Explainer: Why canceling pro races could help curb the spread of coronavirus

KUURNE, BELGIUM - MARCH 01: Start / Kuurne City / Fans / Public / Peloton / during the 72nd Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne 2020 a 201km race from Kuurne to Kuurne / #KBK20 / @KuurneBxlKuurne / KBK / on March 01, 2020 in Kuurne, Belgium. (Photo by Tim de Waele/Getty Images)

The recent news that Strade Bianche and the Sea Otter Classic among other races have been either postponed or canceled due to the global coronavirus outbreak has understandably seized control of the cycling world’s collective focus.

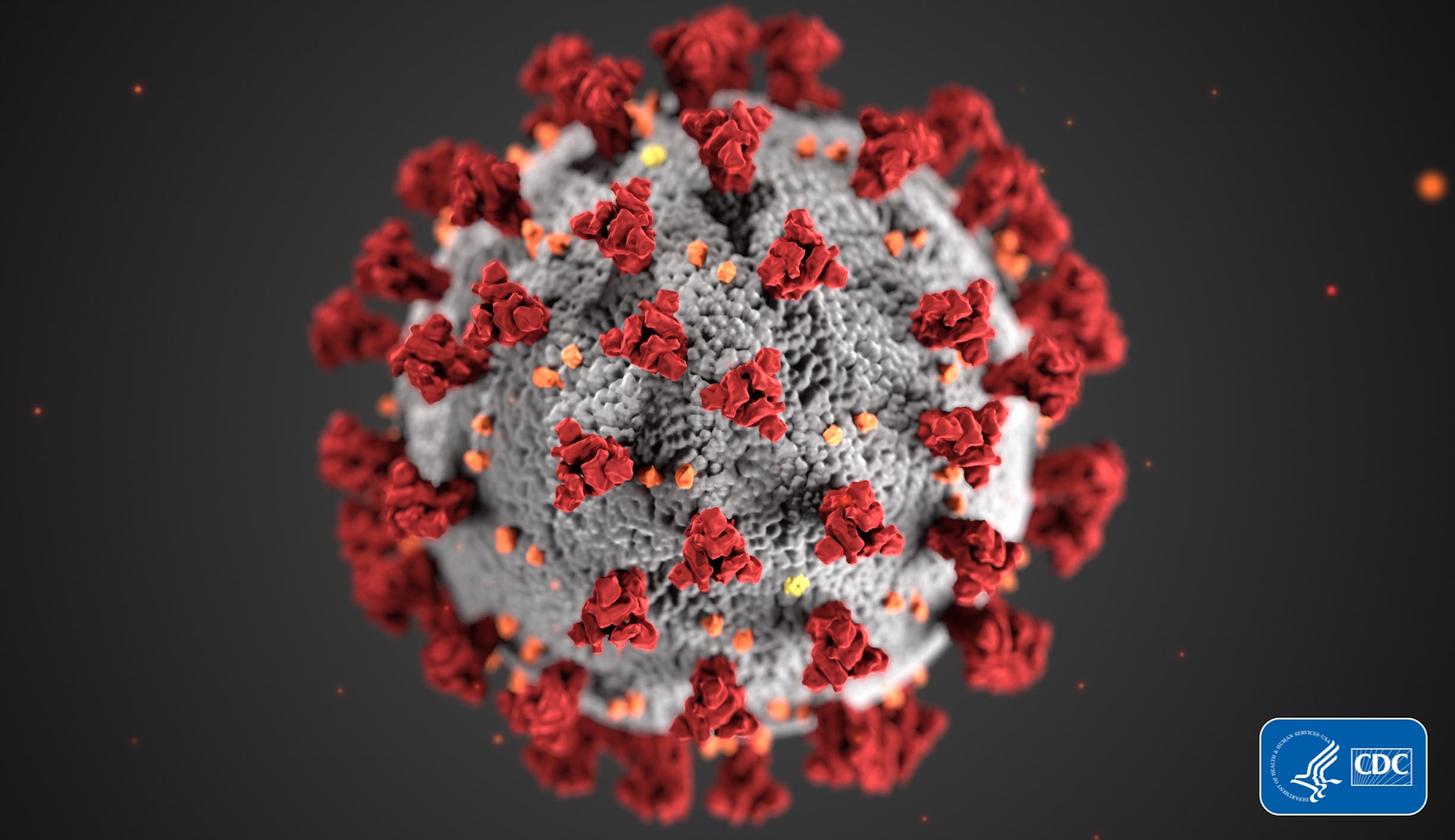

While many questions about the virus called COVID-19 remain unanswered, the medical and scientific community agree that keeping people separated from one another helps control the spread of transmissible diseases. Thus, the rash of cancelled cycling events over the past week illustrates that race promoters are responding appropriately.

VeloNews spoke with Amie Meditz, Infectious Diseases physician at Boulder Community Health in Colorado to discuss commonly-asked questions about the virus and its implications in the cycling world right now. Meditz has worked on outbreaks of respiratory illnesses in hospitals and specialty clinics throughout her career.

Why should cycling events be cancelled?

“Social distancing is a proven public health method for preventing the spread of communicable diseases,” Meditz says.

Especially in the case of a new virus, when there are still unknowns about its behavior, separating people who may be infected from those who are not prevents further spread of infection. This is particularly relevant at a spectator-heavy cycling event, where people stand shoulder-to-shoulder for long periods of time and share common spaces like bathrooms and eateries.

