How a Strava KOM helped save Keegan Swirbul's pro career

Photo: João Fonseca

Every cyclist in Boulder, Colorado knows Super Flag.

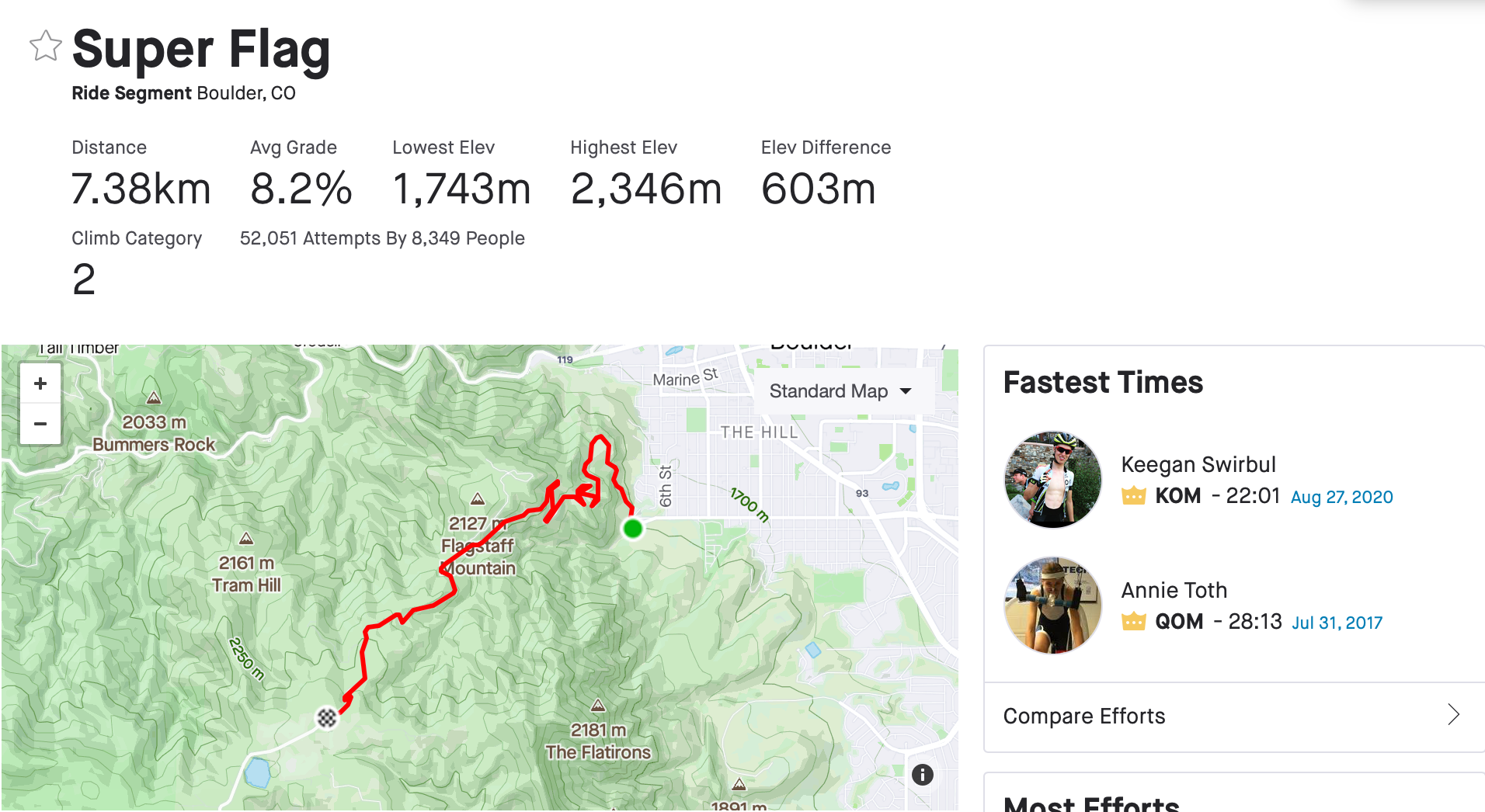

That’s the unofficial name for the most popular climb in town, a 4.58-mile slog up Flagstaff Mountain to a collection of mailboxes high above the city. The total ascent is 1,978 feet, the average gradient is 8.2 percent, with a two-tenths-of-a-mile section at 20 percent, known as ‘The Wall.’

