Technical FAQ with Lennard Zinn: LZ suggests some New Year's resolutions for the bike industry

Editor’s Note: Tech writer Lennard Zinn made a few resolutions this New Year’s Day — for the bike industry. Below he shares three suggestions, starting with the way bikes are measured:

Resolution for Frame Manufacturers: Use Stack and Reach to Denote Frame Size (and measure it to the top of the headset upper bearing cover).

Frame sizing was simple when steel lugged frames with level top tubes were king. There was variation in where the frame size (i.e., seat tube length) was measured to, but once that was sorted out, you could almost compare apples to apples by simply listing the seat tube length and the top tube length, both of which could be measured directly along the tubes.

Now, however, due to sloping top tubes, extra head tube and seat tube extensions above the top tube, integrated headsets (heck, even threadless headsets alone threw off frame sizing), and wide variations in seat angles on bikes designed for aero bars, frame size is very hard to define. A rider who fit well on a 56cm lugged frame with a 56.5cm top tube now might have no idea of how to determine whether a given frame would fit the same. The bike would need to be built up and standing on its wheels in order to measure the top tube length, which is an “effective” top tube length, measured horizontally from the center of the top of the head tube to the center of the seatpost. And the up-sloping top tube ensures that all of the possible measurements from the bottom bracket center to the top of top tube, to the top of seat tube, or to the center of top tube would be less than 56cm.

Enter “stack and reach,” the system pioneered by Dan Empfield, founder of slowtwitch.com and Quintana Roo, to effectively characterize frames so that they can be compared with the purpose of determining if they would fit a given rider. To use this system, you only need two points on the frame: (1) the center of the bottom bracket and (2) the head tube centerline intersect with the top of the head tube (and I think this should be changed to the head tube centerline intersect with the top of the upper headset bearing cover to correct for internal vs. external headsets).

The vertical distance between those two points is the frame’s stack. The horizontal distance is its reach. The frame size is then listed in the format “580/390,” which would mean a frame with 580mm of stack and 390mm of reach.

Why would you care about stack and reach? Well, consider four different 56cm road frames, all of which have a 57cm top tube. Frame A has a level top tube, frame B has a sloping top tube, frame C has “comfort geometry” with extra head tube extension above the sloping top tube, and frame D is a time trial bike with a 78-degree seat angle whose level top tube intersects the seat tube a few inches below the top of the seat tube in order to lower the front end to account for the height of the elbow pads. Assume that all four frames have the same bottom bracket height and are built for 700C wheels and the same headset type.

It should be obvious that the head tube length of frame A will be shorter than that of frame B, which will in turn be shorter than that of frame C, and the head tube of frame D will be shorter than any of them. This means that the handlebar, if set up with the same headset, spacers, and stem, will be at different heights for all of them. So, the saddle-to-handlebar drop will be different for all of them. This will create the same kind of fit issue as if the seat tubes were all different lengths.

Now consider the seat tube angles. We said that frame D has a 78-degree seat angle, and let’s give frames A, B, and C seat angles of 73 degrees, 73.5 degrees, and 74 degrees, respectively. Obviously, to position the saddle the same relative to the bottom bracket on all four, the saddle will be pushed further back on the seatpost on frame D than on frame C, which will have its saddle in turn pushed further back on the seatpost on than on frame B, which will in turn have its saddle pushed further back on the seatpost on than on frame A. This means that the distance from the saddle to the bars is greater on frame D than on frame C, which in turn is greater than on frame B, which in turn is greater than on frame A. If you think of the effective top tube length as being something related to the distance from the handlebar to the saddle, it is obvious that the effective top tube lengths of these frames are all different, even though their measured top tube lengths are the same.

Now that you see its importance, how do you actually measure the stack and reach of a given frame? First off, you have to do it when it is built up with its fork, wheels and components.

When the bike is standing on the floor, measure from the floor to the center of the bottom bracket and from the floor to the top of the head tube. The difference between these two values is the frame’s stack.

Have a friend push the bike head-on against a wall, perpendicular to it, with the tire touching the wall. Measure horizontally from said wall to the top center of the head tube. Measure horizontally from the wall to the center of the bottom bracket. The frame’s reach is the difference between the two measurements. (See illustration to the left.)

You also can measure all of your body’s touch points on the complete bike in the same manner relative to the bottom bracket: “Seat Stack,” “Seat Reach,” “Bar Stack,” and “Bar Reach” (or, for bikes with aero bars, “Elbow Pad Stack,” “Elbow Pad Reach,” “Shifter Stack” and “Shifter Reach” — to the center of the shifter pivot). Stack and reach makes it easy to transfer measurements from one bike to another to set them up identically. But there’s more.

The reason I’m suggesting accessible stack and reach data for the new year is that if you had it for all frames on the market, you could easily determine which frames will “fit” you based on the stack and reach dimensions of your touch points.

