From the pages of Velo: Britain takes center stage

Velo Magazine, March 2012. Photos: Graham Watson; Harry How, Bryn Lennon, Carl De Souza | Getty

Editor’s Note: The following cover story appeared in the March 2012 issue of Velo Magazine. For more on the London Olympics, visit our Olympics landing page.

Before voting began at the International Olympic Committee meeting in Singapore six years ago, London was considered an outsider to host the 2012 Games. But after four rounds of tight voting against the likes of Madrid, Moscow, New York and Paris, London came out on top by a dramatic 54-50 margin over Paris. The French were stunned.

Three years later, in Beijing, the world was stunned when British cyclists won eight Olympic gold medals — twice the number they’d taken in the previous 100 years. The experts said that one nation so dominating the cycling events was a feat unlikely to be repeated in a modern Olympiad — but for a country that shocked the world in Singapore and again in Beijing, who would bet against four-time Olympic champ Sir Christopher Hoy and his British team equaling, or even topping, its 2008 medal haul before home crowds?

An Auspicious Beginning

British cycling was at low ebb in 1948 when the Olympics last came to London, at the so-called Austerity Games. London was recovering from World War II, with the populace still subject to food rationing, so there were no resources for new sports facilities. The Olympic road race was held on a circuit in Windsor Great Park, and the four track events were raced at the Herne Hill Velodrome, built in 1891.

Remarkably, the modest Great Britain cycling team earned medals in all five Olympic events: silvers for Reg Harris in the sprint and tandem sprint (raced with Alan Bannister), a team silver in the road race (for Bob Maitland, Ian Scott and Tiny Thomas), and bronzes for Tommy Godwin in the kilometer time trial and 4km team pursuit (with Wilfred Waters, Dave Ricketts and Bob Geldard).

The team’s stars, Harris and Maitland, are no longer with us, but Godwin is an ambassador for this year’s London Games. Before one recent television preview, Godwin rode his 1948 Olympic track bike around the Herne Hill track and showed off the white, knitted-wool Great Britain team jersey he wore 64 years ago.

Godwin, British Cycling’s first national coach, clearly remembered the enthusiasm generated by his bronze-medal rides. “It was unbelievable,” he told the BBC. “The crowd was fantastic. After we won the race for the bronze medal in the team pursuit, a cycling magazine reported, ‘There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.’”

Godwin is fully expected to be “in the house” at the state-of-the-art, $152 million London velodrome when Britain’s track racers seek more gold medals later this year. As it happens, the only track event that remains from the previous London Games is the team pursuit. “Back then, we were complete amateurs,” recalled Godwin, who worked in a factory when he won his two bronze medals. “We raced for clocks and medals. Now, they earn thousands of pounds every time they put their leg over a bike.”

Bradley Wiggins has been a sponsored athlete on the British national team since he was 18 and he earned Olympic team pursuit medals in 2000, 2004 and 2008. This year, his focus is on the Tour de France, which ends six days before the July 28 Olympic road race — but he’ll also be standing by to ride the team pursuit in case of an emergency.

The pursuit squad trains at the Manchester Velodrome, which is also the headquarters of British Cycling, where the federation’s performance director and Team Sky general manager Dave Brailsford has his office. The boss likes to keep an eye on his charges, as he did at the track team’s December boot camp, where pursuit coach Dan Hunt worked his riders as much as seven hours a day at the velodrome, with motor-paced sessions and full-out drills in team pursuit formation. Other days saw the riders training on the hilly roads of the nearby Peak District or undergoing speed work on the track.

Hunt and his riders know that their likely rivals in August — Australia, New Zealand and Russia — are doing similar preparation. Russia has revived its pursuiting traditions under new German coach Heiko Salzwedel, who previously coached the Australian, Danish and British teams to world and Olympic successes. Anchored by longtime road racer Alexei Markov, the Russians took silver at the 2011 track worlds and, in round one of this winter’s UCI Track World Cup, clocked a world-class time of 3:56.127.