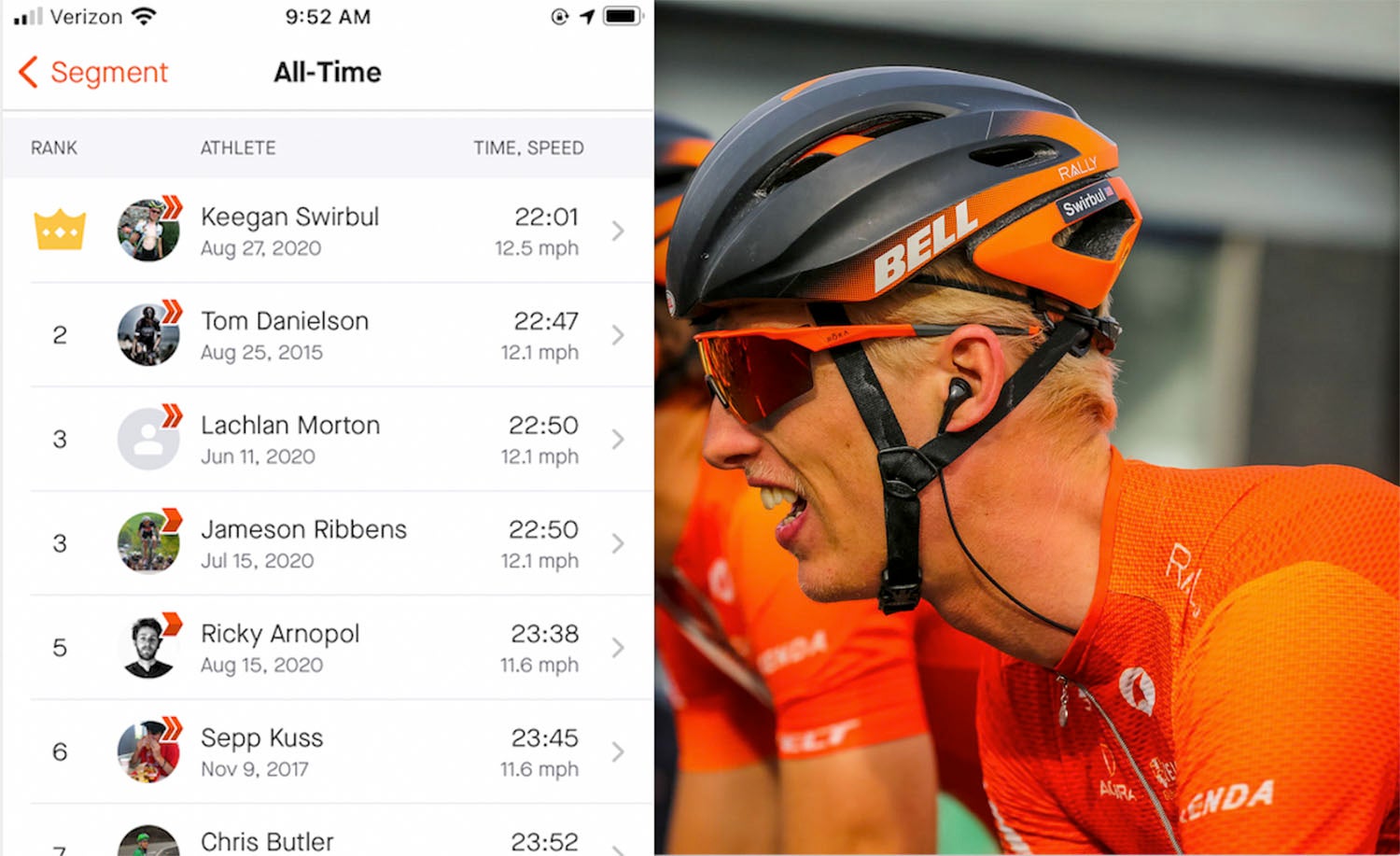

A quick glance at the climb’s statistics on Strava tells you whatever is left to know. More than 8,000 recorded attempts. Names on the top-10 leaderboard include Sepp Kuss, Ruth Winder, Lachlan Morton, Tom Danielson, and Erin Huck.

This past August, Keegan Swirbul smashed the five-year-old Strava record on Super Flag midway through a three-hour training ride. Then, the very next day, Swirbul came within four seconds of Levi Leipheimer’s KOM on the shorter Flagstaff Mountain segment, which Leipheimer set during stage 6 of the 2012 USA Pro Challenge.

The Strava accolades couldn’t have come at a better moment for Swirbul. Now, these two rides may likely mark a turning point in his young professional career.

“I love Strava and I’m completely obsessed,” Swirbul told VeloNews. “I’m not bragging about it to try and get on a team. But hey, it just came up casually.”

