Progress from process: What it takes to make it to the WorldTour

Photo: Luc Claessen/Getty Images

Will Barta sat by his phone and awaited the familiar buzz of the ringer. It was August 2014, and Barta was expecting a call from famed development coach Axel Merckx. The 18-year-old was anxious and excited.

Barta had dreamed of racing at the top tier of pro cycling since he first began riding a bike as an 11-year-old in Idaho. For years, he had stared at a photo of Fränk Schleck winning atop l’Alpe d’Huez at the 2006 Tour de France, and envisioned himself in such a situation.

Now Barta was at a crucial moment in the progression of young talented riders. He knew that a chance to ride for Merckx’s successful Axeon cycling team could play an important step in his long journey to the WorldTour.

“I was definitely nervous,” Barta says. “I’m kind of a quiet guy, so I wanted to make an impression on him. If Axel offers you a contract, you feel like you’re in the best position you can be in toward making your goal.”

The phone rang. Merckx’s deep, Flemish accent crackled through the receiver. After just a few minutes, he offered Barta a spot on his team.

That moment began perhaps the most pivotal phase of Will Barta’s professional cycling career. Over the next four seasons, Barta raced for Axeon and the U.S. national squad at races across the globe. He made immense sacrifices in his life, and suffered through injuries and setbacks. He scored occasional results, but more often endured disappointment.

