Commentary: Building a cycling union, straight from Miller's mouth

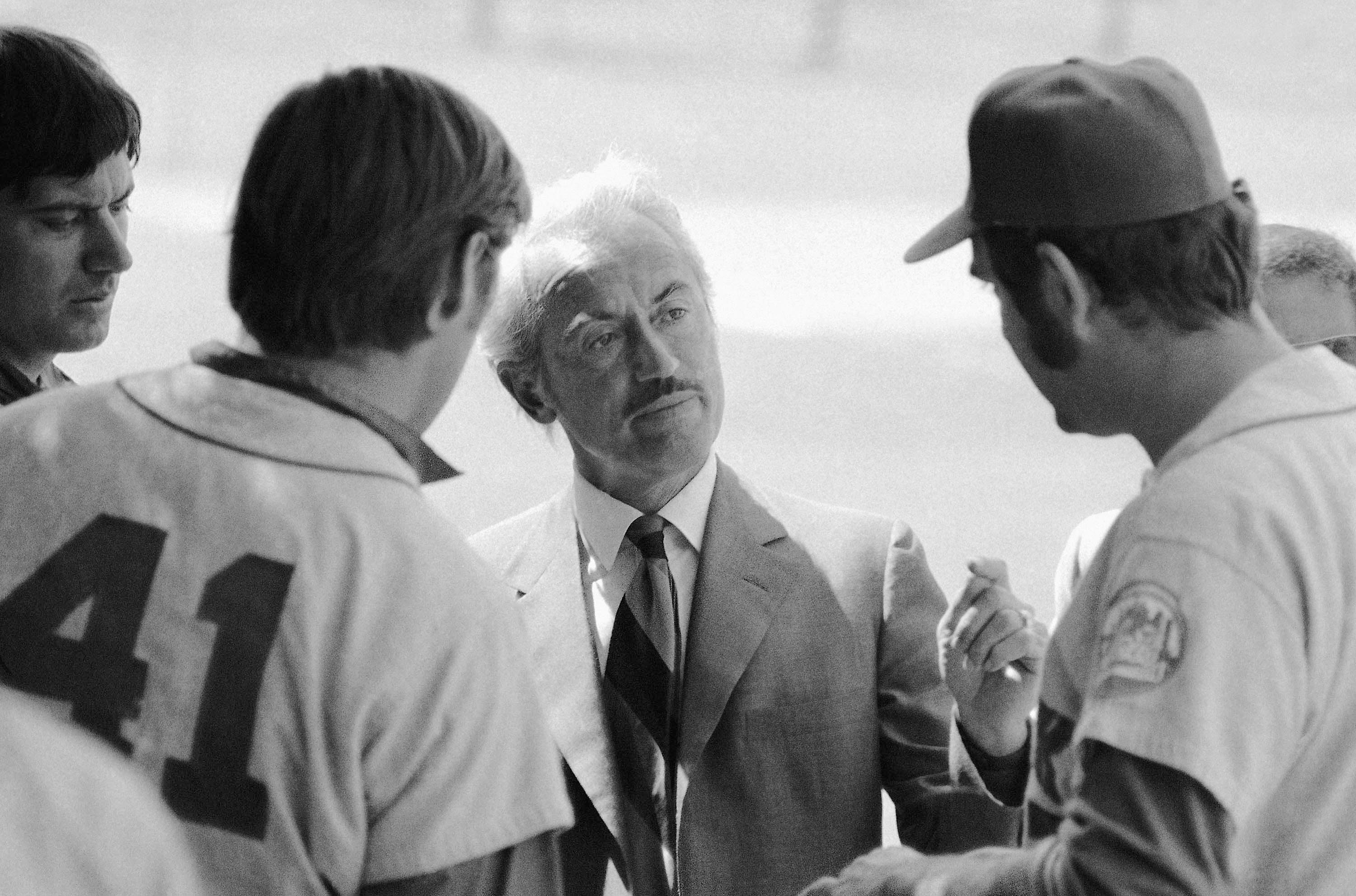

Marvin Miller was largely responsible for building the baseball players' union and his efforts provide guidelines for cycling's professionals. AP Photo

Editor’s note: As we ring out 2012, we look at 12 of our favorite stories of the year. Mark Johnson’s wide-ranging interview with former baseball players’ union chief Marvin Miller and his commentary on building a professional cycling union first appeared in August. Miller died on November 27 at the age of 95.

Shortly after my opinion piece on pro cycling and Marvin Miller ran on VeloNews.com this month, I received an email from his daughter, Susan Miller. Her father had read the piece, liked it, and wanted to talk.

Soon, I’m on the phone with Marvin himself, the labor leader and economist whose mobilization of baseball players in the 1960s and 1970s revolutionized the business of baseball. The hour-long conversation ranged from the genesis of Miller’s game-changing role in Major League Baseball to doping in sport and provided a number of lessons as riders and teams attempt to organize themselves more strategically in our own sport.

