30 chain lubes lab tested for efficiency

Friction Facts lube efficiency test machine. (Photo: Brad Kaminski)

This test ran in the March 2013 issue of VeloNews.

Lube is unquestionably the cheapest way to make your bike measurably quicker.

The results of our third-party testing, commissioned by us and performed by independent lab Friction Facts, are extraordinary. The difference between the most- and least-efficient chain lubes is not just a marginal gain. There is no cheaper way to save watts.

Attaining maximum drivetrain efficiency has long been an endeavor of the detail-oriented mechanic, stopping at nothing to minimize drag on the day of a big event. Bearing seals are removed; grease is replaced with light oil; ceramics are used in place of steel. Frequent cleaning and replacement remove durability and longevity as concerns, opening up a world of potential efficiency gains.

That’s why our test centers on efficiency. We didn’t ask Friction Facts to pick the best lube across every weather condition or every rider — that, frankly, is impossible. Some of the best lubes in this test likely would disappear completely after a few hours in the rain; others would never make it through even a dry-weather training week. But durability was not our concern.

We asked Friction Facts only to determine what lube makes a drivetrain most efficient, to identify the concoction that most effectively slickens the hundreds of metallic contact and rotation points on a chain. We had one primary question: Among 30 highly popular lubes, which will make you fastest on race day?

