The stadium is L’Alpe d’Huez one day, Mont Ventoux the next. Rain, wind, heat, even snow — there is little that can stop the peloton once it starts spinning toward the finish line.

Back in 1996, my editor suggested I go a day early to Spain to report on how the Spaniards were taking Indurain’s imminent loss. Ready for some of Spain’s famous nightlife after nearly a month of missing dinners in France, we trotted into Pamplona’s historic city center ready for fun. We were dismayed to find the streets empty at 9:30 p.m. We found an “asador” with only a few patrons, and asked with relief if it wasn’t too late to dine. The waiter shrugged his shoulders and pointed us to a corner table. Of course, we were too early. By the time a band of Spanish journalists rolled in to eat at nearly midnight, they laughed, “Ah, look, the Americans are already having dessert!” When we hit the street, it was so crowded with revelers we could have bodysurfed from bar to bar. The next day, the small Spanish cafés were all full of dismayed fans as their beloved “Miguelón” succumbed to Riis.

And being part of the Tour entourage is unlike any other sporting event. While the Olympics are bigger in scale and volume, and the Super Bowl is louder in hype and commercialization, the Tour remains true to its French roots, keeping it unique to the nation and culture. It is more than a bike race; it is part of the French cultural landscape, an essential rite of summer, passed down from generation to generation.

The Tour’s roving caravan becomes professional sport’s largest moving city, with more than 5,000 riders, sport directors, soigneurs, mechanics, podium girls, race officials, jury members, drivers, journalists, and a few hangers-on — and now, we hope, a few less dope runners — all sweeping across France like an invading army.

The Tour sets up camp like carnival hawkers, explodes in a fury as the stage winner crosses the finish line, then quickly packs up and leaves in the middle of the night, hurtling blindly toward another village or city. The French are loath to change their dining hours, even when the Tour rolls into town. Restaurants will close at their appointed time regardless of how many haggard journalists are begging for a meal. Waiters seem to take a sadistic thrill from wagging their fingers in their faces, pointing to watches at five minutes past 10 p.m., and saying, “Ah, too bad for you! Zee kitchen is closed!”

Like the riders say, the Tour remains the sport’s most important race, not so much for the prestige and history that come with cycling’s first grand tour, but rather because it’s the one race of the year where everyone brings his “A” game. No cyclist lining up in Corsica will be using the Tour to prepare for the Tour of Poland in August. From the water carriers to the GC captains, just about everyone who has made his team’s “Tour Nine” has been dialing in his mind and body since November to be there.

Because the riders’ fitness is so high, the Tour can sometimes seem neutralized, a function of the differences between the top GC contenders, which can be fractions of a fraction. Riders are shaved to the bone, walking a tight rope of top form, trying not to fall off the other side. Other races, such as the Giro d’Italia or Vuelta a España, can be wildly unpredictable because everyone is all over the map on form. Only at the Tour is the entire peloton at its absolute peak for three glorious weeks.

The most wanted

The pro peloton remains an unruly bunch of characters. A glance down the stage winner’s list of that 1996 Tour reads like an FBI “most wanted” list of EPO users. And there is no sport that produces such disparity of personalities as cycling. The demands of the sport draw the narcissists, the natural-born freaks, the flamboyant, the loners, and the unscrupulous.

It often strikes me how global and democratic the sport has become. The Greg LeMond generation broke the Euro stranglehold on the peloton in the 1980s. Even from my first Tour in 1996, into the second decade of the new millennium, the peloton is a very diverse workplace. Today, there is no sport as international as cycling. This year a rider born in Kenya is the spot-on favorite to win, with Australians, North Americans, some Europeans, and perhaps some Colombians within reach of the podium. Nearly every continent is represented in this year’s Tour — though, as far as I know, penguins aren’t racing bikes yet.

The last Frenchman to win the Tour was Bernard Hinault, the man known as The Badger, in 1985. Today Hinault works for the Tour organization, and vigilantly guards the podium from would-be protesters and overzealous fans. In many ways, Hinault was the last true heroic figure of the peloton. Today’s pros are too accessible, too politically correct, and too congenial to evoke pure hero worship. Can you imagine Chris Froome punching strikers who might dare to block the road?

A time to believe

There’s been a lot of hand-wringing in the fallout of the USADA case against Lance Armstrong and U.S. Postal’s doping regime, and rightly so. Cycling was a corrupt, dope-riddled sport top to bottom, built on cheating the system and winning at any cost. It was like the Wild West, and there was no sheriff in town. And once the tests started coming, first with the EPO test in 2001, and later with increased out-of-competition controls, it became a high-stakes game of evading detection.

Many are quick to cast anyone who ever doped as a villain, a scoundrel, a rogue unworthy of rehabilitation or second chances. Over the past two decades of reporting on cycling, I have interviewed nearly every major star that has come down the road, many of whom have tested positive or had some sort of doping innuendo cast upon them. And every time, they lied to my face, and everyone else’s. They became convincing, professional liars; it was a skill that became an essential part of being a pro racer. Asking a cyclist if he was doping was akin to asking someone if he was having an affair. They would deny, deny, deny, until the private investigator produced the proverbial photographs to prove it.

And there was no one more masterful than Lance. Armstrong kept everyone dancing, because he knew access was key. Ask hard questions, and you never got one-on-one interviews (hence David Walsh’s famous press conference showdowns with Armstrong). Suck up to him, and you would get insider stuff, private phone calls, and sometimes flights on his private jet, or a personal visit at his ranch.