Wunderkind in waiting

Keegan Swirbul is hardly a newcomer to the U.S. cycling scene, and not long ago was the star climber of the U.S. development ranks. In 2015 he won the under-23 national road race title, and rubbed elbows with Tao Geoghegan Hart, Ruben Guerreiro, and Will Barta on Axel Merckx’s Axeon Cycling Team.

Those three eventually progressed to the WorldTour, while Swirbul’s career stagnated in the topsy-turvy U.S. domestic scene.

“I made a lot of dumb mistakes — being too motivated at times, not listening to people who were more experienced,” Swirbul said. “I had a lot of time when I was pretty overtrained, and it took me a while to even follow a coach’s plan.”

Swirbul’s early pro years coincided with the near collapse of the U.S. domestic road scene, as one by one, major races and prominent teams shuttered. In 2018 Swirbul was out of a job after his Jelly Belly/Maxxis folded. He received a lifeline from Floyd’s Pro Cycling, and in 2019 had his best year to date, finishing second overall at the Tour de Langkawi before attaining top-10 GC finishes at the Tour of the Gila, Tour de Beauce, and Tour of Utah. When Floyd’s pulled out at the end of that season, Swirbul was again unemployed.

“I emailed around to every team I could find,” Swirbul said. “I recognized that I needed to go to Europe full-time.”

One of the calls Swirbul made was to Jonas Carney, the longtime director of Rally Cycling. Rally was already staffed up for 2020, Carney said. Another email went to Ljubljana Gusto Santic, the Slovenian team that was once home to Tadej Pogačar. To Swirbul’s surprise, they gave him a job. All he needed to do was get himself to Europe.

And then, disaster struck.

During a January training ride in Scottsdale, Arizona, Swirbul sped into a blind corner on a bike path and struck a cyclist traveling the opposite direction who had veered into his lane. Both riders were taken away in ambulances, and Swirbul was diagnosed with a fractured vertebra. For three months he would need to wear a protective back brace, and riding outside was impossible.

“That’s when it all kind of crumbled. Once COVID hit and there was no racing, that was kind of the end of everything,” Swirbul said. “It was not an enjoyable time. I was just grinding on my trainer in my garage.”

The lookout for talent

Like all pro cycling teams, Rally Cycling was caught off-guard by the COVID-19 pandemic. The squad had enormous European ambitions for 2020, and in a matter of weeks, races like the Tour de Suisse were called off entirely. Most of Rally’s riders returned stateside from Europe to wait out the pandemic, and as the spring turned to summer, their return to the European theater seemed unlikely after the European Union banned most inbound American travelers.

“We had a hard time getting athletes back and forth to Europe,” Carney told VeloNews. “There was no easy answer.”

When racing started up again in early August the team had to get creative. For the five-day Le Tour de Savlie Mont Blanc it fielded a team of just five riders, one shy of a full roster. Two of the five riders were French neo-pro riders hired for the event. The lion’s share of the team’s riders were not able to travel.

As Rally dealt with its manpower issue, Swirbul was back on his bicycle, pedaling long and punishing miles near his home. He had no races to train for — the deal with Ljubljana Gusto Santic was put on ice amid the pandemic. Swirbul chased Strava KOMs, and chased all-day rides across the mountains. He piled on training volume he normally would never do.

“It’s like, let’s try to learn about my body, try more volume, and just learn without any fear of overdoing it,” he said. “I saw the summer as an opportunity to experiment with training methods that normally I’d be afraid to do.”

In early August Swirbul traveled to Boulder to bum around and ride his bike. He and a friend lived in an RV parked on the street near the base of Flagstaff Mountain. Swirbul knew the climb and its famous Strava times well. And, with his motivation and fitness at a peak, he set out to try and beat them.

“Ever since I started racing I was fascinated with Levi’s KOM from Gregory Canyon to Flagstaff — if you zoom out on the segment finder you can see that it’s one of those elite 10 or so KOMs in the entire country,” Swirbul said. “He got it during a race where he took the [leader’s] jersey. He was a huge rider back then. So, I figured that would be an untouchable one that I wanted to crack. It was in my mind all summer.”

Taming Super Flag

There was just one problem with Swirbul’s plan for Strava greatness: His bike. Swirbul still rode his old race bike from Floyd’s Pro Cycling, an aging Van Dessel, and by mid-2020 the bike had logged thousands of hard miles and was creaking with every pedal stroke.