Back in 1948, when Godwin raced, the Olympic record in the team pursuit stood at 4:41.4. Sixty years later, the gold-medal British team of Ed Clancy, Paul Manning, Geraint Thomas and Wiggins set the current world record of 3:53.314 in Beijing. That’s an average speed of 61.179 kph, but the British coaches believe that the winning team in London will have to approach 63 kph, perhaps breaching the 3:50 barrier.

Clancy and Thomas are favored to again lead the four-man British squad, with likely support from two younger men on Sky’s ProTeam roster, Peter Kennaugh (pronounced “Kenn-ock”) and Ben Swift, while newcomer Andre Tennant and Wiggins will be standing by. After winning the individual pursuit title in Athens and Beijing, Wiggins talked about scoring an Olympic hat trick in the city where he grew up, but the individual pursuit was infamously dropped from the Olympic schedule by the UCI two years ago so that the 10 track races could be evenly divided between men and women (see Track, page 31).

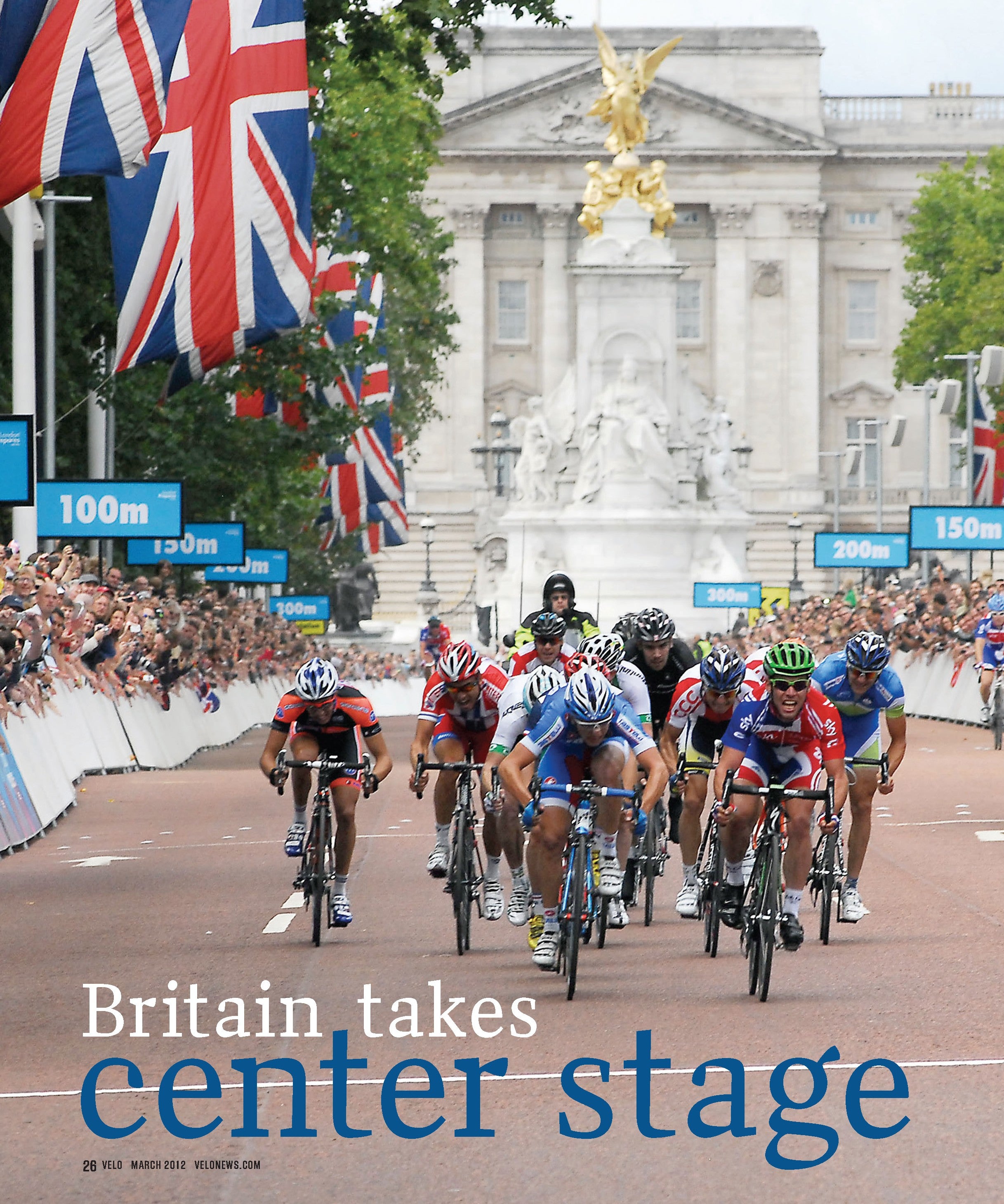

Instead, Wiggins will focus on the road time trial, which takes place before the track events and four days after the opening day’s road race. “Cycling is going to be the major sport in London,” predicted UCI president Pat McQuaid. “Like Beijing, the road race will showcase the city, with the start and finish at Buckingham Palace.”

McQuaid actually helped choose the course for the road races through the southwest London suburbs, passing the historic Hampton Court Palace on its way to the Surrey countryside and multiple laps around a challenging 9.7-mile (15.5km) circuit at Box Hill before returning to the city center. McQuaid knows the area’s roads well, having ridden them as an amateur cyclist while he studied for a degree in physical education at St. Mary’s University College, which is just down the road from Hampton Court.

Beijing began the “tradition” of showcasing the Olympic hosts with a course that started near the Forbidden City and ended on a loop traversing the Great Wall of China. The huge difference between that road race and London’s will be the crowds. Security in Beijing was such that spectators were physically stopped from lining the finishing circuit, whereas London may see a repeat of the Tour de France’s grand départ in 2007, when an estimated four million fans witnessed the opening stages.

