How Remco Evenepoel, Egan Bernal, and other Generation Z riders are changing pro cycling

SAN SEBASTIAN, SPAIN - AUGUST 03: Remco Evenepoel of Belgium and Team Deceuninck-QuickStep / Fans / Public / during the 39th Clásica Ciclista San Sebastián 2019 a 227,3km race from Donostia-San Sebastián to Donostia-San Sebastián / #Klasikoa / @dklasikoa / on August 03, 2019 in San Sebastian, Spain. (Photo by David Ramos/Getty Images)

This story appeared in the September/October issue of VeloNews Magazine.

Something extraordinary happened in the final hour of racing on the twisting roads of northern Spain in early August. Remco Evenepoel, the swashbuckling 19-year-old Belgian phenomenon, rode everyone off his wheel on the final climb at Clásica San Sebastián.

Despite a chase from some of the biggest motors in the international peloton, including Olympic champion Greg Van Avermaet and world champion Alejandro Valverde, Evenepoel tearfully crossed the line all alone, more than 30 seconds ahead of the charging group.

The victory was as emphatic as it was astonishing. Not only did it make Evenepoel the youngest winner ever of a major one-day race in the modern era, it put a punctuation mark on a trend that is quickly reassembling the power structure and hierarchy within the peloton.

More than a coming-of-age moment, Evenepoel’s victory was a declaration of a new era.

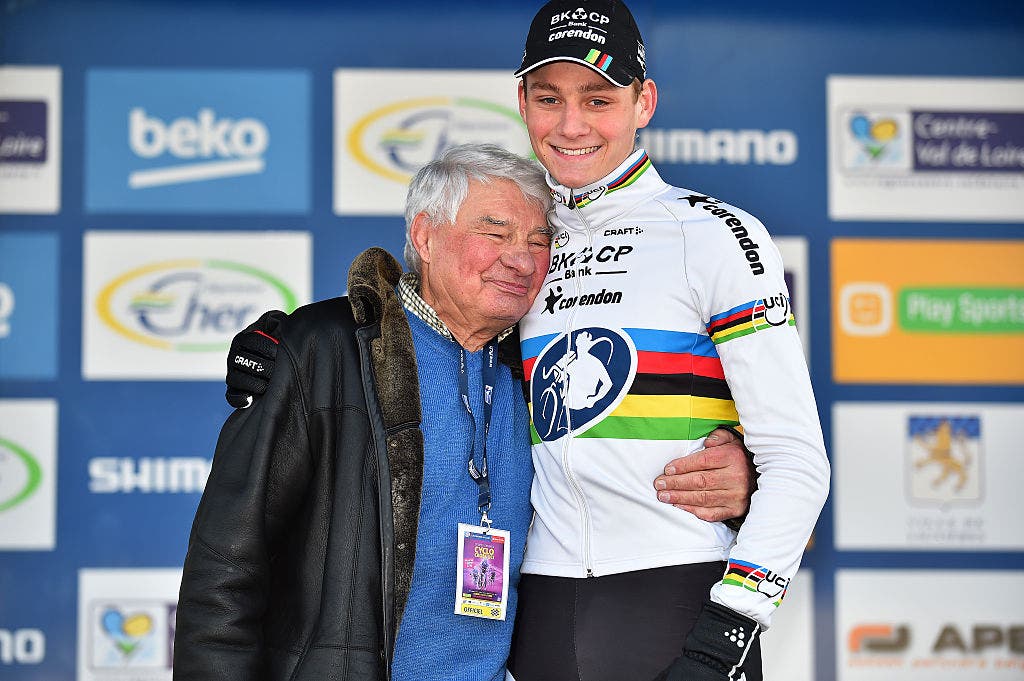

“This is exceptional,” said Eddy Merckx. “We know that Remco has a large engine. The fact that he is already showing it proves that he is mature early. He is ready for the big job. Can he follow in my footsteps? Maybe he will even get better. Remco has all the qualities to make it happen.”