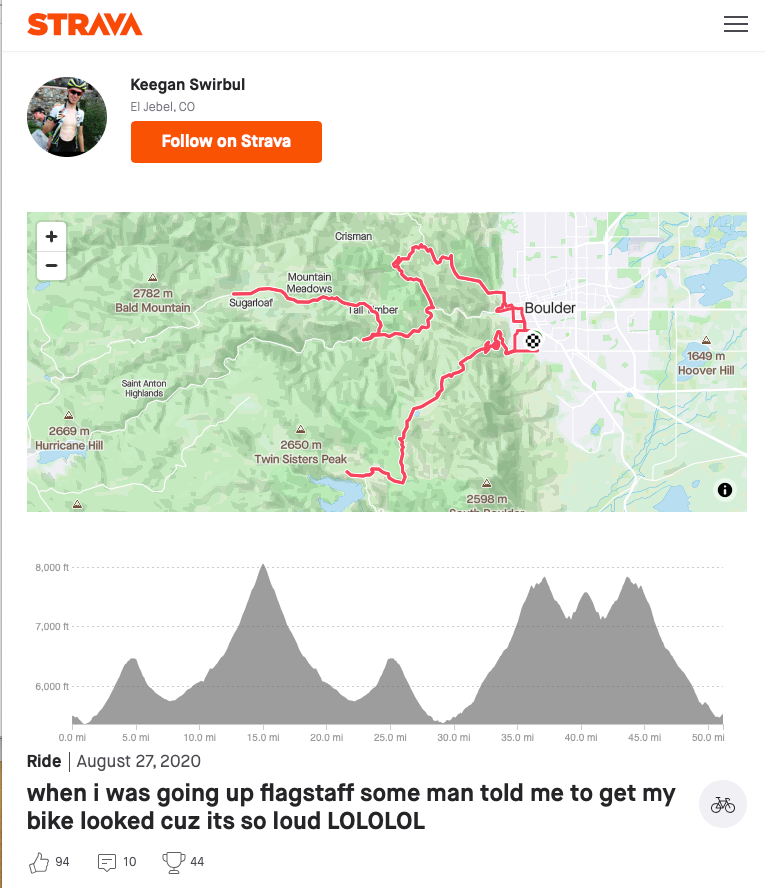

On August 27 Swirbul headed out for a climbing session on the aging bike and ascended Sunshine Canyon to Poorman Road, where he descended a dirt section and then climbed the long, steep Sugarloaf Road. After descending back to Boulder, Swirbul headed to Super Flag, for a planned 90-percent effort to the summit.

The lower section felt easy as he whirred the pedals over, speeding through the climb’s shallower first half. He pushed the pace through each steep switchback and then rested on the flatter sections between. Just past the turnoff to the Leipheimer KOM Swirbul upped the pace on the climb’s steeper sections. The bike’s creaking got louder as Swirbul pumped more watts into the frame.

“I passed some guy and he was like, ‘Your bike, sir! It doesn’t sound so hot!'” Swirbul said. “Something was really whacked-out inside the bottom bracket.”

Swibul upped his pace into the wall and then surged up the steep incline, rounding the final switchbacks to the mailboxes while maintaining his 90-percent effort. After topping out Swirbul kept going, riding to and from Gross Reservoir before descending back to his RV, unaware that he had just set the new fastest mark. It wasn’t until he uploaded the ride’s file that Swirbul saw the strength in his legs.

His final time: 22:01, 46 seconds faster than Danielson’s record from 2015.

“I didn’t know the time to beat on [Super Flag], so to see I got it was pretty cool,” Swirbul said.