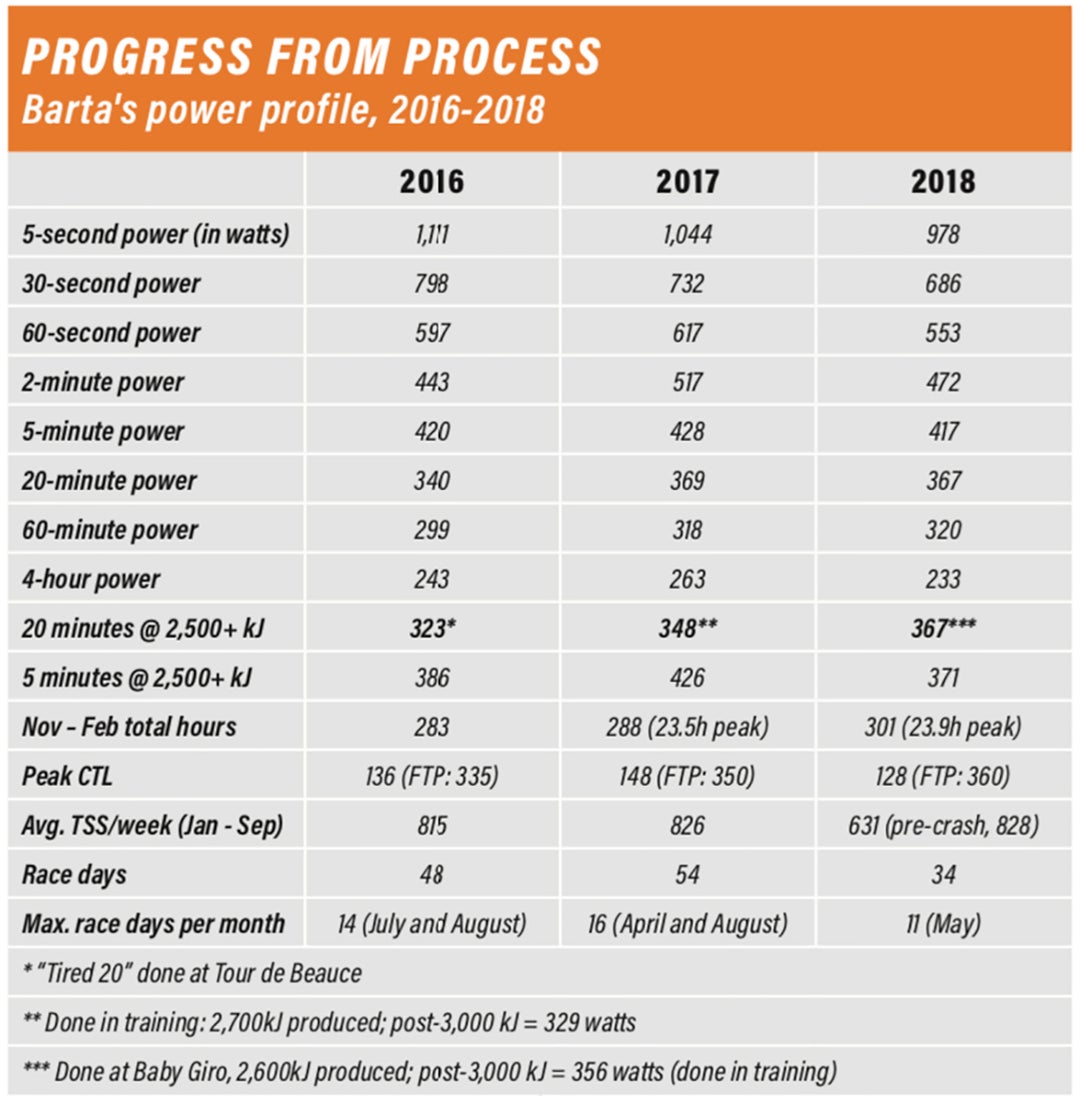

During those four years, Barta’s body grew into a physiological machine capable of handling the training and racing stresses of the WorldTour. And throughout this period, Barta and his coach, Nate Wilson, kept detailed records of his physiological maturation, from a fresh-faced 18-year-old into a young WorldTour pro.

In the middle of 2018 Barta signed a contract with the CCC Team, and in early 2019 he made his WorldTour debut. By March, he was racing one of the most storied events on the WorldTour calendar, Paris-Nice.

“I was super excited to do this race because it has a legendary status and it is always a race the big names do, both from the classics and the GC riders,” Barta says.

Barta’s pathway is one that numerous Americans have followed over the past decade. But no other American rider has chronicled the physiological progression—the workouts, the timeline, the training loads, the power numbers—that takes place as a young cyclist matures into an athlete ready for the rigors of the highest level of the sport.

For this story, Barta and Wilson have shared their data, and given us an inside look at the development process. We’ve broken down Barta’s progression by the four years of his under-23 career. Barta and Wilson detail their process, workouts, successes, and failures as an athlete and coach. By doing so, the pair reveal the process behind the progress, from cycling’s junior ranks to the sport’s highest level.

2015: Going the distance

Barta began racing with the Boise Young Rider Development Squad (BYRDS) when he was 11, and worked with coach Douglas Tobin. Eventually, he became an accomplished junior and regularly contended for the podium at U.S. junior nationals.

Despite that success, Barta was nervous to move up to the under-23 category. He had good reason to be scared. Compared to junior races, U23 races are considerably longer, and U23 riders pedal many more miles throughout a season than juniors.

Barta, who was still coached by Tobin, was most concerned with the race distances. The pair focused on accumulating mileage leading into the 2015 season. Simultaneously, Barta began to train with power.

“I fell a bit into the pitfall of wanting to have the highest average power I could,” Barta says of his first experience with power metrics. “It took me a bit to get going that year.”

Barta’s first races were filled with ups and downs. He began with the Belgian stage race Triptyque des Monts et Chateaux, in which he remembers “holding on for dear life” at the back of the pack in the opening stages. By the last day, however, he found himself as the last man standing in the breakaway. Still, the results were not what he hoped for. Given the success he had in his junior races, Barta had high standards for himself. Yet those around him were telling him he was doing fine, particularly given the big step he had just taken to the U23 level.

A month into the season, Barta finished eighth overall at France’s weeklong Tour de Bretagne. It was an impressive result at his age. Yet he also had hopes of even better things, as the next races had more climbing. At that time, Barta viewed himself as a climber. He ramped up his training. The 18-year-old got his first chance to tackle big European climbs, against a quality field, at the Giro Valle d’Aosta in Italy.

“I think I will still look back on that week as the hardest week on a bike of my life,” Barta remembers.