The casual fans this year are all expecting Britain’s most popular sportsman, Mark Cavendish, to win the elite men’s gold medal — given his 2011 world title, Tour green jersey and last August’s victory in the test event on the Olympic course. But there will be three big differences with this year’s race. It will cover nine laps of the Box Hill circuit (rather than just two in the test event), increasing the distance from 87 to 155 miles (250km); the full field of 145 riders will feature all of the world’s best classics riders and sprinters; and the major teams will be only five riders strong, and without race radios.

Commenting on the course after the test event, Brailsford said, “It’s a heavy sort of road surface in places and the circuit is definitely not to be underestimated. It gives you very little time for recovery.”

The British official’s fear is that, over nine laps, the race will split apart on the Zig Zag Road climb up Box Hill and his team won’t have the strength to keep Cavendish with the leaders in the 50km run-in to the London finish. “Cavendish will have to be in the shape of his life,” Brailsford added. “I would say that riding and finishing the Tour de France would be a big part of [his] preparation.”

Cavendish knows that, especially as the Tour finishes in Paris only six days before the Olympic road race. At the Tour, expect to see Cavendish working harder on the hills, and should he be dropped on a hilly stage, expect him to get his new Sky teammates to pace him back to the peloton before a sprint finish.

There’s been talk that Wiggins might not be able to fully support Cavendish in the Olympic road race, as he did so outstandingly in Copenhagen, because his main event, the time trial, is only four days later. But all of the TT riders (one per country) have to race the road race first; and because Fabian Cancellara will again likely be shooting at medals in both events (as he did in Beijing), and world TT champ Tony Martin will probably play the “Wiggins role” for his German teammate André Greipel, all these TT contenders will also have to be motivated for the road race.

There’s a chance that Britain could win gold in both the road race (Cavendish) and TT (Wiggins), while the British women are also medal contenders in both events. Another home gold could come in BMX competition, but the burden of living up to the media and public expectations remains in the velodrome.

“I don’t think that we will ever be able to replicate what we did in Beijing,” Wiggins said. “It’s not a case of having to do better than we did last time. Things have changed.”

