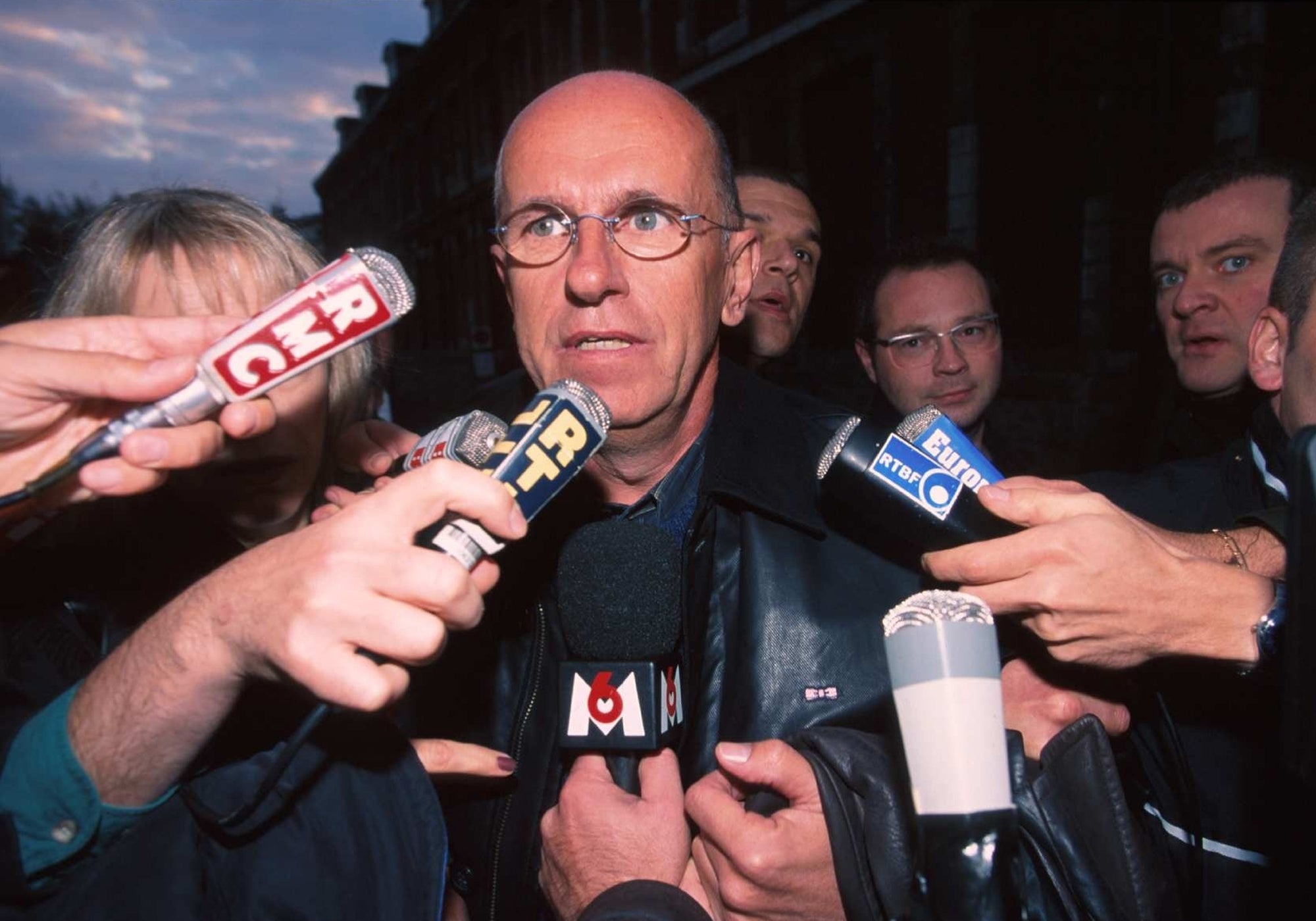

The journalist who broke the Festina scandal

Photo: ©Tim De Waele | Getty Images

Twenty years ago this summer, cycling forever changed. Or at least the perception of cycling did.

In July 1998, what started as a few paragraphs in a report on the French wires about a Festina team car being searched at the Belgian border soon exploded into the biggest doping scandal in cycling history. Before the Tour de France ended that July, scores of riders and teams were ejected, others were arrested, and more simply quit in protest. In what would become the “Festina Affaire,” cycling would never be the same.

