VN Archives: Beth Heiden wins worlds

The last half century has produced countless amazing moments in pro cycling, and VeloNews has been there for almost all of them. This year we celebrate our 48th birthday. With 48 years worth of archives, we want to present some of the more memorable VeloNews covers, feature stories, and interviews from our past. Our hope is these curated snippets will help motivate you to pursue your passion for the sport you love. The following article originally ran in the September 26, 1980 edition of VeloNews.

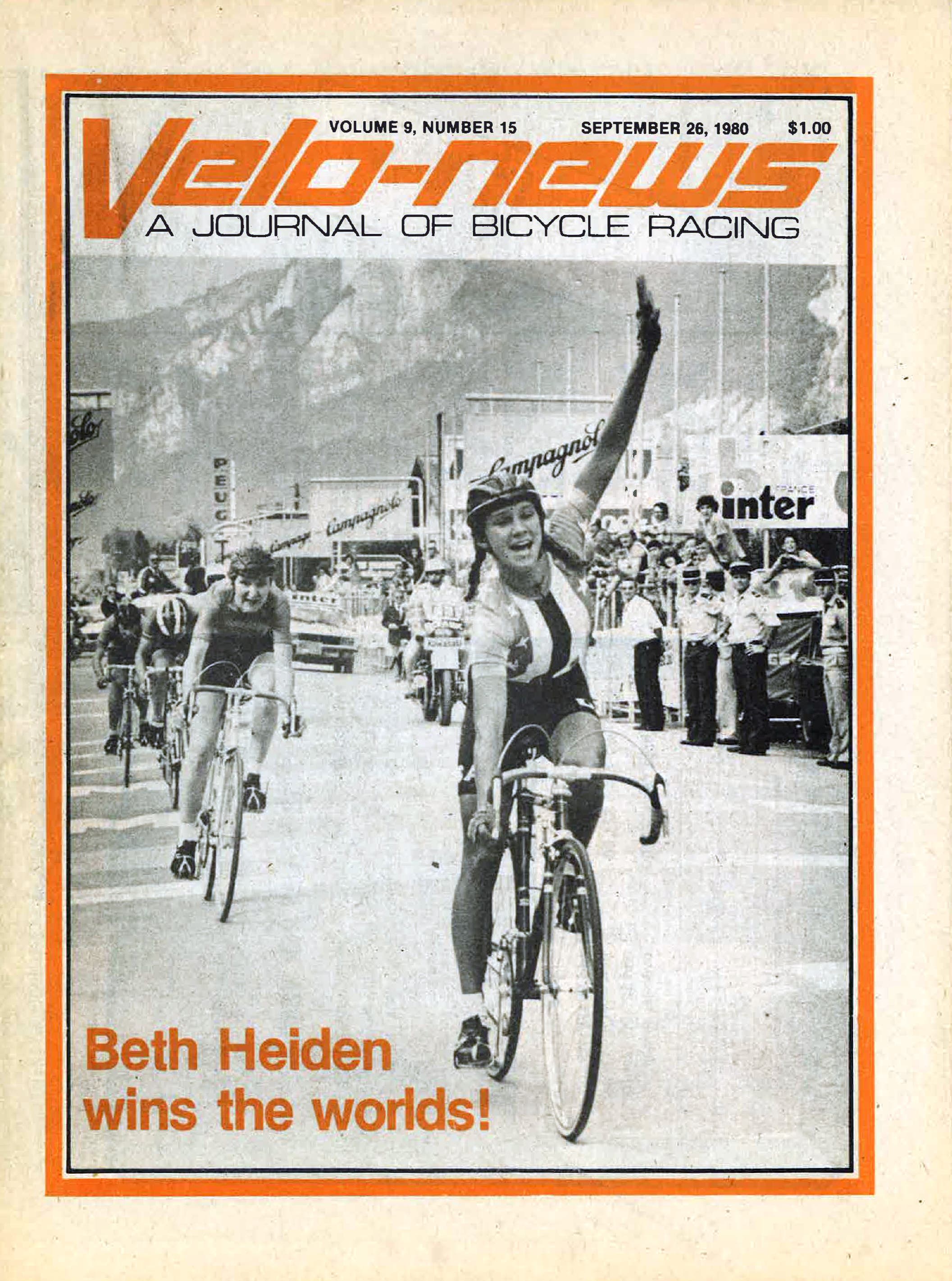

Champion of the world! Miss American Express hammered across the line here in Sallanches, France, Aug. 30 to give the U.S. its second current world champion. As she wept for joy she told me: “It’s great. It’s wonderful. I can hardly believe it.”

But Beth Heiden was due back at reality all too soon. The pert 20-year-old, who stood on the rostrum in her rainbow jersey as the anthem played, was to be back at the University of Wisconsin just two days later. On the way she would appear on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” and announce that, next to studies, cycling and not speedskating is to be her future big interest.