Evenepoel’s emancipation came a week after Egan Bernal pedaled into cycling nirvana, breaking the barrier to become the first Latin American to win the Tour de France, and becoming the youngest winner, at 22, since World War II.

Behind them is an equally magnificent cadre of incredibly talented and ambitious young riders—all of them under 25, and some, like Evenepoel, still in their teens—who are posting promising results and rewriting the script of professional racing.

“They keep getting younger and they keep getting faster,” said veteran pro Rory Sutherland (UAE-Emirates), 37. “The things these young pros are doing now I could not imagine when I came up. It’s impressive how successful they’re becoming.”

These are not Millennials. The famous so-called “Class of 1990”—which includes the likes of Nairo Quintana, Peter Sagan, and Romain Bardet—seems like yesterday’s news.

The leading lights of today were all born in the late 1990s. Or, in Evenepoel’s case, in 2000. The prodigiously talented Belgian is the first WorldTour winner born in this century.

The riders of Generation Z are here, and they’re suddenly making an impact in every race they start.

The focus on young talent

Cycling’s history is full of riders who make immediate and dramatic imprints in their rookie seasons. Eddy Merckx won the first of his record seven Milano-Sanremo victories at the age of 20. Greg LeMond finished third in his Tour de France debut at 23, and won two years later. And even the controversial Lance Armstrong won the world title at 21, still the youngest ever to earn the rainbow stripes.

Most of them were like comets across the night sky—that rare, freakishly great cyclist who could dominate a generation.

Things seem different this time.

Behind Bernal and Evenepoel, this season has seen a core group of young racers suddenly pressing to the fore. Pavel Sivakov (Ineos), winner of the Baby Giro in 2017, won his first WorldTour stage race barely a month after his 22nd birthday when he captured the Tour of Poland in August. The 22-year-old David Gaudu, France’s highly touted Tour de l’Avenir winner in 2016, had a break-out Tour riding in support of Thibaut Pinot for Groupama-FDJ. At 20, the U23 world champion Marc Hirshi (Sunweb) is banging on the door of his first WorldTour win.

There’s an undeniable surge of youth within the peloton. It isn’t just one exceptional young rider, but a swarm.

Of Deceuninck-Quick-Step’s 27-man roster, 10 are under 25. The team has been on the forefront of nurturing talent. Its now-defunct Klein Constantia Continental team, which folded in 2016, produced such riders as Enric Mas, Ivan Cortina, Jhonatan Narváez, Maximilian Schachmann, and Rémi Cavagna. All of them are now WorldTour pros in their early 20s.

“The future of the sport is in young cyclists,” said Deceuninck-Quick-Step boss Patrick Lefevere. “When I came up, there was not much attention paid to developing young talent. They were often neglected in favor of the big champions of the day. I wanted to change that when I became a sport director.”

UAE-Emirates is also investing in a youth movement. The team signed Jasper Philipsen, 21, another highly touted Belgian who already has one WorldTour win in his rookie season. Tadej Pogačar, the 2018 l’Avenir winner, became the youngest WorldTour stage-race winner at the age of 20, after coming out on top at the Amgen Tour of California in May. Similar to Bernal’s five-year deal with Ineos, Pogačar is under contract with UAE through the end of 2023.

Perhaps it’s no mistake that Joxean Matxin Fernández, now lead sport director at UAE-Emirates, was a talent scout for Lefevere and Klein Constantia.

“There have always been good riders coming up,” Fernández said. “The big difference today is that a lot more teams are investing in young riders and in developing talent. Before you had to prove yourself to get a contract. Now teams give riders a chance to grow.”

What’s more impressive is the depth and quality of performances that today’s young riders have been able to deliver. It’s not as if they’re winning a stage at a second-tier event. They’re taking home the biggest trophies on the calendar.