A phone call

“Could you speak up just a little louder?” Miller asks. At 95 years old, his hearing is not what it used to be.

Miller starts by explaining why, in 1965, he was inspired to step away from his role in organizing steelworkers to lead pro athletes.

With big labor unions, “you didn’t have that personal relationship because it was just too big,” he says. He elucidates, spelling out the numbers with a precision suggesting Miller’s keen interest in the minutiae of business: “When I left the steelworkers for example, they had a million, two-hundred and forty-nine thousand members. And you couldn’t get to know them if you lived to be a thousand.”

“I wanted an opportunity to start something from scratch,” he says. To organize a small group of players (about 600 in 1965; 1,300 today), was an opportunity for Miller to work face-to face with those he represented.

The comment is telling, since today’s pro cyclists point to their sheer numbers and global dispersion as one reason it is difficult to organize. Yet, today’s 900 top-level pro riders are few compared to the organizations Miller left. Working with a small group of athletes “was a powerful factor that made the offer of the job very interesting to me,” Miller recalls.

Another challenge that keeps pro cyclists from organizing is that the sport takes a short-term view. Sponsors and rider contracts are fleeting. Races appear and disappear. Riders’ livelihoods are tenuous, which makes it difficult to convince them to make short-term sacrifices to realize the long-term rewards of solidarity.

As Thor Hushovd told me in 2011 when I described Marvin Miller to the Norwegian star, if the riders were to demand a share of profit or not ride, “maybe we lose six months of racing.” Speculating about what might happen under the steady hand of a Miller-like figure, Hushovd says the riders never try the experiment because “nobody wants to lose one race.”

“That was difficult,” Miller says of his initial efforts at getting the players to look beyond immediate losses to larger, long-term benefits. “But the exploitation was so great that once they began to understand that no one was doing them any favors,” their attitudes began to change.

“They were the game,” Miller points out. This is a reality that is also the case today in pro cycling, where the stars are the race, not the organizer nor the governing body.

Of the players, Miller says he “found that while they were really beginners at trade unionism and understanding it, they were among the fastest learners I had ever met.” Once the athletes grasped the gulf between their pay and their actual market value, Miller says painful awareness of their exploitation propelled them past trepidations about the short-term sacrifices of a strike.

Topps turning point

Miller cites the contract that Topps, a baseball card manufacturer, had players sign while they were still in the minor leagues: five dollars for five years of rights to their images.

“Five bucks!” Miller exclaims, his voice still shaking with astonishment at the rawness of the deal. He used this crummy contract, which all the players signed, as an educational tool.

He recalls telling the players that the thrill of appearing on the same bubble gum cards they cherished as kids blinded them to being taken advantage of. When Miller explained that their sense of awe was “part of the exploitation, and how much money Topps and other companies were making off their willingness to sign up and give these companies the right to their picture, they understood.”

The analog here is not a reach: every pro dreams of racing the Tour de France. Once that opportunity is there, it would seem madness to strike at that honor, even if today’s riders, like yesterday’s baseball players, are getting a raw deal.

“We started a boycott of Topps,” Miller recalls. And in short order the company was forced to improve the terms of its licensing contract. “It was a great experience” for the players, Miller notes. “They saw what solidarity could do.”

When Miller first approached Topps to discuss “a realistic contract that would pay the players an appropriate amount,” he was dismissed in much the same way Jonathan Vaughters was when he proposed television revenue sharing with Tour de France owner Amaury Sport Organisation.

Chuckling, Miller recalls that Topps’ company president “came to my office and he heard me out.” The novelty card executive then laid out the facts for Miller: “Look I understand what you are saying, but I don’t see your muscle.”

Miller reported the conversation back to the players and they initiated a policy of no players signing any new contracts with Topps.

Suddenly bereft of rookie playing cards and stars that would not renew their expiring agreements, Miller says the Topps president phoned him for another meeting. He came in, Miller recalls with a laugh, and “the first thing he said was, ‘I see your muscle.’”

Topps negotiated a new contract that “in a very short time was netting the players roughly $50,000 a year. It was a great experiment and a great lesson in what solidarity and organization could do.”

Miller calls the Topps agreement “a monument” that marked the beginning of an era when the athletes finally understood how their collective force, when focused on a specific goal, could yield returns that were unimaginable over the previous century.

Miller also says his role was that of a teacher and listener — a catalyst for change that equipped athletes with knowledge. Miller notes that it was the players’ collective sense of drive that was key to their progress, not Miller himself. “I tried to be careful,” he says. “I didn’t want a cult of people thinking that I was doing all this.”