“In close proximity situations like this, we’re worried about inhalation,” Meditz says. “What if someone coughs or sneezes in a crowd? People are also going to be touching the same surfaces.”

At a race like Saturday’s cancelled Strade Bianchi, numbers could tally close to one hundred thousand spectators. Given what specialists know about communicable disease transmission, the public health implications of preventing a gathering that size are clear.

“There’s enough concern right now to try and contain it at this level so it doesn’t become an even bigger problem,” Meditz says. “We know that this [social distancing] works, so that’s what people are using to keep this from becoming an even bigger problem.”

For race organizers who are trying to plan for events that may be weeks or months out, Meditz suggests conservative caution.

“For us, as an institution, it’s somewhat of a day-by-day thing, but in the short term we’re trying to avoid large groupings of people for things that are not essential.”

How is COVID-19 actually transmitted?

Transmission of the virus occurs when the respiratory droplets of an infected person are either inhaled by or introduced to the mucosal membranes of an uninfected person. What does this look like to the average person?

“These droplets are the things you can actually see on a surface when you sneeze or cough,” Meditz says. “Some are perceptible, some are smaller than we can perceive, but it’s those actual droplets that come from the nose and mouth when we’re coughing.”

When those droplets land on the surfaces and objects around us and we touch them and then touch our faces, the virus can enter through mucosal membranes in the eyes, mouth, and nose. More rarely, a person could contract the virus by inhaling the droplets of someone in close proximity – between 3-6 feet – who sneezes or coughs.

“That’s where the hand washing comes in,” says Meditz. “And not touching your face, avoiding people who are sick. It’s also why people who are sick should wear masks.”

Not enough studies have been conducted to determine how long COVID-19 can survive out of the body on a surface; however, Meditz says, if it was compared to a similar virus like “the typical circulating coronavirus that causes a common cold,” it could live anywhere from a few hours to several days.

How long is someone contagious?

Due to the lack of scientific data about the virus’ behavior, there is no clear consensus on the exact period of contagiousness. According to Meditz, public health entities like the WHO are giving this period a wide range of one to 14 days in the hopes of capturing people before they go out and potentially transmit the virus.

“We really don’t know how long someone is contagious,” Meditz says, “but what we’re seeing is that most people are getting sick 4-7 days after exposure, so we’re thinking that a week after that someone might not be contagious.”

What’s most important in terms of contagiousness, she warns, is that it’s a moving target.

“It has to do with understanding the number of people who were really infected, and we don’t know that.”

Right now, the estimates are that for every one person infected, another one to three will also get infected. With influenza, the conversion rate is just slightly lower; for every one infection, there will be one or two more infections. Nevertheless, Meditz says, this number will likely be adjusted since there are people missing from the count.

“I like to compare it to the measles,” she says. “For every one person infected, up to 18 could get infected.”

What does COVID-19 infection look like in a healthy person?

While we know that at least six riders in the pro peloton have tested positive for COVID-19, media requests for updates on their health have been denied. According to Meditz, unless these athletes have severe, underlying medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, the illness from infection is likely inconsequential.

“Most people have a very mild illness,” she says.

As of now, the only groups of people who are known to have worse outcomes from COVID-19 infection are older individuals, and people with underlying medical problems. This has been proven in various microcosms during this outbreak. In terms of professional athletes and whether the physiological stress of intense exercise puts them at an increased risk, Meditz says that their fitness actually puts them at an advantage in terms of recovery.

“In my general practice of infectious diseases, I don’t consider elite athletes to be immunocompromised,” she says. “Of course, really healthy people can get really sick. But in the case that a professional athlete has become seriously ill, they usually do better.”

As long as they remain in quarantine with very little outside impact, the riders from teams that still remain in quarantine on Yas Island in the UAE are safe, says Meditz. If one person started going out, hanging out at the hotel bar and got infected, the risk for the entire group would go up significantly.

“Based on cruise ship data about 20 percent of the team might get infected in those close quarters,” she says, “But if everyone stays together, even riding a bike race with no spectators or outside people, it would be pretty safe.”

What can everyone do to stay safe?

Given what health officials know about the spread of COVID-19, the decision to cancel some of cycling’s most prestigious spring races is the right one. Since most people will not know they’re infected, preventing their co-mingling with others is a sure way to reduce transmission rates. As for the rest of us? It’s not rocket science.

“Carry hand sanitizer and don’t touch your face,” Meditz says.

People also have to change their thinking about feeling “so-so” and still going to work or other public places, she says. Working remotely and skipping out on non-essential social gathering are two easy ways to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or any illness for that matter, when you’re not sure if you have the infection.

“If you’re not high risk, don’t feel short of breath, and don’t have a high, persistent fever, then stay at home,” Meditz says. “If you do think you need to go to the emergency room or urgent care, call ahead so staff can prepare.”

As for the common misconception that the virus will die off with the onset of warmer temperatures, Meditz believes this to be a misconception.

“It has nothing to do with warmth, it has to do with winter where more people are inside grouped together,” Meditz says. “It has to do with transmission modalities, and there are more opportunities for transmission in winter.”

Whatever the weather, spectator-heavy cycling events present an opportunity for transmission and are thus being cancelled appropriately.