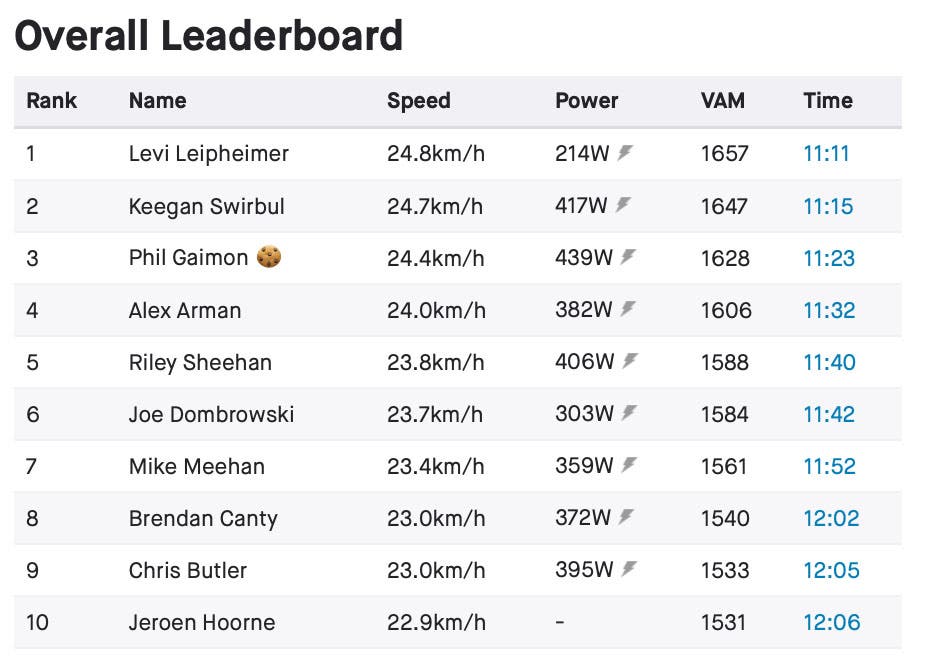

The KOM confirmed Swirbul’s fitness, and so the next day he targeted Leipheimer’s time on Flagstaff Mountain. After warming up on the climb Swirbul went max effort on the climb, a 2.87-mile ascent of 1,013 feet. Swirbul’s average power was 15 watts higher than the day before, and he rocketed up the climb at 15.3mph. Swirbul checked his final time at the top: 11:11. He had surpassed Phil Gaimon and Joe Dombrowski, but Leipheimer was still four seconds ahead.

“It was a bummer,” Swirbul said. “It was a childhood dream to get that one.”

From Strava to European racing

Jonas Carney was at his home in Golden, Colorado when he received an email from Swirbul. The youngster was asking to borrow a bicycle for training, as his rig had finally fallen apart after weeks of Strava chasing. Could Carney loan him one of Rally’s spare Felt racing bikes for more Strava records?

Carney felt sympathy for Swirbul — he had been on Rally’s radar for years and was one of the talented riders caught out by U.S. cycling’s tough labor situation.

“We were really close to bringing him on board for [2020] — I think he was the last guy left off,” Carney said. “He was still on my radar.”

The two met the next day. Carney marveled at the state of Swirbul’s training bicycle — the pedals barely turned over. Then, Swirbul told him the story of his Strava accolades earlier that week. Carney was amazed.

“The efforts he was he was recording and the bike he was doing it on was just ridiculous,” Carney said. “Levi’s record up Flagstaff was in a full-on racing situation, and [Swirbul] almost broke it on this dirty bike with heavy wheels with a pump and a tube under his seat. There was probably an extra pound of grit and grime on it.”

Carney knew Swirbul was a skilled road racer. He considered the Strava records, and then examined Swirbul’s training load. He considered his team’s manpower struggles in Europe. Swirbul owned a Slovenian racing license, and the document would allow him to travel overseas amid the pandemic.

“It wasn’t just the Strava stuff, it was that he had stayed that motivated and was training that he didn’t know if he would be racing,” Carney said. “It impressed me how badly he wanted it.”

Technically, the team was outside of the UCI window allowing a mid-season transfer. Carney emailed the UCI to see if he could get an extension to add a rider. The UCI would allow it, so long as the rider was added as a ‘stagiaire‘ status. Carney reached out to Swirbul with an offer. The team was taking on two climbing races in Portugal — was he interested?

“I couldn’t believe it,” Swirbul said. “The whole summer I had somewhat of a hope that I’d end up racing my bike, and by that point, I had basically given up on it. I was super happy.”

Back on track

Swirbul was one of Rally’s top performers at both the GP Internacional Torres Vedras and Volta a Portugal races. At Torres Vedras, he finished 9th place overall, one spot behind the team’s GC leader, Gavin Mannion. In the latter race, a punishing eight-day stage race, Swirbul became the team’s GC leader after Mannion faltered. Swirbul’s results were impressive, and it was his attitude behind the scenes that truly impressed Carney.

“To be in the top-10 in your first race back after a year without racing is pretty impressive,” Carney said. “I got a lot of good feedback from the athletes and the staff. At some point, he’s just checking all of the boxes.”

After the racing block, Carney offered Swirbul a contract for 2021 and 2022. After years of uncertainty, Swirbul finally had firm footing for his cycling career.

It wasn’t the Strava records that earned Swirbul a job, of course — credit that to his years of experience and racing pedigree. Still, the KOM showed that he had the legs and motivation to put those years of experience to good use.

Those Strava times were confirmation that, despite his many setbacks, Keegan Swirbul still wanted it.

“Normally we’d never recruit based on Strava, but he basically had one foot in the door,” Carney said. “Seeing his motivation, and knowing how a lot of riders didn’t stay motivated, was what did it.”