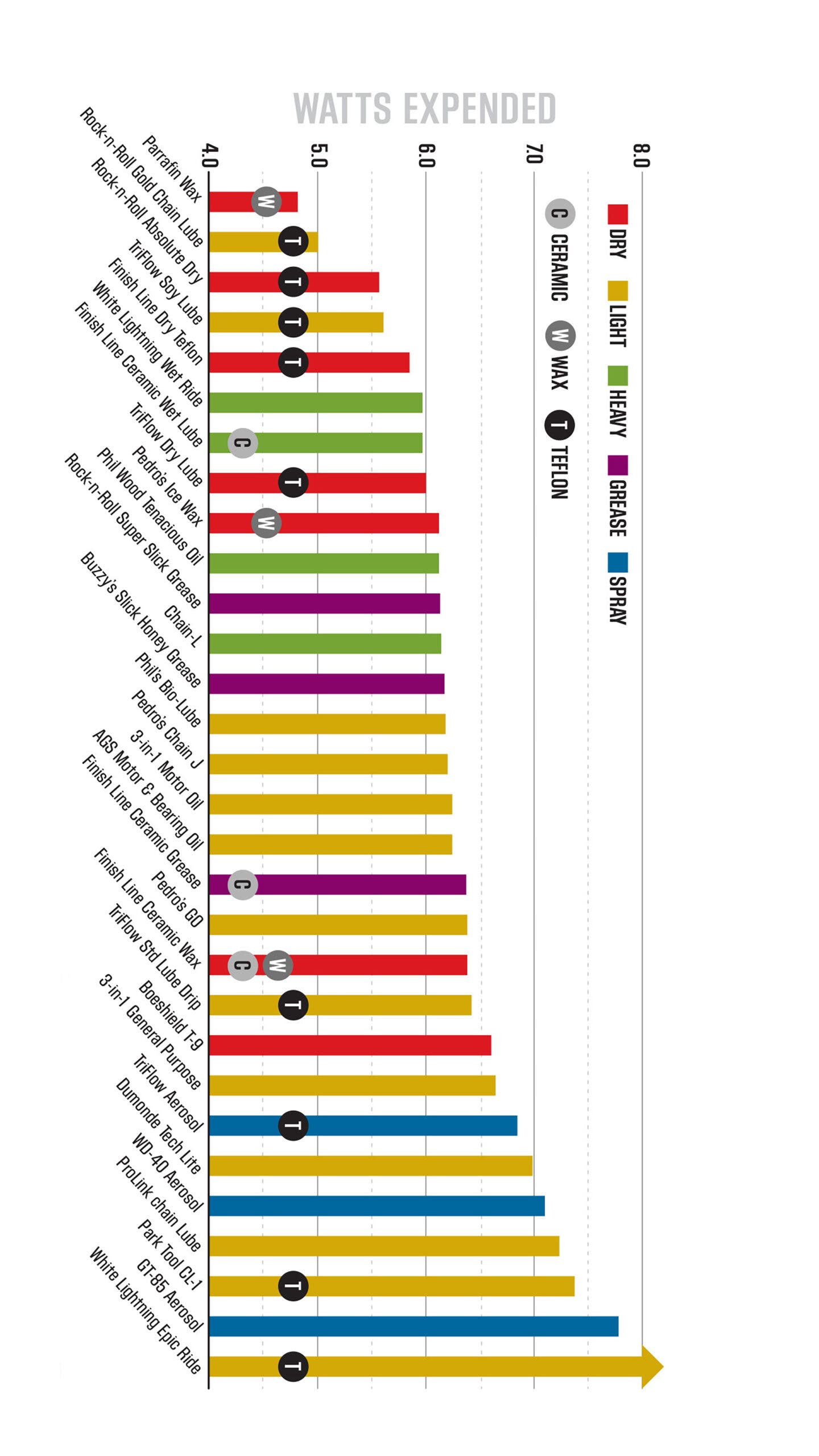

Efficiency results

The fastest bike lube isn’t designed for your bike at all. In every measure, the most efficient chain lubricant is simple paraffin wax, sold in solid blocks at any hardware store. In the efficiency test it was faster than the best bike lube by 0.24 watts and the

worst by 3.05 watts under ideal conditions. Following an hour covered in dirt, sand, and water, the paraffin was nearly 6 watts faster than the worst performing lube.

That’s similar to changing from a low-quality training tire to a super-thin race tire, or from a cheap aero wheelset to the best available. Best of all, paraffin wax costs less than $10 for a few blocks, which will last months, if not years. Rock-n-Roll’s Gold chain lube is far and away the most efficient bike-specific drip lube we tested.

Minimal solvent and a healthy heap of PTFE (Teflon) are both visible in the bottle, helping to make Gold 0.51 watts faster than the next fastest drip lube.

Unsurprisingly, the lubes loaded with PTFE, the same material that keeps your eggs from sticking to the pan, tended to perform the best. Rock-n-Roll’s Gold led the charge, followed by the company’s Absolute Dry concoction. TriFlow’s light Soy Lube, which uses Teflon, was in the mix as well. All of the top four drip lubes are based around the stuff.

The regular oils stacked up in the middle, and oil weight didn’t seem to play a large role. Heavy oils like Phil Wood’s Tenacious Oil were quicker than some lighter ones, like Pedro’s Chain J. But more on viscosity later.

The lubes containing a significant amount of “carrier,” designed to evaporate quickly after application, were by far the worst of the bunch. The aerosols, which are mostly carrier, were all clumped in the last quarter, and the slowest by a large margin was White Lightning’s Epic Ride Light Lube, which is also mostly carrier.

