The Outer Line: The UCI Points System: original Intent, current effects and future recommendations

Quintana has found a new home at the French team. (Photo: Michael Steele/Getty Images)

It’s easier to complain about the UCI points system than it is to eliminate its subjective inequities and unintended consequences. Therefore, we recommend that any future promotion/relegation process only utilize WorldTour events toward the ranking.

The almost universally derided UCI points system has been increasingly scrutinized this year – as it has become one of the prime determinants in the battle for the upcoming three-year WorldTour licenses. The complicated promotion/relegation battle has often overshadowed the actual racing and has become one of the most closely scrutinized contests in recent years.

Also read: The Outer Line: Is it time to shake up the pro cycling calendar?

Observers question the fairness, accuracy, and the unexpected or contradictory incentives the points system has created. Below, we review the intent and current effects of the system, and offer recommendations for how it should be used in the future.

The points system is one of the UCI’s primary management tools to both monitor and guide professional cycling. First, it is an attempt – however subjective or flawed – to quantify competitive performances of professional cyclists across a wide range of different types of events into a ranking model. It is a more subjective competitive ranking system than used in most other sports due to cycling’s nuanced characteristics and metrics; points earned by individual riders are even aggregated to also rank teams and nations.

Second, the UCI employs the points system to subjectively determine the relative importance of different events. In the case of longstanding races, the point system attempts to reflect the historical significance of the event. In other cases, the system may be proactively utilized by the UCI to establish, and therefore promote, the relative importance of newer or smaller events. The UCI can effectively determine the hierarchical importance of new lower-level races by allocating more or less points, in turn influencing the rider selection of teams at those races. Hence, the awarding of points in this sense becomes a tool to manage growth or diversification; and it is inherently open to political pressure, as new or regional organizers try to develop a higher profile for their events.

Also read: The Outer Line: The ‘Relegation Watch’ and what it means for WorldTour licenses

There will always be debate about the proper way to balance and award cycling’s “points” – based on both the perceived prestige or challenge of individual events, and the relative performance of the different individual athletes. Let’s dig into both of these objectives of the system to understand where the system works and where it may falter.

Points as a competitive performance measure: stated bluntly, there is no objectively “right” or single way to measure performance in cycling. No system that blends subjective and objective rankings will ever be perfect. Even though many fans perceive the ProCyclingStats (PCS) ranking system to be more detailed and accurate than the UCI’s, it is also subjective. For example, there will always be debate about how to rank the performance of a beefy sprinter on a flat stage versus a skinny climber on a mountaintop finish. While there is a tendency to try and stratify such metrics in greater detail, it’s also important that the system be practical – easy to use, track and report. Today’s system – often derided as being overly simplistic by critics – is so difficult to maintain that the UCI itself makes mistakes in tallying the results; indeed, outside parties sometimes double-check and correct the stats.

The UCI system’s unbalanced and inaccurate weighting is best illustrated by the WorldTour one day races, in which the top sixty finishers all receive points. On the other hand, in the individual stages of a grand tour – many of which are much more hotly contested and far more widely watched – only the top five finishers get any points at all. A top sprinter edged out for fifth on a grand tour stage – perhaps only inches behind the winner – will receive just five points. Meanwhile riders who come in as low as fiftieth in far less popular and visible races like Eschborn-Frankfurt or RideLondon-Surrey also get five points. These kinds of apparent inequities are widespread in the current system.

Points as a determinant of the relative importance of races: a primary UCI objective is to build and promote new races in new parts of the world and to diversify the sport. The current system allows the UCI to arbitrarily award disproportionately high points to relatively new or under-noticed events. This practice imbues more importance to a given event, thus influencing the quality of riders that teams send to the race and, in effect, increasing the prestige.

This practice potentially opens doors to political influence and commercial interference, as indicated by the following few examples. The winner of the wildly popular Strade Bianche race gets just 300 points – the same as the Gree Tour of Quangxi, a race which many diehard cycling fans have never heard of. Canada’s lower-profile autumn grand prix races offer 500 points per victory; in 2019, Belgian star Greg van Avermaet flew in, won Montreal and placed third in Quebec, to haul in 825 points. Compare this to the Giro d’Italia – cycling’s second biggest grand tour, incorporating 21 grinding stages over some of the world’s steepest mountain passes. Earlier that year the winner, Richard Carapaz, picked up only 25 more points (850) for his three-week effort than van Avermaet did on two weekend afternoons. More recently, Simon Yates picked up more points for winning Prueba Villafranca Ordiziako Klasika – a tiny Spanish race – than Jasper Philipsen earned for winning the glamorous and iconic Tour de France finale on the Champs d’Elysees.