Unfortunately, he developed a knee injury in the race and it forced him to take some downtime. That meant that he approached one of the biggest races on the U23 calendar, the Tour de l’Avenir, under prepared. Despite that, Barta didn’t implode, and even snagged a top-10 finish on a stage. He deemed the race a mild success.

“When I’d start to ride well, I’d start to get excited, and do too much,” Barta says of his first-year rollercoaster ride. “That’s your standard cyclist’s pitfall.”

At this time, Wilson, who had recently wrapped up a successful racing career as a U23, was observing the training and race data from the U23 national road team in his role as a consultant to USA Cycling.

“I was already pretty familiar with one batch of data from U23 racing—mine,” Wilson says. “I had a bunch of personal data of what these races looked like, and what it took to be successful in some of them.”

Wilson knew it would be a mistake to generalize from his data alone. Other athletes, while they may share similarities, develop at different rates, and present with different strengths and weaknesses at that age.

So Wilson quantified the race performances he was seeing in the European U23 races, including those Barta was doing. Wilson was able to draw a few simple conclusions from the successful races:

- To achieve a top-10 result on a summit finish, a rider must be able to ride, at a minimum, 20 minutes at 5.5-5.8 watts/kg after 3,000 kilojoules (kJ) of work.

- Being able to ride for four hours at 4.0 watts/kg with less than five percent heart-rate drift was a gold standard for general aerobic capacity at the U23 European level.

- Most of the riders graduating to the WorldTour strike a balance: They complete a winter training block to set them up for a successful year, and they come into the season with enough high-intensity training to handle race intensity. That translates to approximately 300 hours of training from November 1 to February 28. “It’s a simple metric, yet one of the most effective I’ve found in this pool,” Wilson says.

- A rider must have the ability to be dynamic under fatigue. “Many of our athletes had the peak power values to be competitive in the top 10, but they lacked the fatigue resistance to access powers over threshold past 2,500 kilojoules of work.” Thus, this became a key area to work: top-end power after 2,500 kJ.

After working with Wilson on the national team, and knowing that he was fresh from participating in many of these same races, Barta hired Wilson to be his coach in 2016.

“It was incredibly difficult for me to switch coaches, because I felt a real personal attachment with Douglas, since he’d been my coach on the BYRDS team for so long,” Barta recalls. “He would ride with us every day, and was and continues to be a large influence in my life, and I feel he is a great coach. But I knew I needed to make the change; I knew I needed a new stimulus.”

2016: Getting intense

In 2015, Barta focused on average power in his training. As Wilson describes it, it didn’t involve much high-intensity anaerobic or neuromuscular work, and really not much VO2 work. It was all about steady power. To progress to the professional level, however, that approach was altogether too simple. Just as importantly, it was relatively taxing training, both physically and mentally.

Stepping up to an even higher level would necessitate that coach and athlete be organized, communicative, and methodical. For someone like Barta who is task-oriented, he thrived when he had a set of daily goals he could tick off one by one.

“I like to train to feel like I’ve accomplished something,” Barta says. “Working with Nate, it was great in that you’d do intervals and he’d come right back to you and say, ‘You did this great, or this is what we need to work on.’ And so you felt every day that you were accomplishing something, even if it didn’t go well, because you were learning from it.”

Barta’s weaknesses at this time were reflected in his performances—he was strong, but struggled with the intensity of some races. Heading into 2016, Wilson made this a key area of focus. Because of the prior data analysis Wilson had done, the pair also had a quantitative roadmap of where they needed to go. They had three years to get there.

“The big picture plan was always to be willing to trade an aggressive preparation that may have led to the best possible following season, for one that would allow for a good following season but also fit into a three-year build,” Wilson says.

One of the first modifications Wilson made to Barta’s approach was to increase intensity.

“I wanted to introduce more ‘polarized efforts,’ by having days where we really pushed to ignore the average power, because we were going to do some very intense work—stuff like sprints, and a lot of tempo work but with anaerobic spikes built in,” Wilson says.