Motivated by results

When discussing the organization of baseball players and the ensuing baseball business model revolution as an analog for pro cycling, Miller brings up a telling point: athletes are profoundly motivated by results. Seeing the tangible results of the Topps standoff and subsequent negotiations, the players became more convinced of the efficacy of organization. “They could see the results,” Miller recollects. “And results are important.”

In 1965, baseball, like pro cycling today, stumbled along with a lopsided business structure that benefited organizers but not performers. And in 1965, both the baseball team owners and the league’s commissioner cried that changing it would end the sport for good.

“I’m telling you, it came about rapidly,” Miller says of the reforms that took place once the players showed some muscle. “Before I’d been there six months.”

If today’s pro riders asked Miller to help them organize, how would he start? By repeating what he did with baseball players, he says.

“We got to have some understanding of how [the business] works and then we got to have unity in the ranks and we’ve got to be determined. And at times we have to be willing to make temporary sacrifices because the gains to be made are tremendous,” he says. “That’s where you begin.”

On sports doping

When it comes to how baseball has managed doping, Miller is unrepentant because he is skeptical about the efficacy of doping. Today he would still reject the commissioner of baseball’s 1985 proposed that the players submit to random drug testing.

According to Miller, that’s mainly because he doesn’t “pretend to know whether steroids for example are a magic potion that increases your ability to engage in professional sports.” And, he argues, “nobody knows, and I don’t believe you can proceed with an intelligent policy without the scientific facts that make you know. So I wouldn’t change anything that was done back then.”

With police sirens ringing outside Miller’s New York apartment, I ask Miller if he has followed the Lance Armstrong cases. “Yes,” he says, ”from a distance.”

Miller’s thoughts reveal how his decades of labor experience — sometimes wrestling with the highest levels of executive, judicial, and legislative power — have made him deeply skeptical about politicians that try to force labor unions to implement drug laws the government can’t enforce itself.

With Armstrong, Miller opines, “What you are seeing is policy being run not on the basis of fact, not on the basis of scientific knowledge, but on the basis of self interest of people who have made a career of so-called anti-doping and the people who have invested in laboratories of their own to make a profit out of this whole thing.

“It’s really absurd to give it the kind of standing and credibility that a large part of the media has done. That’s a damaging thing that the media has done.”

More than economics

When I ask Miller whether he saw the baseball players’ plight as one of economic or human injustice, he responds that, “it was both.” And, he points out, framing the issue as one of both human and economic rights is the best way to forward a labor group’s point of view with the public. “It can’t be economics alone,” he says.

When considering how a balancing of power in cycling might affect those that currently corner that power — namely the ASO — Miller says “the baseball experience is something that has not been given its proper due.”

Miller points out that player salaries and benefits have grown tremendously since unionization. The minimum player salary in 1965 was $6,000 (roughly $43,000 when adjusted for inflation). Today it is $480,000. Average salaries have grown from $44,676 in 1975 to $3.1 million in 2011.

But the attendant growth of the larger baseball industry “is even more remarkable.”

“When the union started, the combined revenue of the industry was less than $50 million a year. That’s million with an M. Last year it was seven billion. That’s billion with a B,” says Miller.

Because of the overall growth of the game precipitated by unionization, Miller says the team owners “have far more dollars to pay all their costs, plus more profits than they ever have had before.”

Miller tells me that when the baseball players began pushing for a bigger share of the baseball pie, the team owners cried poverty and argued that higher salaries and benefits would bankrupt the game. However, the teams refused to prove that point, and like the ASO, kept their ledger shut.

“They eventually caved on the question of what was secret and what was not,” Miller explains. “Because we began to threaten them with unfair labor practice charges which they desperately wanted to avoid.”

Once the teams began to reveal their enormous revenues, poverty became a bogus platform for argument, and the players gained both more credibility and leverage over the game that they made happen.

Could a pro cycling leader pull off a similar balancing coup with the ASO? And how about with the UCI in terms of demanding more transparency and consistent enforcement of its technical and doping rules?

Time will dictate, but Miller says that leader needs a certain skill set. The first tool is experience. “I had been active with trade unions all my life,” Miller says of his life before baseball. Said leader would want “a lot of experience to fall back on.”

He also cites “the personal touch” as a key quality for a sports labor leader. “The knowledge of what your membership was feeling and what they were thinking and what they wanted,” says Miller.

Finally, cycling’s Marvin Miller must be both a tireless student and a teacher. “You wanted [the athletes] to learn from the get-go what a trade union was and how it operated,” he says. “And the way to do it was to study and understand the nature of the industry they were in.”

Beyond that, Miller says patience and repetition are essential while “people absorb information and begin to learn to the point where you can just exult that you had a membership that had a large cadre of activists who understood better than the owners how the industry operated and how badly they have been exploited.”