The power meter debate rages on

Photo: Chris Graythen/Getty Images (File).

A growing chorus is suggesting that pro cycling should ban power meters to jolt life into a moribund peloton.

Movistar’s Nairo Quintana, ex-pro Alberto Contador, power-brokers such as UCI president David Lappartient and Tour de France director Christian Prudhomme — they all say power meters are sucking the life out of racing. Not everyone agrees. Mitchelton-Scott sport director Matt White said power meters are not the reason for cycling’s perceived malaise.

A yellow jersey monopoly

The logic goes that if riders are forced to race on instinct and guile rather than lean on the technological crutch of data on a computer screen, racing would bound back to its unfettered and unpredictable roots.

Many fear that the sport, despite having gone a long way to spruce up its once bad-boy doping image, is now losing eyeballs because races seem too controlled. The restrained pace of modern racing, especially at the Tour de France, results in time gaps measured in seconds, not minutes. That’s why some suggest the northern classics — where brawn, not calculations, matter — are the last bastion of true racing.

Every conversation about the Tour starts and ends with Team Sky and the dominance of Chris Froome. Critics draw a straight line between Sky’s ever-dominant style directly and the power meter. Take away the power meters, the logic goes, and you take away Sky’s primary tool of monopolizing the yellow jersey and, by extension, revive cycling.

Some fans are yearning for the glory days of cycling’s past. Peruse any account of grand tours from Coppi to LeMond and readers are astonished to learn that riders could lose eight minutes in a mountain stage, only to bounce back and regain all that and more the very next day.

These days, racing is so highly calibrated and controlled that it’s become a race of attrition. It’s less about attacks off the front and more about who has the engine to stay on the wheel and not get dropped. Of course, there are exceptions — look no further than Froome’s dramatic Giro coup over the Colle delle Finestre in May — but no one denies cycling’s dynamics have changed.

Although his team is usually racing against Sky, White, speaking to VeloNews in a telephone interview, isn’t buying it.

“I think it’s ridiculous,” White said of the argument to ban power meters. “I think it’s some people grasping at straws. Nothing is going to change if they ban power meters. Nothing.”

White is a contrarian voice to a steady drumbeat among racers and observers who say power meters are making races boring.

“Power meters isn’t what’s making the racing seem predictable,” White added. “There are a lot of reasons, but power meters isn’t one of them.”

A revolution in control

Power meters have revolutionized training and racing in the peloton since they were introduced nearly two decades ago.

Like a heart-rate monitor, a power meter provides real-time data. But there is a major difference — while heart rate data fluctuates, depending on a rider’s fatigue or other factors, the wattage data measured by a power meter is always true to the cyclist’s output. When you look at a number on a power meter screen, it is simple to translate that into a rider’s performance on the road, especially in an individual effort.

This allows riders and teams to calibrate training in ways that were unimaginable with previous technology such as heart-rate monitors. Coupled with advanced computer modeling, power meters allow riders and coaches to fine-tune training and preparation not just to hit a peak in July, but to target individual climbs on stages and even down to the granular level like a specific ramp of a climb.

(Learn why training by heart rate still matters.)

Many believe power meters have changed the nature of racing in such a radical way that they leave the sport devoid not only of the drama and the unexpected swings of fortune that once made it so appealing but they have transformed racers into little more than drones racing off a spreadsheet.

The idea of banning power meters during competition is gaining traction just as Team Sky continues to tighten its grip on the yellow jersey. The UK juggernaut won four grand tours in a row from 2017-2018, and it has won six of the past seven editions of the Tour de France. With Colombian sensation Egan Bernal waiting in the wings on an unprecedented five-year contract, it appears Sky’s stranglehold on the Tour could stretch well into the next decade.

World champion Alejandro Valverde (Movistar) is also on board with a potential power meter ban: “Team Sky is expert when it comes to racing with power and speed. It’s a big factor for them. You’d notice it more in the moment of controlling the race. They’re there [at the front] because they have the fitness, but if you take [the power meters] away, maybe the outcome would be different. It’s worth trying out.”

The idea of banning power meters has been knocking around the past few years, but it seems to be gaining steam as more voices join in.