The goal was to improve Barta’s “punch,” his ability to be dynamic at the end of races, to fight for position going into climbs and attack. They began to incorporate workouts that included explosive efforts, as well as strength-work on the bike.

One of Wilson’s go-to workouts he calls Accel<Tempo sets. It includes a series of short, hard accelerations followed immediately by a steady tempo. The efforts accurately replicate fighting for position into the base of a climb. However, doing them at tempo rather than true “race pace” means they are less fatiguing.

Another benefit to these workouts is that they can be incorporated late in rides, in the fourth or fifth hour, to replicate being dynamic under fatigue, as in a race situation.

“This is about as close as you can get to racing without the fatigue. You never really feel like you’re at your limit,” Barta says. “You can also imagine you’re racing when you’re doing them, which puts you into that race situation more often. That gives you motivation while you’re out there.”

Another key workout was slow-frequency repetition (SFR) work, which strengthens the muscles used specifically for cycling. They are often a high-torque, low-cadence hill repeat on a shallow grade done in the big chainring. The big gear taxes the muscles rather than the aerobic system.

“The SFR is incredibly valuable because you’re building an overall strength and you’re also able to work on your technique the whole time,” Barta says. “Both of these workouts are ones you can do, and do well, which is always a nice feeling.”

While seeing improvements in power data was positive, the ultimate goal was improving race performance, not numbers. In Wilson’s experience, U23 riders often saw power data improve in training before they experienced a jump in race results.

“When strength improves, [U23 riders] may have access to some racing tactics that realistically they couldn’t execute before. With that ability, though, usually comes some trial and error of figuring out how to use the strength,” Wilson says.

In Barta’s case, his physical and technical development began to show by mid-season.

In June 2016, Barta had performance breakthroughs at the Tour de Beauce. It was the first time, in Wilson’s experience, that Barta displayed the level he would need to compete in GC-focused European U23 races. His 11th place finish on Mont Megantic and his fourth place in the individual time trial were even better than they appeared to be on paper.

In particular, the ITT caught Wilson’s attention, and served as an incentive for the pair to start investing more time and energy into maximizing time-trial performance. “Will had been telling me for around a year about how he could TT well—but of course it was in his quiet, humble manner and I wasn’t quite fully paying attention,” Wilson says.

The two Beauce results were key contributors to the data portfolio Wilson was continuously compiling on Barta. For example, the Beauce summit finish exemplified one of the metrics Wilson loves to track—an athlete’s so-called “tired 20,” or the peak 20-minute power an athlete can produce after 2,500 kilojoules of work has been completed. The performance at Beauce ended up being Barta’s best “tired 20” of 2016—or 323 watts (~5.5 w/kg at the time).

From Barta’s perspective, however, his results were unremarkable. He often rode in a support role—a role he chose and enjoyed—which contributed to his lack of personal success. He realized that if he wanted to make it to the WorldTour, he had to achieve his own results.

“Being close to that feeling that you can achieve your own results, but not close enough, is the biggest motivator,” Barta says. “Because you feel as though if you put in one percent more, you will get out what you put in with results.”

2017: Making every day count

Before the 2017 season, Barta moved to Nice, France. It was easy for him to focus in that environment, he says. It also felt like he had taken another step in the professionalization of his career.

“I began to feel that if I wanted to be a cyclist, I really needed to make every day count when it came to training,” Barta says.

His training load increased, and just as importantly, he stopped focusing so much on keeping his weight low. He believes this helped him recover better, which in the long term helped him stay fresher and avoid the periods of burnout that had plagued previous seasons.