How some of these preposterous inequities made their way into the system in the first place boggle the mind, and many of them could easily be corrected. But another aspect to consider here is that the UCI can’t be willy-nilly changing its system every time a problem pops up – because that makes it impossible to compare performance trends over time. It already adjusted the system a few years ago, making it impossible to compare points performance numbers over the longer term.

While the inconsistencies and inequities of the UCI points system have been endlessly debated, they have historically not constituted a major problem for the sport. However, this year – for the first time – the UCI points system has been used for a much more direct and economically critical purpose. It has become a major determinant in deciding who will and who will not receive an invitation to receive a UCI WorldTour license for the 2023-2025 time period – the infamous promotion/relegation (P/R) battle which has been gradually heating up all year, and which now attracts a huge amount of media attention on almost a daily basis.

All of the WorldTour teams, plus a handful of the best second-tier ProTeams, are furiously competing to finish 2022 among the top 18 in terms of points earned over the past three years. Making the cut may well be a matter of life and death for many of those in the relegation “death zone.” Teams above the cut will be able to achieve greater economic stability and more opportunities to attract more sponsor dollars. At the moment, there is a strong likelihood that two existing WorldTour teams will be downgraded to the ProTeam level for the years 2023-2025.

Whereas previously UCI points were “nice to have” and good for bragging rights, they are now critical to economic survival. Not surprisingly, teams have begun to develop a laser focus on acquiring points by any means possible. A mad scramble has developed, with some teams employing apparently counter-productive approaches and strategies to try to maximize their totals. In this process, some hitherto unrecognized shortcomings and counter-productive incentives of the UCI points system have been revealed. Consider the following:

(1) Teams may be incentivized to not win a race, but instead snipe multiple top positions to maximize points. The current UCI system makes it advantageous to have several riders finish high in the standings, rather than working together to get one rider the win. Arkea-Samsic opted to take 3rd, 4th and 7th places (scoring 285 points) at Kuurne-Brussels-Kuurne this year, rather than working for a leader who might have scored 200 points for the victory.

(2) Arkea also declined its ProTeam invitation to the Giro d’Italia and sent its riders to several smaller races instead, correctly assuming they would be unlikely to contend for stage victories or the overall. Because of a UCI policy that favors the top two ProTeams Arkea was allowed to skip a marquee event, and in the process piled up more points than most of the WorldTour teams were able to garner in May.

(3) Similarly, several teams have been sending their best riders to second-tier races, where they can feast on weaker competition and gobble up points – as Israel-Pro Tech did at the Mercan’ Tour Classic Alpes-Maritimes. This practice dilutes the fields at other more established venues.

The current points system rationalizes and rewards anticompetitive behavior such that we may soon witness teams working with their rivals to block others from leap-frogging the WorldTour rankings.

For example, Israel-Premier Tech may realize it won’t be able to make the 2020-2022 top 18 rankings and could instead work for Lotto-Soudal in every race to collude and overtake the EF team. (Due to the complex structure involving both the three-year and the one-year rankings, if Lotto earned the final promotion spot instead of EF, IPT would be guaranteed invites to all 2023 WorldTour races, instead of simply the one-day WorldTour races.)