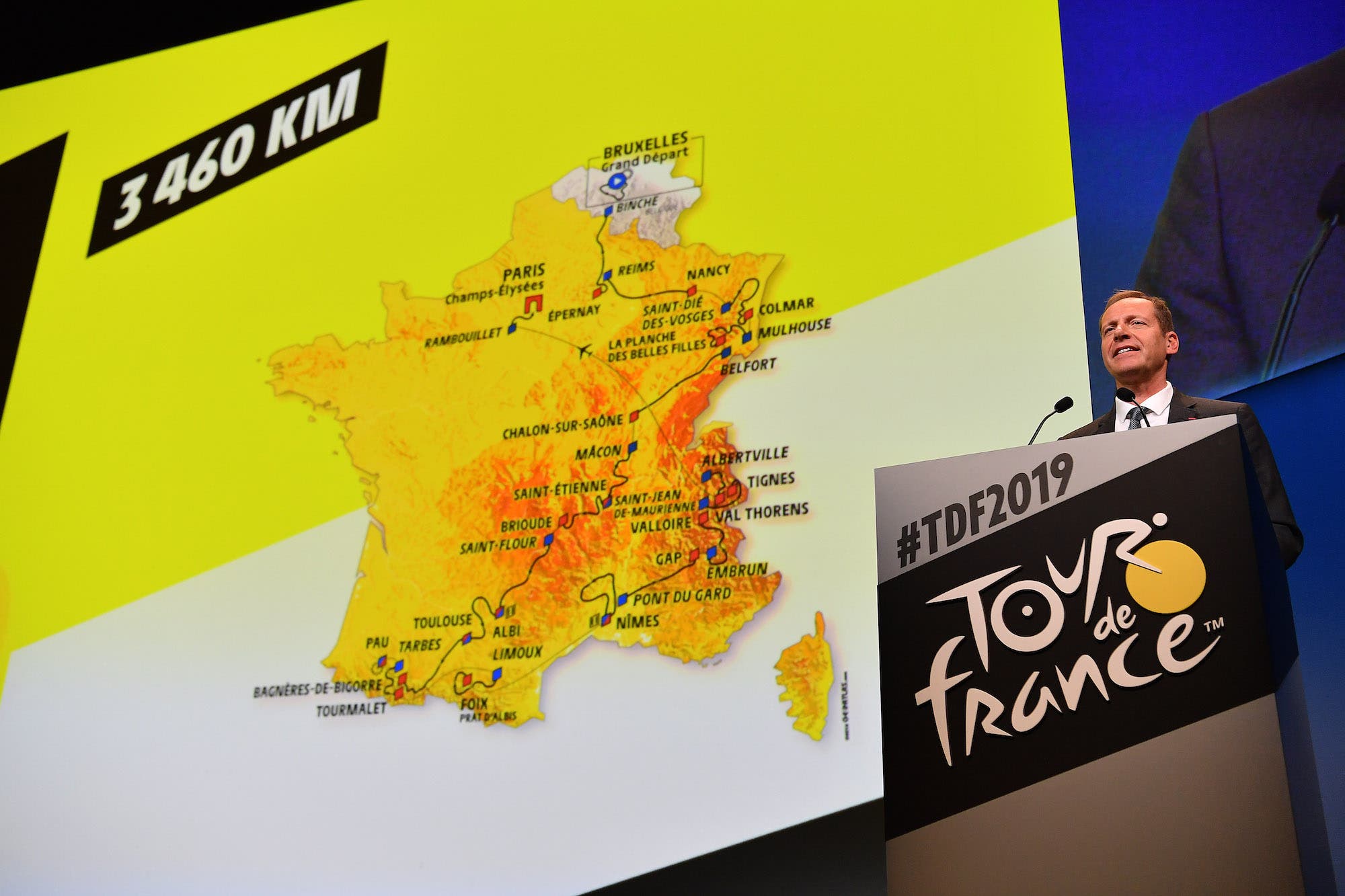

Tour boss Prudhomme put his weight behind the idea during the rollout of the 2019 Tour presentation. “We reassert our desire to see the end of power meters in races, which annihilate the glorious uncertainty of sport,” he said.

Power meter proponents don’t want to ‘step backward’

Ban-backers say it’s obvious riders pace off the readings. Everyone knows their threshold power, so when a brave rider dares attack on a steep climb with 8km to go, rivals immediately check their power numbers and realize that no one can hold that power for more than a short burst. Workers set a high tempo and reel in the offending attacker, who often then runs the risk of getting dropped in the final thrashings toward the line when the favorites make their surges.

Take away the power meters and voila! Racing would again become interesting.

White isn’t so convinced.

“Anyone who attacks like that these days is crazy,” he said. “It’s just not as aggressive as it used to be … but the reason isn’t because of power meters in the race.”