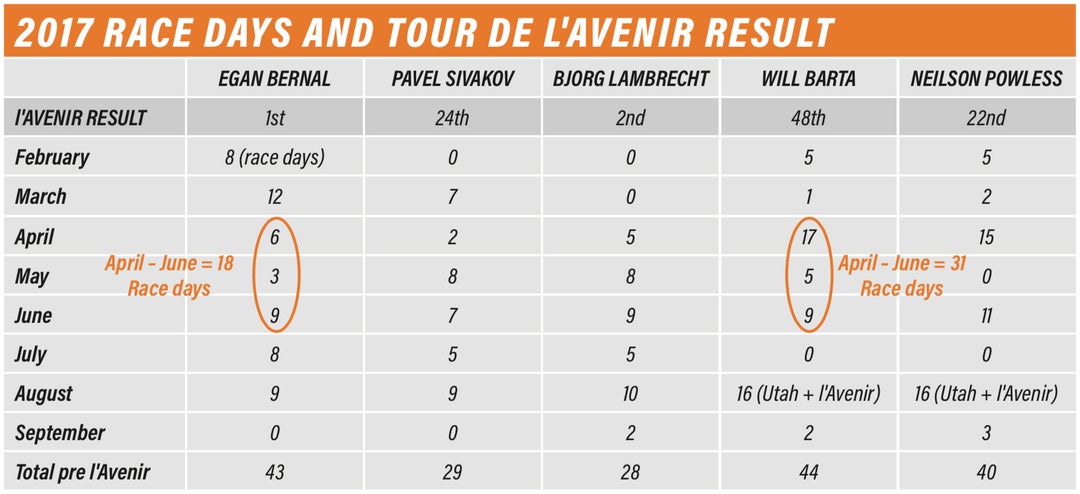

Solid race results followed. From the start of April through the middle of May, he raced four stage races, finishing top 10 on GC in three and 11th in the fourth. Consistency was starting to come. Also in this period, he finished fourth in the U23 Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and fourth in the time trial at the prestigious U23 stage race Triptyque des Monts et Chateaux. It wasn’t long before several larger teams began to express interest in his services, which motivated him even further.

Interestingly, his training leading into 2017 was hardly any different than the training leading into 2016. Overall, the pre-season hours between November and March were nearly the same: 283 hours in 2016 and 288 hours in 2017. Likewise, there was very little change in the composition of Barta’s training. So, little change in volume, little change in the composition, but a change in performance—why?

Wilson credits consistency for the gains. Since Barta’s improvements from 2015 to 2016 were significant though not radical, he decided the best approach was to stay the course; there was no reason to make a substantial change to Barta’s training since there continued to be positive adaptations.

“I see athletes that struggle with the patience to carry out this methodology,” Wilson says. “Everyone wants to be an active dictator of their own future, and sometimes doing the same thing you’ve done before and believing that you are going to improve further feels incredibly naive. However, I really believe a lot of times athletes are doing the right work—but the timeline is one they don’t have the patience for.”

Barta had the patience—and the trust in Wilson—to stick to the plan. “I could talk to Nate about my thoughts,” Barta says. “I think it’s really important that a coach doesn’t just shut you down, and you can have a real discussion about what’s best.”

Unfortunately, the rest of Barta’s season was hampered, first by illness and then by the resulting fatigue of pushing through. As so often is the case, however, it was this moment of adversity that taught him another crucial lesson: It’s important to push yourself in order to find new limits; it is easy to feel that you’re right there and just need one last push; but it is most important to listen to your body and trust the hard work you’ve put in beforehand.

For Wilson, this also proved to be a challenging time. He and Barta were stuck in a reactive mindset, constantly trying to correct course on the fly.

“The reality is, when the goose is already cooked, you can’t get it back to mid-rare, until you start with a fresh goose,” Wilson says.

The second half of that season, Barta was unable to shed the fatigue from the first half of the year. As a coach, Wilson looked for the positive: An analysis of how Barta got off-track would help them avoid the same issue next season.

2018: Building consistency

Before the calendar even ticked over, Wilson and Barta sat down to digest the previous season. Barta took a month off the bike. Then they made a plan. For 2018, Barta was ready to take another step up. He made big goals: U23 Liège-Bastogne-Liège, Baby Giro, Tour de l’Avenir, and the world championships.

When they assessed the takeaways from 2017, it was clear: Barta did so much preparation for the early part of the season, particularly the April races, and then did so many race days that month, that his performances in May and June fell short. Worse still, Barta’s July and August performances were entirely off target.