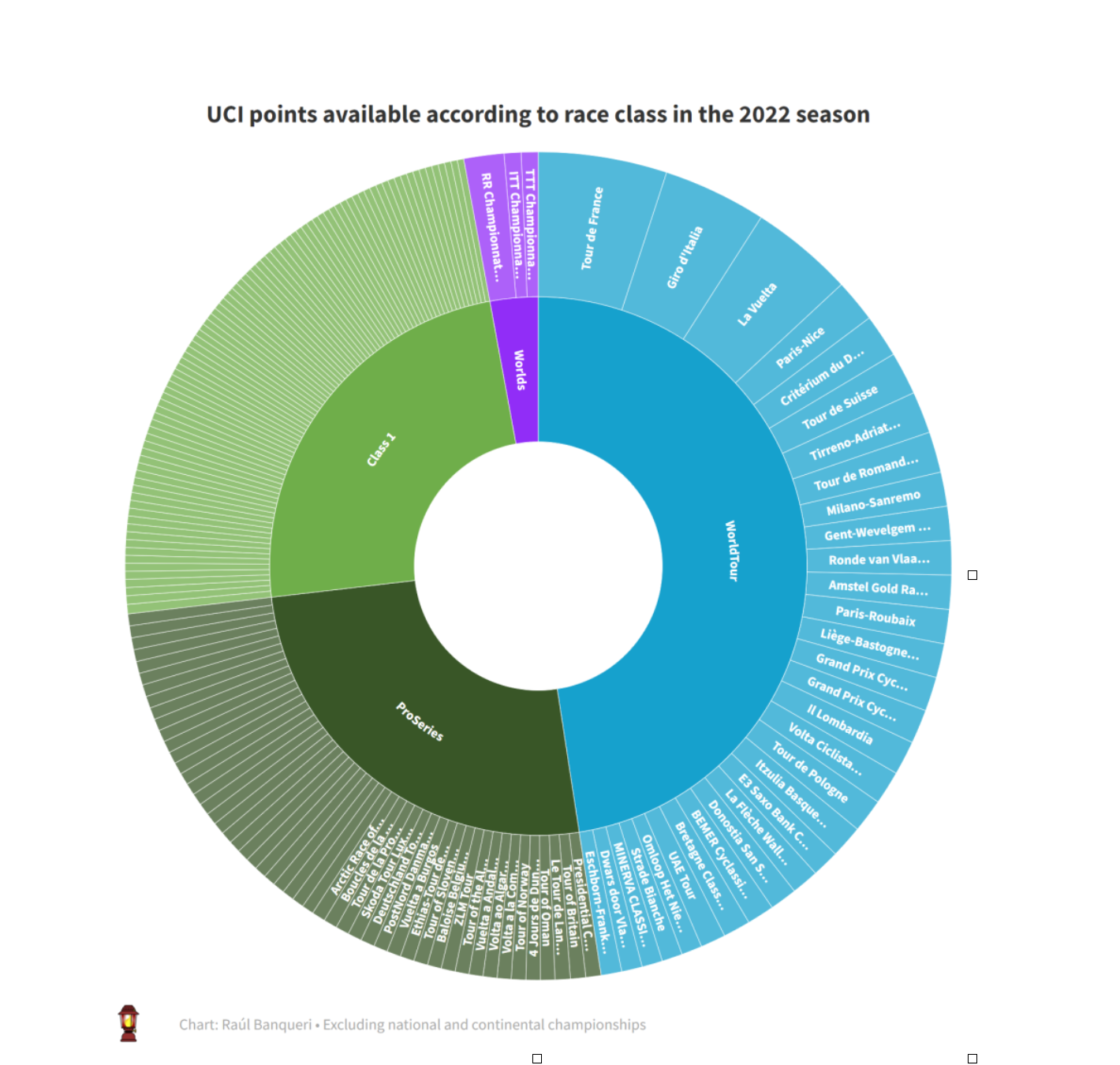

So, where does this leave us? There are incremental and easy ways to improve the system, summarized in all its glory in the Chart, by the undisputed master of the UCI Points System – Raul Banqueri of the Lanterne Rouge website. The blue represents the WorldTour events, purple the World Championships, and green all the rest of the ProSeries and lower level UCI events. As shown, WT events count towards slightly less than half of the total WT points available in a season – meaning that there are lots of ways for WT teams to garner points beyond competing in WT events.

First and most simply, GT stages should award points to more than the top five riders, and other WT events probably should not award riders all the way down to 60th place (which in some cases allows half the peloton to earn points). The relative prestige of individual events should also be revisited and updated to their positions in the calendar.

To further improve the situation, we recommend clearly defined participation expectations for teams in participating in any promotion/relegation processes in the future. As a starting point, we would simply suggest that only WT events “count” in terms of amassing points for the P/R battle. All teams aspiring to keep or earn a WT license would be expected to race the same events, with no more cherry-picking or skipping invitations to trawl for points in the undercards. At the very least, there should be a cap on the number of races from which teams can amass points.

There is also a need for the UCI to rethink the privileged status offered to the top two ProTeams. Although the original intent was to creative a strong incentive and opportunity for top ProTeams to move up, this “loophole” is now being exploited to the detriment of the sport. The current system allows teams like Arkea to simply sit out of difficult events (e.g., the Giro) while rolling up easy points in smaller races where the competition is much weaker. It also allows them to come into later events (e.g., the Tour) with a much fresher team – meaning teams aren’t competing on a level playing field. The UCI should rethink the unique preference that this rule currently gives to the top two ProTeams, which is essentially, the right – but not the requirement – to attend all WT races. Since all WT teams have to attend WT races, it could be argued – from both a competitive and financial/sponsorship perspective – that the optimal position in pro cycling is to be one of those top two ProTeams.

As is often true, it is easier to complain about the current system than it is to offer productive and solid suggestions for how to improve it. While there are some obvious ways that the system could be tweaked to remove obvious inequities or unintended incentives, no system will ever be perfect. However, when employed to make critically important economic decisions, a much simpler and more restricted system for awarding points would simultaneously make the promotion/relegation competition fairer for the participants while maintaining a more competitive racing environment.