Dutch fans are still talking about what they witnessed this spring: 24-year-old Mathieu van der Poel, born in 1995, emerged as one of the most dynamic and multi-faceted riders in the last half century. He bulldozed his way across the spring classics in a string of inspiring performances that was Merckxian on any level—winning four of the seven one-day races he started in March and April.

And then there’s Bernal, who is riding to heights unimagined when he joined Team Sky at the start of the 2018 season. Everyone knew he was good, but what he’s been able to realize in the first 18 months of his WorldTour racing career—winning Colombia Oro y Paz and the Amgen Tour of California in 2018, and Paris-Nice, the Tour de Suisse, and the Tour de France in 2019—is beyond words.

“The future is his,” Valverde said. “What he did last year was already impressive, but to win the Tour at 22 is something quite impressive. Let’s hope it’s not for the next 10 years, because it could get quite boring for the rest of us.”

Born to win

What do all these riders have in common? And how could they achieve so much so soon? Other than being fast and young, there are some interesting threads and commonalities.

First off, many of today’s new stars have the right DNA. Quite literally, they were born to race. Bernal’s father, though never a pro, was a top-rated amateur in Colombia, and gifted his son with his legendary VO2max that dips into the low 90s.

Sivakov’s dad, Alexei, was a Russian émigré-turned-pro who raced in Italy and France from 1996 to 2005, including three editions of the Tour de France. His mother,

Aleksandra Koliaseva, was a Russian national road race champion, and winner of the Tour l’Aude.

Of course, van der Poel’s DNA is almost an unfair advantage. His father was Adri van der Poel, a fabled pro with a nearly 20-year career who won such races as Tour of Flanders and Liège-Bastogne-Liège. His grandfather is French legend Raymond Poulidor, whose career stretched across cycling’s glory days from Jacques Anquetil to Merckx. When Mathieu matched his father to win the Amstel Gold Race in thrilling fashion in April, it seemed to announce the dawning of a new era in the peloton.

Many of today’s most astonishingly successful young riders also have unbridled ambition. Some of the older riders have grumbled out loud that today’s newer generation has no respect for some of cycling’s long-held traditions. Long gone are the days of a patron patrolling the peloton. Bernard Hinault would be aghast at the uppity nerve at today’s want-it-now ethos. The young guns simply do not want to wait their turn.

Of course, no one is going to win a race if they’re waiting their turn. Sagan certainly didn’t, and van der Poel won’t be taking his number in the classics next spring.

Another key factor is that today’s riders are at the cutting edge of the incremental advances that have steadily improved human performance over the past 20 years.

Better science, nutrition, and technology, which helps any bike racer, only acts as an accelerant when applied to today’s über-talented youngsters. Lighter frames, aero helmets and skin-suits, calibrated diets and recovery, coupled with the granular attention to detail in training programs means young riders can advance their racing development at a staggering rate. If they have the motor, and the skills to back it up, they can expect to perform almost immediately.

Team Ineos astutely signed Bernal and Sivakov, and counts nine riders who are 24 or younger on its 29-rider roster. Ineos has been on a recruiting campaign the past two years to bolster its aging line of confirmed leaders.

“We focused on recruiting a team of ‘young guns,’ many of whom rode the Giro this year,” said Ineos principal Dave Brailsford. “It’s exciting to help them develop and grow while also having the ‘A’ team continuing to push their performance at the highest level.”

Finally, many insiders cite a cleaner peloton for helping to clear the path for young talent to shine. The fact that a 22-year-old can win the Tour is viewed by many as a sign that cycling has leveled the playing field dramatically since the days of a peloton at two speeds.

The world’s blossoming talent pool has delivered a Colombian, a Russian raised in France, a Belgian, and a Dutchman of royal pedigree, revealing the peloton’s ever-larger international reach.