Something needed to change. The plan for 2018 would include more volume from November to February (~300 hours) to build Barta’s general capacity as a cyclist. Wilson also believed that volume would improve Barta’s robustness, consistency, and the ability to absorb load over the course of the season.

Another important change would be a focus on threshold power. In 2016 and 2017, Barta rarely did any sustained threshold work. This was intentional. Barta was really good in Ardennes style races, and his punch had improved and become less of a weakness.

However, riders Barta could follow on those five to 15-minute climbs were on a level higher than the group of athletes he could follow on 20- to 40-minute climbs. Wilson and Barta both wanted to jump up a group, and to do that they needed to work on the repeatability of Barta’s 20- to 30-minute power, and get comfortable physically and mentally with those longer efforts.

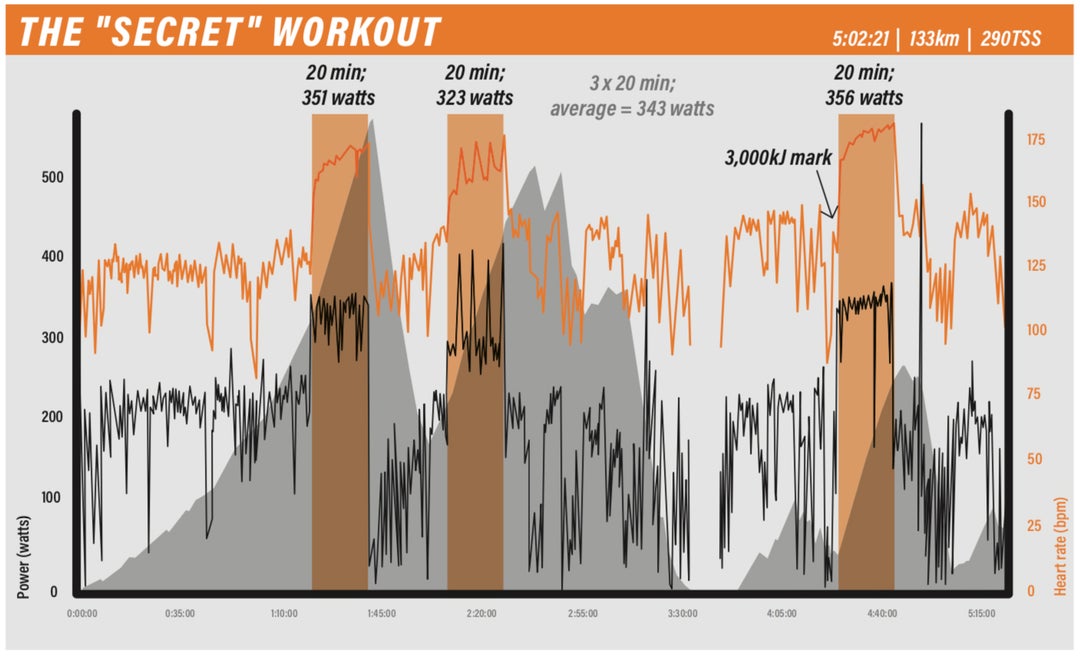

Getting accustomed to longer threshold efforts was relatively straightforward. In fact, Barta’s overall training became simpler, generally. Instead of doing accelerations into a 15-minute tempo pace, Barta did accelerations into a 20-minute tempo. Wilson admits it doesn’t sound like a big difference if done one time. But since they were typically doing three of these sets per session, it adds 15 minutes of hard work in total. When done several times a week, for eight weeks, the total volume was four hours of intense work.

“A large aspect of these 25-30-plus minute climbs we were preparing Will for, it goes past the physiology, and it is the mental ability to be comfortable, being uncomfortable,” Wilson says. “And a lot of that is trained in these repeated long tempo sets—just get robotic, get good at shutting the head off and just tap it out.”

In the past Wilson had placed more emphasis in Barta’s training on changing pace and rhythm on climbs, which helped in technical, attacking races. That meant that when Barta was on a big climb and it came down to 20 rivals, he didn’t have the ability to settle in and grind away.