The three-time Olympic champion was referring to the major changes in the track schedule, which have eliminated two of Britain’s gold-medal events, the men’s and women’s individual pursuit, and replaced them with the six-event omnium for both categories. But with three medal events for sprinters (team sprint, match sprint and Keirin) of both sexes, and with defending sprint champions Hoy and Victoria Pendleton still on top form for Britain, an eventual eight-gold bounty for the home team is again possible.

As Britain’s Olympic ambassador Godwin said, “The 2012 Olympics, I think, are going to be absolutely wonderful.”

Road Race

The course for the two road races is very different from that of a conventional Olympics or world championships. Instead of multiple laps of a circuit at the end, the laps are done in the middle of the race, followed by some 50km of racing before the finish. At 250km, the men’s race resembles a spring classic, most notably Belgium’s Ghent-Wevelgem.

Huge crowds are expected on the 15.5km Olympic road circuit near Dorking after an initial section through the Surrey hills. The main climb to the top of Box Hill, overlooking the green, rolling terrain of The Weald, is similar to those in the Belgian classics: it averages 5-percent grade on a narrow road featuring two sharp switchbacks (giving the road its name, Zig Zag), rising just over 400 feet in 2.5km (similar to Mont Cassel). Nine times up Box Hill (twice for the women), combined with the bumpy nature of the circuit’s country lanes, very narrow in places, is sure to split the race apart — and only the best-prepared sprinters will stand a chance of staying at the front.

The finish is on The Mall, the regal boulevard leading from Buckingham Palace, where Fabian Cancellara famously won the prologue time trial of the 2007 Tour de France. And it should give rise to a sprint similar to the one Mark Cavendish and his rivals will likely experience on the Champs-Élysées the previous weekend at the end of this year’s Tour.

Besides Cavendish, the men most likely to contest gold in the men’s race are Cancellara, Tyler Farrar of the U.S., Oscar Freire of Spain, Philippe Gilbert of Belgium, Matt Goss of Australia, André Greipel of Germany and Thor Hushovd of Norway.

Britain has three potential winners in the women’s 140km race — defending champion Nicole Cooke, sprinter Lizzie Armitstead and 2010 world time trial champion Emma Pooley — but there’s a risk of disharmony within the team following the 2011 worlds road race. Cooke placed fourth in Copenhagen, while Armitstead crashed just before the sprint and still came in seventh in the bunch gallop.

A few weeks later, Armitstead told Cycling Weekly, “Cooke rode for herself in my opinion. I’ve never seen her work for a teammate… it’s been an unspoken situation for too long.” Cooke has denied her teammate’s claim, but the spat might well resurface at the Olympics where last year’s worlds medalists, Giorgia Bronzini of Italy, Marianne Vos of the Netherlands and Ina Teutenberg of Germany, will be ready to capitalize on any mistakes by the home team.

An American Sprinter in London

Farrar’s take on the Olympic road race

With its nine laps over Box Hill, followed by a 50km run-in to the finish on The Mall in central London, the men’s Olympic road race course is one of the most interesting routes in recent memory — made all the more interesting given the fact that each nation’s five-man team will not use race radios. Will sprinters like Mark Cavendish, Matt Goss and André Greipel be dropped on Box Hill, and if so, will the race come back together before the finish line? Or will fast-finishing power riders like Philippe Gilbert and Thor Hushovd fight to keep the race separated to the line? We asked American sprinter Tyler Farrar how he sees the race playing out, and what that might mean for him. At the test event last summer, Farrar was tangled up in a late-race crash and was unable to contest the sprint, won by Cavendish.

“It’s an interesting course,” Farrar said. “The run out to the circuit and run back in are really easy, fairly straight, flat roads; it’s 50km each way. The circuit itself is a lot harder than people have been giving it credit for. It’s pretty nasty. In the test event, we only did two laps. When you have to do nine laps in the Olympics, that’s really going to wear on people.

“The climb is longer than I was led to believe before I saw it. There’s no recovery on the circuit — left-right, updown, small roads. If it was a regular WorldTour race, with eight-rider teams and race radio, it would be one thing, but with five-man teams in the Olympics and no race radio, I think it’s going to break up a lot on the circuit. It will be hard to reorganize things, with only five riders and a lack of communication. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I think it will break up, so the question is whether it will come back together on that 50km run back into London.