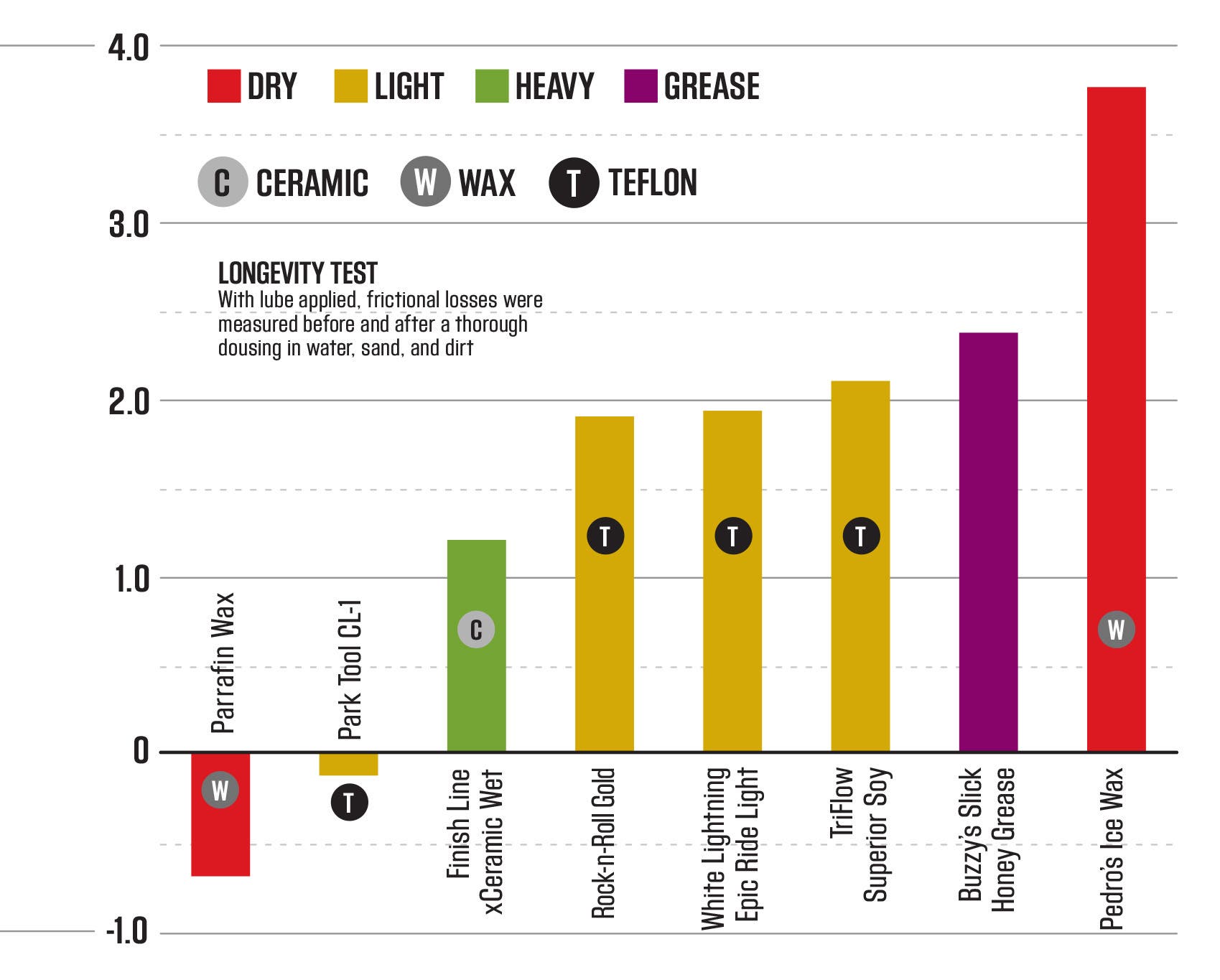

Longevity results

We tested eight of the lubes for longevity, simulating a single dirty, wet ride and testing efficiency before and after. Each of the eight was chosen as a representative of a certain lube type. For the most part, four of the eight, representing greases, wax-based drip lubes, regular oils, and biodegradeable oils, were all very similar, losing about 2 watts over the hour-long test.

Once again, the old technology of paraffin wax vanquished all comers. In the longevity test, it was completely unperturbed by water, sand, and dirt; in fact, it was over 0.5 watts faster after being run for an hour in the grime. We believe that the wax needs to bed in a bit for maximum efficiency. And, since nothing really sticks to it, the goop was simply shed before it could slow anything down. The only other lube to increase efficiency after the dousing and dirtying was Park Tool’s CL-1.

Pedro’s Ice Wax performed the worst of our eight representative lubes, requiring more than 3.5 additional watts to turn around. By the end of the hour-long test, the chain with Ice Wax on it was completely dry. The super fast Rock-n-Roll Gold jumped nearly two watts after the grime run, as did the Buzzy’s grease, TriFlow Soy, and Finish Line Ceramic. The Gold lube also began to dry out, and was running audibly louder.

This, of course, points to the obvious: The most efficient lubes in perfect conditions are likely not the fastest when the going gets rough, with the exception of paraffin. Park Tool’s CL-1 is a good standing for a number of mid-weight, oil-and-Teflon based lubricants near the bottom of the efficiency ranking, and its excellent performance in the longevity test bodes well for that lube type in bad conditions. If your race day is also a rainy day, something with more carrier and a light oil might be the way to go.

Viscosity

The viscosity results, which were designed to measure how quickly a lube will work its way into a chain, were largely inharmonious with the efficiency testing. It seems clear that the contents of a lube are far more important to its dry-weather performance than the viscosity, with both very thin (like the Rock-n-Roll Gold) and very thick (like White Lightning’s Wet Ride)

lubes doing quite well in the efficiency testing.

In fact, even the longevity test didn’t correlate very well with viscosity. TriFlow’s Superior Soy lube was highly viscous and was decidedly average in the longevity test, while the thinner Park CL-1 did very well. The only firm conclusion we can draw is that some light lubes, like the Pedro’s Ice Wax, will wear off quickly, and efficiency then plummets — not that this should surprise anyone. The more viscous lubes, in general, seem to hold onto the chain better, making them more durable. This is why rainy

days will see many pro mechanics use a heavy oil first then cover the chain with grease, in an attempt to lock in the lubricant.