And it’s not just coincidental that the top young riders end up on the top teams. There is a methodology to talent-hunting. Sports directors, agents, and team managers scour the results sheets of the U23 races. The Tour de l’Avenir is the cycling equivalent to the NFL combine. A strong showing at the world championships in the U23 ranks can mean a phone call, a tryout as a stagiaire, or, if you’re really good, a contract.

Jumbo-Lotto is the poster child for how to build a WorldTour team in the 21st century: drive the tent poles around a few veteran anchors, like Steven Kruijswijk and Robert Gesink, and fill out the flanks with young talent. More than a quarter of its roster of 28 is 24 or younger, including Americans Sepp Kuss, 24, and Neilson Powless, 22 (Powless signed with EF Education First after this story went to print).

The team’s methodical approach to racing has nurtured such riders as Dylan Groenewegen and Primoz Roglic, and now they deliver at the highest level.

“Our philosophy is to take young riders and develop them slowly,” said team manager Richard Plugge. “It’s a different mentality than some teams. We like riders to ‘grow up’ with us and feel a bit like a family.”

Cycling, in its purest form, is inclusionary and ruthlessly democratic. If you’re fast and can stay upright, you will rise to the top.

Opportunities given to the young

Still, that doesn’t fully explain why these young riders have been so successful so early, and so often.

In many ways, today’s generation is the peloton’s disruptor. Today, Bernal, van der Poel, and those like them, look poised to turn cycling on its head. It’s too early to say how far this vanguard can go, but early indications suggest they could rewrite how we view modern cycling.

Just look at van der Poel: He’s not content to race “just” on the road. Van der Poel is gleefully embracing the various roots and branches of modern cycling. It’s no longer only about the Tour de France. Performance and greatness can be measured not just in results, but in engagements, in interfacing with fans, and with the pure joy of racing.

Perhaps van der Poel’s biggest challenge, much like Sagan’s before him, is to stay engaged and motivated (i.e. to not get bored) with the intensity and demands of performance at the highest level of road racing. That’s one reason why van der Poel, led by his father Adri and backed by a multi-year deal with Canyon bicycles, is creating a multi-discipline platform on which his prodigious son can perform.

He’s already world champion in cyclocross, and is emerging as a dominant force in mountain biking. (He’s won three of six rounds of the XCO World Cup series.) This spring was just a taste of what lies ahead on the road for van der Poel, but first he’ll target the Olympic gold medal in mountain biking in Tokyo.

“His main goal now through next year is the Olympics, and after that, we’ll sit together and talk about the future,” Adri said. “What he did [during the classics] is a lot about character. He’s a rider who only rides to win races.”

Indeed, burnout may be the biggest hindrance to this brave new wave of riders hitting the sport. Cycling is riddled with young, gifted riders who shone brightly. A few years ago, Andrew Talansky emerged as America’s best grand tour hope in a generation, only to completely abandon the sport just as fast. Nairo Quintana, at 29, already seems past his prime after flying so close to the sun in his early 20s.

The demands and sacrifices required today are unlike any in the sport’s history. Some riders at the apex of the sport, like Marcel Kittel or Peter Kennaugh, simply walked away when they couldn’t manage it.

Teams are not shy about pushing the drill, however, when it comes to tapping into the mineshaft of young talent.

Dating back more than a decade, top WorldTour squads fully embraced the youth movement. Part of it was to clean out some of the lingering vestiges from the EPO era. Another factor is simply financial. With the top stars earning millions or more per year, teams need to fill out their rosters with what they have left over. Young riders come relatively cheap.

Teams are also willing to throw out the script when it comes to nurturing and developing these young talents.

Jumbo-Lotto, for example, wasted no time bringing Wout Van Aert to the Tour de France this year. The 24-year-old is a few years older than the likes of Evenepoel, who still isn’t old enough to order a beer in the U.S., but the Belgian is just as fresh to the road scene.