Time Trial

For the nation that invented the individual time trial, it’s appropriate that a major portion of the Olympic time trial course is along the Portsmouth Road, a stretch of highway that saw thousands of amateur riders compete in traditional, early-morning TTs through the 20th century. And before competitive time-trialing began, between the 1870s and 1920s, it was the most famous cycling route in Britain, when hundreds would cycle the 25 miles from London to Ripley for Sunday lunch at the famed Anchor Inn (which is still in business).

The cycling heritage gains extra traction through Brad Wiggins, a Londoner and a favorite for the elite men’s TT gold in August, who also happens to be the current national 10-mile TT champion as recognized by the 90-year-old Road Time Trials Council (now called Cycling Time Trials).

The Olympic TT course starts on the driveway to the 600-year-old Hampton Court Palace, about 12 miles southwest of downtown London. In revealing the course last March, chief executive of Historic Royal Palaces, Michael Day, said, “Since Henry VIII’s time, the palace has played host to many great sporting occasions such as jousting, wrestling, archery and fencing. We are thrilled this sporting legacy will continue in 2012.”

The men’s 44km course first crosses the River Thames and makes a short loop to the west around the reservoirs before heading south on the main, counterclockwise circuit, which turns at the town of Cobham before heading northeast on the old Portsmouth Road through Esher to Kingston-upon-Thames. It re-crosses the river to make a loop to the north, past McQuaid’s alma mater and back through Bushy Park, where kings of England once hunted deer, to the finish at Hampton Court.

The women’s 29km course doesn’t include the initial loop, nor the final one, heading straight to the finish line from Kingston. In both events, riders will start at 90-second intervals.

Only one or two riders per nation can start in the Olympic time trials (depending on 2011 world TT championship results) , so competition will be intense for those spots, particularly among the Americans. Beijing bronze medalist Levi Leipheimer has to show the selectors that he’ll be better suited to the rolling course than multi-national champ Dave Zabriskie, while the much younger Taylor Phinney and Andrew Talansky have to improve on their showings at the 2011 worlds if they are to be considered.

There should be no selection problems for Switzerland’s defending Olympic champion Fabian Cancellara (who has already scouted the course with his new trade team manager Johan Bruyneel) or Germany’s current world champ Tony Martin — both of whom will be using the Tour de France as preparation for London. Other potential contenders include Richie Porte or Jack Bobridge of Australia, Gustav Larsson of Sweden, Jesse Sergent of New Zealand and Svein Tuft of Canada. Wiggins is the logical representative for Britain, but it’s possible he could have competition from Sky teammate Chris Froome.

On the women’s side, 2008 gold medalist Kristin Armstrong first has to win her place on the U.S. team over another former world champion, Amber Neben, before defending her title. And once selected, the best American will face stiff competition from the past two world champions Judith Arndt of Germany and Emma Pooley of Britain, along with Linda Villumsen of New Zealand and either Tara Whitten or Clara Hughes of Canada.

Mountain Bike

The British don’t hold out much hope of gold medals in the two cross-country races because the home country’s best mountain bikers are downhillers, which is not an Olympic event. However, the organizers (after several attempts) have come up with an exciting course in the rolling hills at Hadleigh Farm, Essex, overlooking the Thames Estuary, 40 miles east of London. It includes a couple of technical rock sections, made with imported boulders, which were added to the difficulties before the Olympic test event last July.

There were limited fields for both men’s and women’s races on a day of warm sunshine, but there were two strong winners. The men’s 2004 and 2008 Olympic champ Julien Absalon of France won comfortably ahead of runner-up Christoph Sauser of Switzerland, while Canada’s Catharine Pendrel — who went on to take the 2011 world championship — rode away from her regular Luna teammate Georgia Gould after the American crashed on the last of six laps.