We caught up with Francois Thomazeau, the Reuters cycling correspondent who helped break the Festina scandal. Thomazeau wrote the first dispatches about the Festina scandal on the Friday evening before the eve of the Tour’s big depart, starting that year with much fanfare in Dublin, Ireland.

So how did cycling’s biggest doping scandal break? It’s a reminder of how old-school journalism works, based on contacts, context, intense competitiveness, and a bit of luck.

“Our stringer in Lille called me and it was over the weekend, but I quickly put the story on the wire,” Thomazeau recalled. “It was just pure luck. The customs guy who busted Willy Voet was friends with our stringer. From the very first moment, we had the best sources feeding us information.”

It all started innocuously enough. Customs officers stopped Voet at the Belgian-French border near Lille and discovered a loot of doping products in the car, including steroids, EPO, syringes, and other doping paraphernalia. France had recently passed a strong anti-doping law, so Voet was held. Festina officials initially denied knowing him, but the story soon started to unravel. Within a week, Festina’s team manager and doctor were arrested. Contrary to some reports, officials insist they were not tipped off.

“It was a bit of luck on both sides — good and bad — and it changed Tour history,” Thomazeau said. “We didn’t know it would explode into the ‘Festina Affaire.’ It was Friday in London and the big boss was gone. I posted a story based on my feeling that this was big, but I could have been fired. We were ‘alone’ with the story for about two hours before AFP had their own story. We were on the safe side, because we had the guy who was doing the investigation feeding us information.”

Thomazeau is quick to give credit to a Reuters colleague who was based in Lille, the city in northern France where the courts, police, and prosecutors would dig into cycling’s biggest doping scandal. The stringer had deep connections that fed the wires inside scoops on a daily basis.

“I had been a journalist for 12 years, but I had no idea it would be that big,” Thomazeau said. “I had enough instincts and the thing is, it looked odd. I could have just written a short story, but I sent it out as a breaking story. I felt it was important enough to be sent as an urgent story.”

The story seemed to stall over the weekend because in those days, everyone checked out in France. Voet was being held in a French jail cell, but all the judges and prosecutors ultimately involved in the case didn’t begin to seriously dig until the following week. And France had just won soccer’s World Cup. By the time the Tour de France left Dublin and arrived in France on the Tuesday, the story was starting to heat up.

“We broke the story with just a few paragraphs and then slowly started to fill out the details,” Thomazeau said. “By the time we got to France, the story started to blow up.”

As the story developed, Reuters leaned on its sources in Lille in the courts and police to get out information. The game was played both ways, as officials used the media to squeeze teams and Tour officials.

“It was the World Cup final and France just beat Brazil. No one cared about a doping story,” he said. “It started to gain steam when we realized who Willy Voet is. He wasn’t just anyone, he was the top soigneur for the team. We got to Cholet [stage 4] and [team manager Bruno] Roussel was arrested. Then it went wild.”

Thomazeau, who’s covered 26 complete Tours, said the technology and media landscape at the time hampered but also helped the story. Cell phones and the internet were still in their infancy and Twitter had yet to be invented. The journalistic standards of the day were much higher than in today’s 24-7, Twitter-fueled immediacy.

“We had a cell phone, but we didn’t use them much in those days. We still used a fixed line to transmit stories,” he said. “The standards of the day were much higher then. Today people just copy other reports or take something off social media. In those days, we really needed the source and a source that we knew and trusted.”

Thomazeau, who is a regular on The Cycling Podcast, shared an interesting anecdote about how the news moved decades ago. One day before one Tour started, legendary Reuters cycling correspondent Mike Price had stopped to fill up his gas tank when he spotted Stephen Roche dressed in street clothes. Price asked what was up and Roche told him he was out of the Tour.

“Roche said, ‘I hurt my knee, my Tour is over.’ We called it in from the gas station and we owned the story for hours,” he said. “These days, we’re lucky to have a story for five minutes. Now it’s a vicious circle. Today if you get a nice story everyone just copies it instantly.”

That year’s Tour dissolved into chaos. By 1999, the “Tour of Renewal” began with the arrival of Lance Armstrong and another decade of doping scandals were still to come. It’s hard to say how much cycling has changed since those days, but Thomazeau is sure that the foundation of good journalism remains unchanged.

“Good journalism is like good cuisine,” he concluded. “If you want to cook pasta, it takes seven minutes, you cannot do it faster. Good journalism is not a question of the old school or a new way; it is the only way. There is one way to do it. If you want it fast and easy, you get McDonald’s.”