The three-time cyclocross world champion made an immediate impact on the road, underscored by his sensational debut in 2018 in the northern classics. A move to the WorldTour this season included the promise of racing the Tour. Jumbo-Lotto held up its end of the bargain, and Van Aert repaid them with a stage win and a decisive performance in the team’s TTT victory in stage 2.

“We give every rider a chance to perform at a certain point of the season,” Jumbo-Lotto’s Plugge said. “Too often young promising riders become workers, and they lose that winning instinct. We like to see all of our riders race to win at a few points of the year.”

The arrival of these young prodigious riders is disrupting the traditional inner workings of teams at another level. Team Ineos brought Bernal to the Tour last year even though he had never raced more than eight days in a row up to that point. Why? The numbers proved it. Within a year, he vaulted ahead of his more established teammates, stars like Wout Poels and Michal Kwiatkowski, in the team’s pecking order. By 2019, they were working for him at the Tour.

Bernal could have never made history this summer if Brailsford had followed the customary approach for developing young riders. Rather than ship him off to the Giro d’Italia or Vuelta a España to learn the craft, as the traditional method calls for, Brailsford took the risk to take Bernal to the Tour last year. That bet hit paydirt less than 12 months later.

“At 33, 34, Geraint and Chris are coming to the twilight of their careers,” Brailsford said during the Tour. “I wanted a ‘new’ Chris Froome, basically. So I set myself the challenge of finding him. I took two years looking at all the younger riders and liked the look of Egan. I had to wait a year, and then managed to negotiate him out of his contract.”

The same nonconformist approach goes for Evenepoel. After he ripped through the junior world championships last year, winning both the road race and time trial titles, he catapulted straight to the WorldTour, and bypassed the U23 ranks altogether. For now, his team is holding him back, and promising it will be two seasons before he makes a grand tour debut in 2021.

“My only job with a rider as good as Remco is not to mess it up,” said Quick-Step’s Lefevere. “I have seen many good young riders go too fast too soon. He is too young to race the Tour de France [in 2020]. We must give him space to move, but also not throw a wrench in the wheel.”

A perfect time for Generation Z

The flood of young, charismatic talent certainly comes at a good time for the sport.

Many of today’s biggest stars, such as Froome, Geraint Thomas, Van Avermaet, and Philippe Gilbert, are all well into their 30s. Or, as is the case with Valverde, nearly 40.

And though Team Sky and Froome ascended as the most dominant force in cycling over the past decade, the team’s PR foibles coupled with Froome’s Boy Scout good manners have never truly captured the collective imagination of the larger cycling public. Bad-boy Bradley Wiggins flamed out before he could truly hit superstar status, and many of the sport’s other icons, from Alberto Contador to Tom Boonen, are retired. Sagan is today’s only genuine celebrity.

To attract a new generation of fans, professional racing needs young, exciting, charismatic riders. And suddenly the sport is overflowing with candidates to fill the void.

Bernal is poised to dominate the Tour de France unlike any rider in a generation. The mild-mannered Colombian has the skills, the temperament, the motor, and the team to potentially reel off one yellow jersey after another. Even Armstrong said Bernal could beat his redacted record of seven Tour titles.

More than anyone, van der Poel has all the makings of a true international superstar for a new age. The Dutch phenom is so talented he can dominate any discipline he chooses.

And then there’s Evenepoel. No rider has created such buzz as the Belgian teen. When Quick-Step held its annual training camp in January along Spain’s Mediterranean Coast, hundreds of journalists showed up. No one wanted to talk to Julian Alaphilippe or Philippe Gilbert. They were all there for Remco.

“We don’t know how far he can go, but everyone agrees he is a one-in-a-million talent,” said veteran Belgian journalist Hugo Coorevits. “The next Merckx? No, there is only one Merckx. He is the first Remco. We can be happy with that.”

The likes of Gilbert, Sagan, and Froome still have a lot of pavement in front of them, but everyone knows that the future is suddenly here.

The 2019 season will be remembered for a changing of the guard. The peloton’s next big disruption is already happening.