Places of cycling: A kind of blue

In the summer of 1947 three young friends went to the beach in Nice, France. One of the trio was Yves Klein, a nineteen year-old student who’d been born and raised in the city. As they lay back in the sunshine, the three men discussed how they might divide the world between them. Arman, an artist who later became a naturalized American, took the earth. Claude Pascal, a composer, claimed words. Klein chose the sky. Later he said, ‘As I lay stretched upon the beach of Nice, I began to feel hatred for birds which flew back and forth across my blue sky, cloudless sky, because they tried to bore holes in my greatest and most beautiful work.’

Whilst studying in Nice, however, Klein became equally obsessed with a more worldly pursuit: judo. On graduation he travelled to Japan to study at the Kodokan Judo Institute in Tokyo, becoming the first European to become a 4th degree black belt master. After travelling around Europe, in 1954 he settled in Paris, where he wrote a book on judo before turning his attention to art.

His first shows in Paris were composed of a series of monochrome canvases, each painted in bright colors to represent a place he had travelled to in the preceding years. Klein was disappointed to discover that many visitors interpreted the monochromes as a mosaic, a kind of colorful decoration. His response was to focus on one colour. Blue. And he wanted to make that color so intense it would have a profound effect on the viewer. Working with a Parisian paint supplier, he created an ultramarine pigment suspended in a resin. The new formulation meant that the intensity of the pigment was maintained indefinitely. In conventional paint pigments tended to dull over time. Klein trademarked his ‘new’ color, naming it International Klein Blue (IKB). Thereafter he worked almost exclusively in IKB, occasionally adding his other favoured colors, gold and rose. His vivid monochrome canvases were an immediate hit with the public, and he went on to use IKB on plaster cast statues and paintings of the human form. He even strapped an IKB canvas to the roof of his car and drove from Paris to Nice; exposed to the elements, the canvas made a visual record of the journey’s weather.

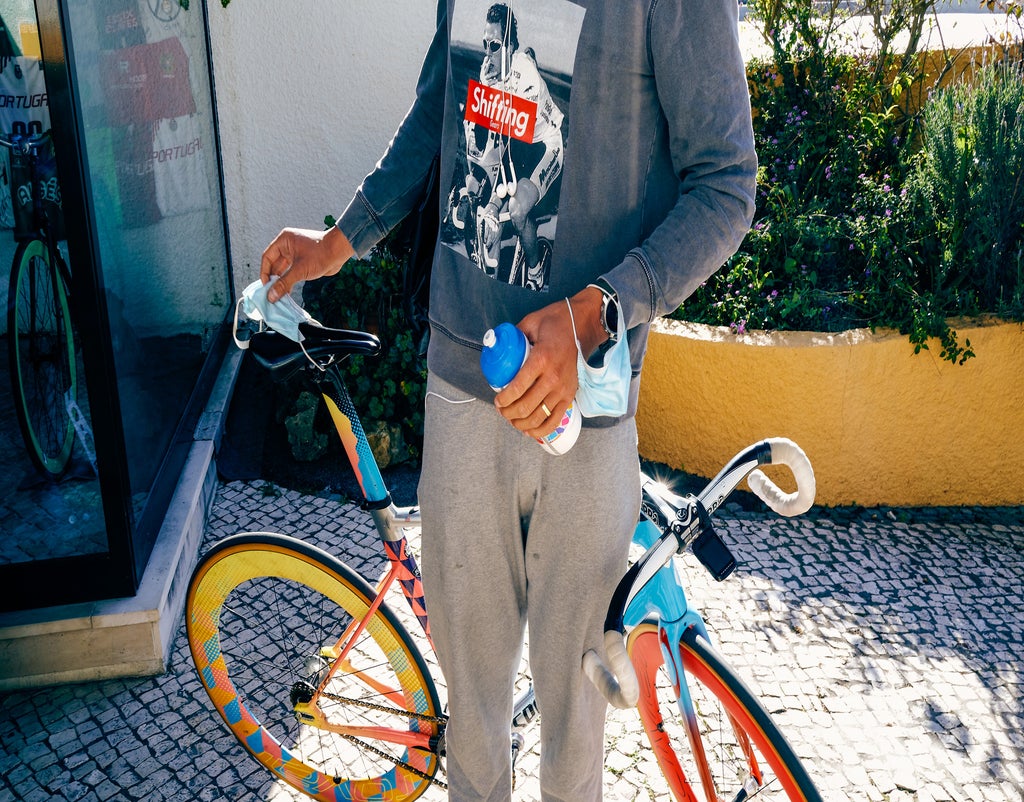

There was, of course, much more to Klein’s art than IKB. He was a pioneer of performance art and pushed the boundaries of photography. In 1960 he and some friends produced the famous photograph ‘Leap into the Void, Fontenay-Roses’, part of the permanent collection at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The image shows Klein, dressed in a suit and white shirt, in mid-air, having leapt from the roof of a building on a suburban street in Paris. He is headed for a very hard landing on a cobbled street. On the other side of the street a man pedals past on a bicycle, oblivious. The photograph was a trick; a composite of images that hid whatever soft-landing Klein was really heading for (he never gave away the secret but there was speculation he piled up judo mats on the street).

Klein died at the age of 34. Whether expressing it through color, or leaping into it, Klein was fascinated by the idea of the void, a state free of earthly influences and representation, where the artist and the viewer paid attention to a deeper reality. Klein chose to use visual art to express this but stripped that art of its usual forms. There was only the absence of form, visual silence. His work may have coincided with the New York school of Abstract Expressionism, but his version of abstraction was altogether more playful and inventive.

The greatest artists are undoubtedly hard workers. Yet it also pays to lie on beaches in the South of France and gaze at the sky. That’s something we should all remember.