The biggest drawback of current stack and reach frame sizing is that the effective head tube height varies due to headset type. If the frame has an integrated headset, it will have effectively about 2cm less stack than a frame with the same stack measurement with a standard headset. This is why I think that stack (and reach) would be measured to the headset upper bearing cover, rather than to the top of the head tube. As long as we’re resolved to go to the stack and reach system, why don’t we make this change, too? That way, we can start with a new, clean frame measurement system without a fudge factor in it.

Admittedly, I can’t tell somebody that I ride a 636/439 road frame, a 630/441 cyclocross frame, a 655/434 track frame for our steep, short indoor track here in Boulder, and a 653/449 mountain bike frame without feeling compelled to launch into a long explanation. But since we all got used to saying things like, “I ride a 56cm frame,” or even, “I ride a 56cm frame with a 56.5cm top tube,” and understanding conceptually what it means, perspicacity with this measurement system could come with familiarity, too. It will take consistency on the part of bike manufacturers in specifying it on every bike so that it becomes part of the cycling vernacular, though. And let’s include the headset while we’re at it.

Resolution for Fork Manufacturers: Provide a Hole in the Fork Crown on Forks with Cantilever Bosses

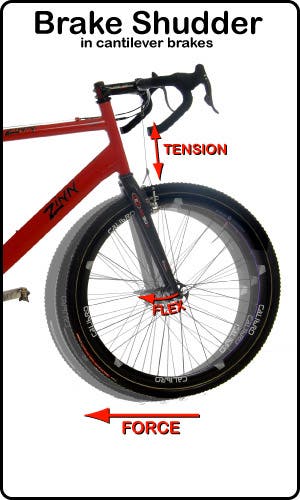

Brake shudder with cantilever brakes is caused by the fact that the cable hanger is attached above the head tube, and using a cable hanger that bolts onto the fork crown usually prevents it.

If the distance from the cantilever posts to the attachment point of the cable hanger above the headset increases in front due to the steering tube, crown, and upper part of the fork legs bowing as the fork flexes backward due to application of the brake, the front brake cable will become tighter. This will squeeze the pads harder against the rim, even if you are trying to modulate the pressure with your hand on the lever. If the tire does not slip on the ground, and if you don’t flip over the handlebar, then the wheel will be forced to rotate, momentarily breaking free of the pads, followed by being grabbed again by the pads, then grabbed harder by the pads due to the bowing in the upper part of the fork tightening the cable, etc. This is brake shudder.

A simple fix is to bolt a cable hanger onto the fork crown (thus eliminating the flexing steering tube from the equation), but there must be a hole in the crown to do it. A consumer drilling a hole in the crown, especially on a carbon fork, will probably void the warranty. If fork manufacturers simply provided the hole, all would be good. Some companies, like Trek, already make a crown-mounted cable hanger a standard feature on cyclocross and hybrid bikes.

Resolution (a Pipe Dream) for Component Makers: Compatibility

VeloNews’ senior online editor, Charles Pelkey, has a bike with frictional down tube shifters. He cares not whether the wheel has 5-, 6-, 7-, 8-, 9-, 10-, or 11-speed cogset on it; his derailleur will shift on any of them. Similarly, he can have one, two, three, maybe even four chainrings in front and his left shift lever will cover the range.

Trouble is, of course, that the shifting is not the crisp, exact shifting we’ve become accustomed to. Therein lies the rub, and why compatibility is a pipe dream. I don’t want to give up the performance that system integration has brought, but I also don’t like what we give up in order to have that shifting performance.

A lot of the people who would love to have and can actually afford the premium road bikes on the market cannot handle the gear range that’s available on them and still be able to go on their dream rides in the mountains or even in hilly urban environments. It wasn’t ideal and the parts didn’t all match, but there was a time when we could simply combine high-end road and mountain-bike drivetrain components and offer a low gear of, say, 22 X 32 to somebody who was carrying too much weight, too many years, or some other physical hindrance that prevented them from getting up a steep hill in a gear higher than that. That is no longer the case.

Shimano 9-speed road and mountain-bike shifters and derailleurs used to be cross-compatible. But Shimano 10-speed road shifters and 10-speed mountain-bike derailleurs are completely incompatible. So much for the guy who wants that 22 X 32 low gear on a lightweight, top-end road bike.

SRAM 9-speed road and mountain-bike derailleurs and shifters used to be completely incompatible. But now, SRAM 10-speed road and mountain-bike components are completely compatible. That’s great news, right? Well, it would be if SRAM made a left lever that could shift a triple. So what are you going to do if that 34 X 32 low gear of the Apex compact double group is not enough? Give the rider a Shimano or Campagnolo left triple lever with a SRAM right lever when they are vastly different in shape and aesthetics?

And what about Campagnolo? The customer needing this super-low gear wants and can afford the nicest stuff, which is 11-speed, but there’s no triple option with that. And even switching to the Campy out-of-series 10-speed triple option does not provide any lower than a 30 X 29 low gear, much less an integrated-spindle crank or carbon cranks or derailleurs.

So, this one will stay a pipe dream, but, boy, simply providing one additional component here or there within one of these “systems” could make a bunch of people very happy, from the rider to the bike dealer.

Happy New Year.

— Lennard