Armstrong played all of the media off each other: ESPN and Sports Illustrated; VeloNews and Cyclingnews.com; L’Equipe and La Gazzetta dello Sport. All of us were dancing to Armstrong’s tune one way or another. I tried to play it in the middle; not too negative, but not a total suck-up, either. Of course, looking back now at what we all know, we should have played it tougher on the EPO generation; but when you’re waiting at the finish line at the end of a 200km stage, and you need quotes for a story, that’s not the time or place to ask about someone’s blood-doping program. That’s not making excuses, just the day-in, day-out reality of chasing bike races across Europe. At one point or another, on and off the record, we all asked these guys if they were doping. They all lied to our faces.

Armstrong would typically give me one sit-down a season. There’s been a lot of people piling on Big Tex over the past year, and rightly so, but any hack who interviewed him will agree he was the most engaging, most intriguing, most intelligent interview you would get. Even better were those times when Armstrong would call journalists in private, one-on-ones, to shake them down, to intimidate them, to feel them out. He called one English journalist a “snake with arms,” another was “worse than Saddam Hussein.” Once he called me, berating the “Boulder crowd,” saying if VeloNews had played it differently with him, we’d be “one phone call away.” Instead he went on a 20-minute monologue about how he hated VeloNews.

At the height of the Armstrong story, there were about a dozen journalists on the ground during the Tour chasing him. A friend from L’Equipe and I would always joke when the stage was nearly ending: “Lance time!” As his story got bigger, so did Armstrong’s ego, and it wasn’t as fun. Access was harder and more limited, and more often than not, it was nearly impossible to get anything “exclusive” with Armstrong. There was Armstrong’s infamous “blacklist,” which I was either on or off, depending on what I was writing about. For me, Armstrong was a story; I never took it personally. If he talked to me, great; if not, well, there were 200 other riders in the race.

Armstrong’s fall from superhero status to the lowest of the low is just the latest, most sordid chapter in what’s been a torturous, yet ultimately fascinating road for cycling. The Armstrong scandal, as negative and gut wrenching as it’s been, is the best thing that could have happened in cycling. It provides a chance to turn the page, draw a line in the sand, and speak openly about the past — and more important, the future.

Yet few of the EPO generation were inherently bad people. Tyler Hamilton would always ask how someone’s wife was doing, or wish them a happy birthday. George Hincapie is one of the nicest guys I have ever met in my life. Marco Pantani was perhaps the most peculiar, and ultimately the most tragic. I only once interviewed him one-on-one, and that was through a camper van window at the Vuelta a Murcia. Pantani kept referring to himself in the third person. “How do you expect to challenge for the Tour?” I asked. “Well, Pantani will attack. Pantani always attacks. …”

Most of that generation was simply forced to make choices in an era when there was no choice, at least if they wanted to continue to race bikes professionally. A few principled people walked away; others tried to race clean. They are the true heroes. Most of the survivors of the EPO era made very different choices once they had one. I believe that riders like Christian Vande Velde and Tom Danielson have been on the straight and narrow for a long time, once they were in an environment that allowed them to make the choice. And there are dozens, if not hundreds, of other top pros just like them. Too, riders like Bobby Julich, who had the courage to publicly admit he doped when he knew it would get him fired at Team Sky, are important voices for the peloton, to help the new generation not repeat the same mistakes they made.

But just as terrible as the past 20 years have been, there’s tremendous reason to be optimistic at the start of this year’s Tour.

A dramatically different cycling culture has taken root. While doping and cheating can never entirely be erased, the norm has gone from doping to being dramatically cleaner in a relatively short time span. Hamilton talked about how, at the 2004 Tour de France, there might have been “one or two” clean riders at the start. Less than a decade later, today’s peloton will line up in Corsica with that proportion almost turned on its head. While it’s naive to suggest that only one or two dopers remain in the peloton, the vast majority of riders will be clean. The biological passport, coupled with stronger team ethics (and intense sponsor pressure), and an endless string of crippling scandals, has all added up to a cleaner sport. If cycling displayed an inability to clean up its act, it simply would not have a future.

There’s a different tone and feel to the interviews with today’s pros about doping and the doping culture. Both on and off the record, riders continue to press how much the sport has changed. Younger pros insist they’ve never seen a needle, nor been offered one. For the most part, I tend to believe them.

Today’s younger pros, and even some reformed dopers, all deserve a chance. So far, over the past two, maybe three seasons, they seem to be holding up their end of the bargain. Work that began with Jonathan Vaughters, Bob Stapleton, and many others in 2006 to 2008 is paying off with huge dividends.

When given the choice to dope or abstain, most are choosing the latter. In fact, they are embracing it. Credible riders are winning cycling’s biggest and most important races.

Back in 1996, I was excited because I couldn’t believe the luck I had to gain a front-row seat to one of sport’s most amazing spectacles. This year, I feel even more excitement about where cycling is going. It’s a time to believe in cycling again. I am enthusiastic to watch how riders like Andrew Talansky, Tejay van Garderen, and Richie Porte will flourish in the coming years. They all insist they’re clean, and this time around I believe them. They not only act like they have nothing to hide, they race like it. When someone rides away from the others in this year’s Tour, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve doped better than everyone else. It could also mean that they’re simply better.

That’s what cycling should be, and for the first time in a long time, that’s the kind of racing we will all be watching in this year’s Tour.

The fine qualities that have always made the Tour so great are still there. They’ve always been there: the eternal charm of France, its back roads, its people, and its cycling pedigree, which lured everyone to the Tour from the start. Without the shadow of doping to get in the way, it should shine even brighter.

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the August 2013 issue of Velo magazine.