Let’s hope so! Her’s was a truly classic championship win and the crowd loved it. “There couldn’t have been a more popular winner,” said Miji Reoch, Heiden’s most experienced teammate. “Going up that last hill the crowd was reaching out and pushing me because they’d heard Beth had won. They were as delighted as we were. I hardly had to pedal all the way up.

“It was Reoch who played the background role to Heiden’s success. The young woman in pigtails just never thought she could win, according to Miji. “I knew right from the start of the year that Beth could do it,” she said. “She’s been riding brilliantly all season and I just knew she could win the world championship. I think she just lacks confidence in herself.” Heiden was the first to acknowledge that support.

Within moments of escaping from the finish line crush, she had words of thanks for two people — her father, Jack, and Reoch.

It was a tough guys race and one for which the Americans were ideally suited. The circuit clung to the edge of the Alps within the shadow of mighty Mont Blanc, Europe’s highest mountain.

The game plan for coach Karen Roy and her riders was for the rest of the team to back Heiden and Heidi Hopkins to the hilt. On the first of four times through the toughest climb — veteran professional Roger De Vlaeminck told me the very thought of it gave him a stomach ache — the Americans were spread across the front of the bunch like a seawall. “There was no real attack,” said Heiden, drinking French mineral water in the pits, “just a case of the strongest getting clear. We kept on riding and the others dropped off one by one.”

Just 20 minutes into the 33.5-mile race the front group numbered only seven, with Heiden and Hopkins taking along tall Swede Tuulikki Jahre, Briton Amanda Jones, the Italian Francesca Gali and two others. The race had ended so far as the rest were concerned. On hills so hard that it was basically a race of attrition, the tiny group bobbed and weaved toward the finish. By the end of the first lap the gap was 15 seconds on Holland’s Hennie Top and the ’78 champion, Seate Habetz of West Germany.

The bunch was already in bits and it became obvious that only an accident could possibly change things. For the Americans in the pit area, it was all looking too good to be true. Something had to go wrong — and it did.

Brave Heidi Hopkins slid painfully off the back, something she was to do three times in all. But on this occasion and the next she caught up again. The third time she didn’t. The chases just took too much out of her.

Hennie Top was down to 1:50 with one lap to go, trying yet again to salvage something of the reputation the Dutch have built over the years. She caught Sweden’s Pia Prim, who had slipped off the break, and the two of them struggled through the start/finish area ahead of a whole succession of chasers, including Canada’s Karen Strong at three minutes.

By now the rest of the Americans were well out of the running, with Betsy Davis and Rebecca Daughton nearly seven minutes in arrears. Daughton, an unknown 22-year-old from California, had looked positively nervous on the line — she confessed to being both that and a novice at international racing. “Beth and I came over a couple of days before the rest of the team just to rest up,” she said. “I take my advice from Beth. I don’t know about jet lag and stuff like that and I just do what she does.”

When the break, down now to four riders, came into the finishing straight through the center of downtown Sallanches for the final time, it was Heiden and the Italian Galli who shared the lead. The speed dropped as first Galli and then Heiden took the quartet across the road, each trying to persuade the others to jump. It’s difficult to say exactly who made the first move — probably it was a joint reaction sparked by Tuulikki Jahre, the Finnish-born girl who moved to Gothenburg, Sweden, when she was 10.

Whatever caused it, the reaction was immediate. Heiden slammed her way up the right-hand side and the others didn’t stand a chance. She whipped over the Campagnolo and Oceanic signs painted on the road and flung her arm in the air with perfect composure.

Jahre was second and given the same time, but by appearances she was a good 10 yards down. Amanda Jones was third to end a long medal drought for Britain. Galli, who had had a hard time on some of the climbs, was fourth and one reason for Jahre’s downfall. Tuulikki said afterwards: “I am disgusted. I came to this race only to win and the gold medal is all that interests me. I thought Galli was going to win and I was only looking out for her. Then I saw the American go and it was too late. There was nothing I could do to catch her.”

Jahre has staked a great deal on world-level cycling. Her mother’s insistence that she stop racing and study to be a doctor led Tuulikki to move out, and now they have very little to do with each other. She does work in a hospital, but as a high-level nurse.

Heiden told the throng of reporters: “I did not attack on the last lap because I wasn’t sure how good the others riders were. I was watching Galli, especially when she attacked on the last hill. This was a good circuit” — she burst out laughing — “well, naturally l’d think that, but it was a good circuit because it had something to test the climbers but enough descending and flat to even it out. It certainly tested everyone with all that twisting and turning.

“For me, it is hard to compare my bronze medal at Lake Placid with the gold medal today. In speedskating the important thing for me was to record my best-ever time. In cycling many things happen, you have to think a lot, there are other riders there and it is very exciting.”

Heiden said the Coors Classic was important preparation for her ride and she had no time for those who said Sallanches was too hard a circuit for women.

“I think it was a great circuit,” she repeated.