“I had a little goal for January that I never told Will about, and that was to have him do 3×20-minute intervals on a four-plus hour ride that averaged out to 340 watts for the set, with the final rep coming 2,500-plus kilojoules into the ride,” Wilson says. “If Will executed this, we’d be on our way to improving the consistency and repeatability of these efforts.”

By April, Barta was building well toward his first big objective, Liège. Wilson was focused on managing fatigue, and being careful not to get greedy with how much training Barta did between races. In essence, Wilson made sure Barta wasn’t training reactively.

“In past Aprils, we really focused on training specifically for the style of races we were in,” Wilson says. “The key to a performance improvement in the long climbing races we were now targeting was to remember we were working toward that. So in March, April, May—any time we had a clear enough runway with time to train and not be building destructive fatigue—we’d get straight back into the type of work we had been doing in January. We just kept chipping away at the gap every chance we had.”

However, on the day of the big race things didn’t go well for Barta. He simply didn’t have the legs.

Despite the setback, Barta got several boosts leading into his next main objective, the Baby Giro. His performance at the Tour of California, for example, indicated he was ahead of where Wilson thought he’d be, “Something like that can’t be undervalued,” Wilson says. “I always say consistency is king, but in reality confidence is king. Nothing beats affirmation that what you’re doing is working.”

Barta finished 16th on the punishing climb of Gibraltar Road on the race’s decisive stage. Of his contemporaries, only Brandon McNulty, another powerhouse U23 rider, finished ahead of Barta, while the rest of the top finishers were WorldTour GC riders. It was a breakthrough performance, just in a very under-the-radar way, which is often how Barta showcased his form. The numbers backed up the performance on the road: Barta set a new “tired 20” power record at the time. It was full steam ahead to the Giro.

In his first attempt at a multiple summit-finish stage race, Barta didn’t have a single bad day through the first eight stages. He set another “tired 20” power record, and came in third on the queen stage of the race, which featured a summit finish.

“It was great, four-plus years in the making,” Wilson says.

Unfortunately, Barta never made it to the start line of the final time trial that he had targeted. In the closing five kilometers of the road stage that morning (it was a split stage), he crashed and fractured his femur. He spent the next week in an Italian hospital having surgery and recovering.

The crash left both Barta and Wilson without a result to hang years of hard work on. Still, it was clear the fitness was there. Barta’s ride also affirmed that their process had led to significant progress.

Yet Barta worried that his injury would jeopardize a contract for the following season. Though he knew he wanted to take the step to the highest level, Barta says he was also at peace with the idea that it might not happen.

“I realized that if moving up to the highest level of cycling was not in the cards, I had developed many friendships, been able to see things that I could only dream of, and live a life that I had made mine,” he says.

Barta’s agent, however, had other plans. Gary McQuaid scheduled a meeting with Team BMC. Barta found himself anxiously sitting by the phone once again.

“I think my heart was beating as if I was going into the last kilometer of a race,” Barta says. It wasn’t long before BMC had made an offer contingent on seeing images of Barta’s leg. “Happiness flooded over me and I realized I was just about to the level I had dreamed of.”

While Barta and Wilson did not get to see out their “master plan” for the 2018 season—doing less in April to give way to a breakthrough in August and September—the master goal was making it to the WorldTour. Mission accomplished.

Now 23 and a neo-pro on CCC, Barta sees the 2019 season as only the beginning.

“It’s not enough for me just to make it to the WorldTour,” Barta says. “I know that I need to make new goals for myself, whether that’s chasing wins for myself or helping my teammates to the best of my ability.”

Barta’s place in the sport and on CCC continue to develop. Whether he becomes a rider for the Ardennes classics like he was in his younger years, or if he continues to progress in stage races, or if he serves in a helper role the rest of his career, is too early to say. For the next few years, he’s happy to learn in a helper’s role, challenging himself to develop into a rider who can be there for his teammates in the late stages of a race.

Barta has yet to experience his Fränk Schleck moment. But a kid can still dream.