White eschews the idea that power meters have that much impact. Come race day, you either have the legs or you don’t. That hasn’t changed since days of Lucien Petit-Breton.

“Of course riders use their power meters in a race. But if they were taken away, people would adapt quickly,” White said. “It’s like going back in time. It wouldn’t change a thing in terms of who wins the race.”

White isn’t the only who thinks banning power meters would be a “step backward.” Managers such as Jonathan Vaughters (EF Education First-Drapac) and others believe cycling should embrace technology as a way to engage the fans. Some dream of a fully integrated, real-time data-driven dashboard, much like viewers see in Formula 1 so that fans can get inside the peloton.

There’s already some adaptation of that model. Velon, a cycling group backed by many of the peloton’s top teams, has provided revealing insight into what really goes into manhandling an hors-categorie climb at race speed. Yet some teams, especially Sky, are loathe to give away their power numbers. Team Sky guards Froome’s power data as closely as the Coca-Cola recipe.

Instead, White has a laundry list of reasons why the peloton doesn’t see 10-minute swings in GC anymore. First, the level across the peloton is higher than ever before, thanks in part to better training. Riders and teams are more professional, and there isn’t as much of a difference between the top winners and the workers. Science, diet, coaching, equipment, and recovery are all light years ahead of where they were even just a decade ago. Racing is more intense, meaning there are no more easy days in the saddle when the peloton could recover between hard mountain stages. Race course design has evolved to make every stage count, so riders are less inclined to take big gambles. And, if you dare to believe it, the peloton is dramatically cleaner than it was during the EPO era when PEDs and blood transfusions were fueling many of the big-ring heroics.

“The style of racing has changed, and I think it’s changed for the good,” White said. “Everyone compares it to the past … but we need to look forward. It’s still exciting, but just in a different way.”

Money, not power meters, wins the day

Changing rules doesn’t always deliver the intended results. In 2018, the UCI reduced grand tour squads from nine to eight. What happened? Team Sky still won the Tour — and the Giro d’Italia — yet many teams reduced their rosters. Sky still ended up on top, but a handful of riders and staffers were out on the street.

White says people have it all wrong. It’s not power meters that are spoiling pro racing — it’s money.

“Taking away the power meters is not going to restrict Sky. If you really want to restrict Sky, the best way would be to implement some sort of salary cap,” he said. “If you’re serious about leveling the playing field, some sort of salary cap would be the best way.”

The notion of creating salary caps and budget limits is also making the rounds. Many agree with White that budget disparities between the peloton’s haves and the have-nots are equally grave to cycling’s unpredictability and spontaneity.

How to create an egalitarian peloton is a very tricky question. Impose an NFL-style salary cap only to have riders get paid under the table? Or trim budgets in a sport that desperately needs more money, not less? And any budget restrictions would be nearly impossible to regulate in a sport where teams are based all over the world across different currencies with diverse tax laws.

White attributes Sky’s dominance to its seemingly unlimited checkbook than to the use of power meters.

“Every team would love to have their resources they can bring to the races. They have so much depth,” he said. “If you restricted the budget, then you could restrict their depth.”

Riders like Wout Poels and Sergio Henao (heading to UAE-Emirates in 2019) might not be winning the Tour on other teams, but they have the motors to do their job pacing Geraint Thomas or Froome better than anyone in the peloton.

Sky is reportedly paying elite domestiques more than $1 million annually — nearly as much as top salaries for GC captains on other teams — and only a handful even make the selective Tour de France squad. Some teams are racing on a budget less than a third of Sky’s. Would Froome have won so many Tours on a team with a smaller budget? Would Tom Dumoulin have already won the Tour if Sunweb could triple its budget? Those questions are impossible to answer, but obviously, Sky can buy the top domestiques to control the peloton while most other teams cannot.

“You go to a team hotel during the Tour and they have an extra table of staff that you don’t even know what they do or who they are,” White said. “The budget is the game-changer. That has the ability to stack their roster with riders and nobody else can do that.”

White, however, insists Sky isn’t unbeatable. After trying for years, Mitchelton-Scott nearly won the Giro d’Italia in May facing off against Froome and finally won its first grand tour with Simon Yates at the Vuelta a España.

“I think most people who complain about power meters are just sour grapes,” White concluded. “They can’t beat [Sky] at Paris-Nice, let alone the Tour. Try beating them at a one-week race before aiming for the Tour.”