The takeaway

The only real argument against paraffin wax is its more intensive application process. It’s obviously the fastest in ideal conditions, and even in nasty conditions it is still an exceptional single-day lube. On our test bikes, it has sloshed through hours of snow-covered roads without a squeak or squeal, remaining clean enough to touch the whole time; it will live through just about anything you can throw at it in a single day.

In real-world testing, we’ve been getting upwards of 650 miles out of an application (shortened by about half if riding in wet weather) before the chain begins to dry out. When the wax hits the end of its life, it does so quickly and dramatically: your drivetrain will go from quiet to raucous in the space of a few minutes. So, it is best to re-apply relatively frequently. Whether it’s simply too much effort to bust out the crock-pot every half dozen rides or so is, of course, up to you.

Among the normal drip lubes, a few themes stand out, many of which are visible right in the bottles themselves. The oils all performed alike, so pick one based on the desired viscosity. Thicker will stay on the chain longer, in most conditions, but will also be dirtier. The fastest heavy oil, and therefore perhaps the best choice for consistently bad conditions, is White Lightning’s Wet Ride.

The drip waxes don’t last long, and are only effective if the quantity of wax is very high — as with Pedro’s Ice Wax. Too much carrier, and the lube will perform terribly. If the clean drivetrain that wax lubes offer is that appealing, one is better off buying some paraffin.

The lubes that contain large amounts of slick additive, like PTFE or wax, relative to their concentration of carrier, are almost always faster. The fantastic Rock-n-Roll Gold has huge amounts of PTFE, a bit of oil, and some carrier, all distinctly visible through the side of its clear bottle. Rock-n-Roll Absolute Dry drops the oil and ups the carrier, but also ups the PTFE even further, keeping it near the top of the list. The lubes with lower PTFE or wax-to-carrier ratios always performed worse — in fact, the bottom quarter of the efficiency test is chock full of them.

It’s clear, then, that going for a lube with as much PTFE as possible is the best bet for pure efficiency. For consistently wet weather, go with heavy oil. And for the meticulous mechanic, happy to pull a chain off and re-wax it every few weeks, cheap hardware store paraffin is unbeatable.

How it was done

Friction Facts owner Jason Smith performed three tests, examining for pure efficiency in ideal conditions, longevity, and lube viscosity. All thirty lubes were put through the initial efficiency test and the viscosity test, while eight lubes representing various categories went through the longevity test.

Efficiency test

Each lube was tested on three top-of-the-line chains, one each from Campagnolo, SRAM, and Shimano, and the final results are an average of all three. The chains were cleaned with an ultrasonic cleaner in odorless mineral spirits prior to testing, and then all three chains were immersed in a 100˚F bath of each respective lube and run in the ultrasonic machine for five minutes. The greases were worked in manually.

The chains were then hung to dry for thirty minutes, wiped clean, then mounted on the test equipment, always facing the same direction. Chain tension simulating 250 watts of rider output was applied, and each chain was run for five minutes, with data captured at the end of each five-minute run. The system is accurate within +/- 0.02 watts, and system losses from the four ceramic bearings in the equipment were subtracted from the final results.

Longevity test

The same three chains were used for this portion of the test, and each chain was thoroughly cleaned between each round of testing using the ultrasonic machine.

Each chain was tested as in the initial efficiency test to acquire a baseline for each lube. The chains were then moved to another tester, which applied the 250-watt load but did not measure efficiency, so that water and grime could be applied. With the chain spinning under load, gravel and dirt were sifted onto each chain for 30 seconds, then the chains were sprayed with 30 full pumps of an industrial spray bottle, then another 30 seconds of dirt was applied. The equipment was allowed to run for 60 minutes while covered in dirt and water.

Each chain was then placed back on the efficiency tester for another reading and results were gathered relative to the baseline.

Viscosity test

This simple test was intended to determine how well each lube could work its way into a chain. All 30 lubes were dripped on a steel plate placed at a 30-degree angle. Each lube was dripped 10 times; the time was started when the first drop hit the steel, and the lube was allowed to flow 10 inches. When the lube hit the 10-inch mark, the timer was stopped.