Maybe Absalon, the highest paid cyclist in France, and Pendrel will again take gold this coming August; but the opposition will be much tougher. In the men’s race, Absalon will have stiff competition from new world champ Jaroslav Kulhavy of the Czech Republic and former world champions Nino Schurter of Switzerland and José Antonio Hermida of Spain. Todd Wells, who placed top-10 at the 2011 worlds, will likely be the strongest U.S. challenger for a medal.

Pendrel’s winning experience on the Olympic course could well give her the edge in August, though she’ll face a fierce challenge from Poland’s Maja Wloszczowska, who took the Olympic silver in 2008, was world champion in 2010 and runner-up to Pendrel at last year’s worlds.

BMX

The Brits fully expect that one of their sporting heroines, Shanaze Reade (a five-time world champion with three BMX titles and two team sprint titles on the track), will snag a gold medal in London. But after Reade easily won the Olympic test event last August, she criticized the 450-meter-long BMX track that starts atop a 25-foot-high structure next to the new velodrome in London’s Olympic Park.

“I’m happy with the win,” she told the BBC, “but for the females the track is on the limit when the wind changes… there’s a little work to be done.” Others said the course could “get ugly” on a windy day (more likely to blow the lighter-built women on the many jumps), and that seemed to be confirmed when current world women’s champion, Mariana Pajón of Colombia, crashed heavily and had to be stretchered away.

Assuming the problems are sorted out by this August, Reade, 23, and Pajón, 19, look set for an epic battle. Pajón will be in her first Olympics after years of dominating world junior competition. Reade was close to winning at her first Olympics four years ago, challenging eventual French gold medalist Anne-Caroline Chausson in the final turn, when the tall Brit touched wheels with the multiple-time world downhill champ and crashed out.

Crashes were also a problem in Beijing for American BMX star Mike Day, who eventually took the silver medal in the men’s final behind Latvian Maris Strombergs. Day, now 27, should again be battling Strombergs along with the winner of the London test event last August, Marc Willers of New Zealand.

Track

The 6,000-seat velodrome was the first of the new structures to be completed at the Olympic Park in the East End of London last February, but it won’t be used in competition until a year later (February 16-19) at the finale of the 2011-12 UCI Track World Cup. One reason for the delay was that the contractors didn’t hand over the whole project until late 2011, but it has the upside of allowing the Siberian pine track surface to dry out and probably fulfill the organizers’ prediction that it will be the world’s fastest. Controlled temperature and humidity will also help that goal.

Britain’s reigning Olympic champions Chris Hoy, Victoria Pendleton and Jason Kenny have all ridden the track, and Hoy noted that the “wraparound” seating will help create a better atmosphere for the riders and the fans that will pack the stadium every day. “Instead of having the back straight and home straight as you go around,” he said, “you get this wall of noise the whole way. It creates this gladiatorial arena. All of the Union Jacks will be out and, hopefully, the noise and the atmosphere will give us an advantage, maybe put the fear of death into the other countries.”

Hoy is hoping that the home support will help him retain his titles in the match sprint, Keirin and team sprint (with Kenny and probably Jason Queally), the only men’s events (along with the team pursuit) that are retained from Beijing.

The races that have been controversially axed — the individual pursuit, Madison and points races — have been replaced by the six-event omnium that will be contested over four sessions in two days. It’s being billed as cycling’s equivalent of the decathlon, but that track & field event has a sophisticated points system that rewards the performance differentials in individual disciplines whereas cycling’s equivalent has a simplistic one point for a win, two for second, et cetera, which rewards the most consistent (and blandest?) performer rather than the most outstanding athlete.

The omnium (modified last year) is now made up of three time trials (a one-lap flying start 250 meters, a full-distance 4km pursuit and a traditional 1km TT) along with a 30km points race, a 15km scratch race and an elimination (or miss-and-out) event.

The likely British challenger in the omnium is team pursuiter Ed Clancy, who won the world title when it consisted of just five events in 2010, while Phinney (third that year) could be the American challenger, should he not gain the road time trial selection.

The women have lost both the individual pursuit and points race from Beijing, but gain the team sprint (Britain is favored), team pursuit (Britain, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. are all contenders), Keirin and omnium as Olympic medal events.