VN Archives: Obree smashes Boardman's hour record in 1994

The last half century has produced countless amazing moments in pro cycling, and VeloNews has been there for almost all of them. This year we celebrate our 48th birthday. With 48 years worth of archives, we want to present some of the more memorable VeloNews covers, feature stories, and interviews from our past. Our hope is these curated snippets will help motivate you to pursue your passion for the sport you love.

Last week the cycling world turned its collective gaze on Victor Campenaerts, who set a new UCI Hour Record (55.089km) at the Velodromo Bicentenario in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Campenaerts’s record ride penned the latest chapter into the hour record’s storied history. The chase for the elusive record generated mainstream headlines in the early 1990s amid a thrilling battle between Scottish rider Graeme Obree and British pursuit champion Chris Boardman.

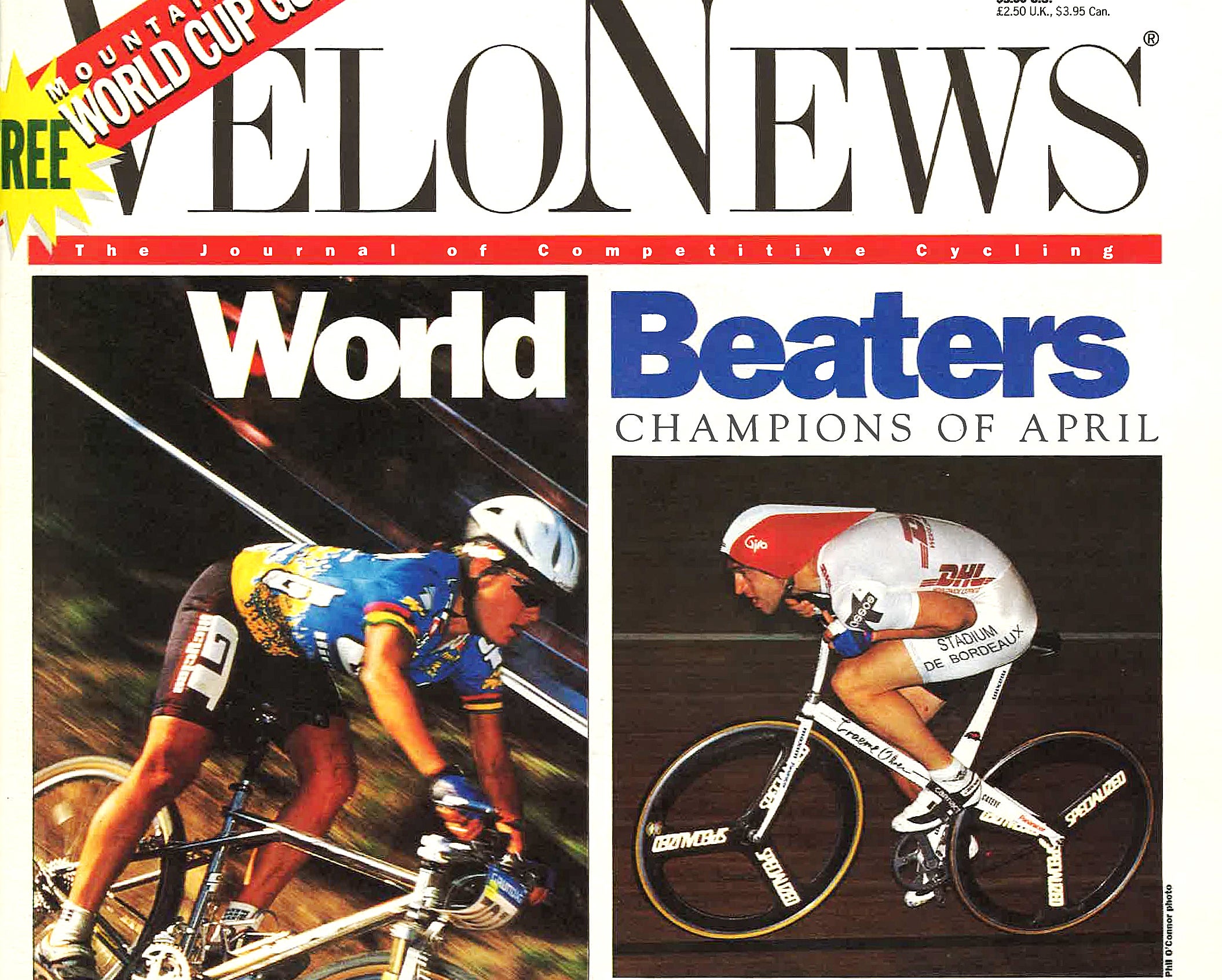

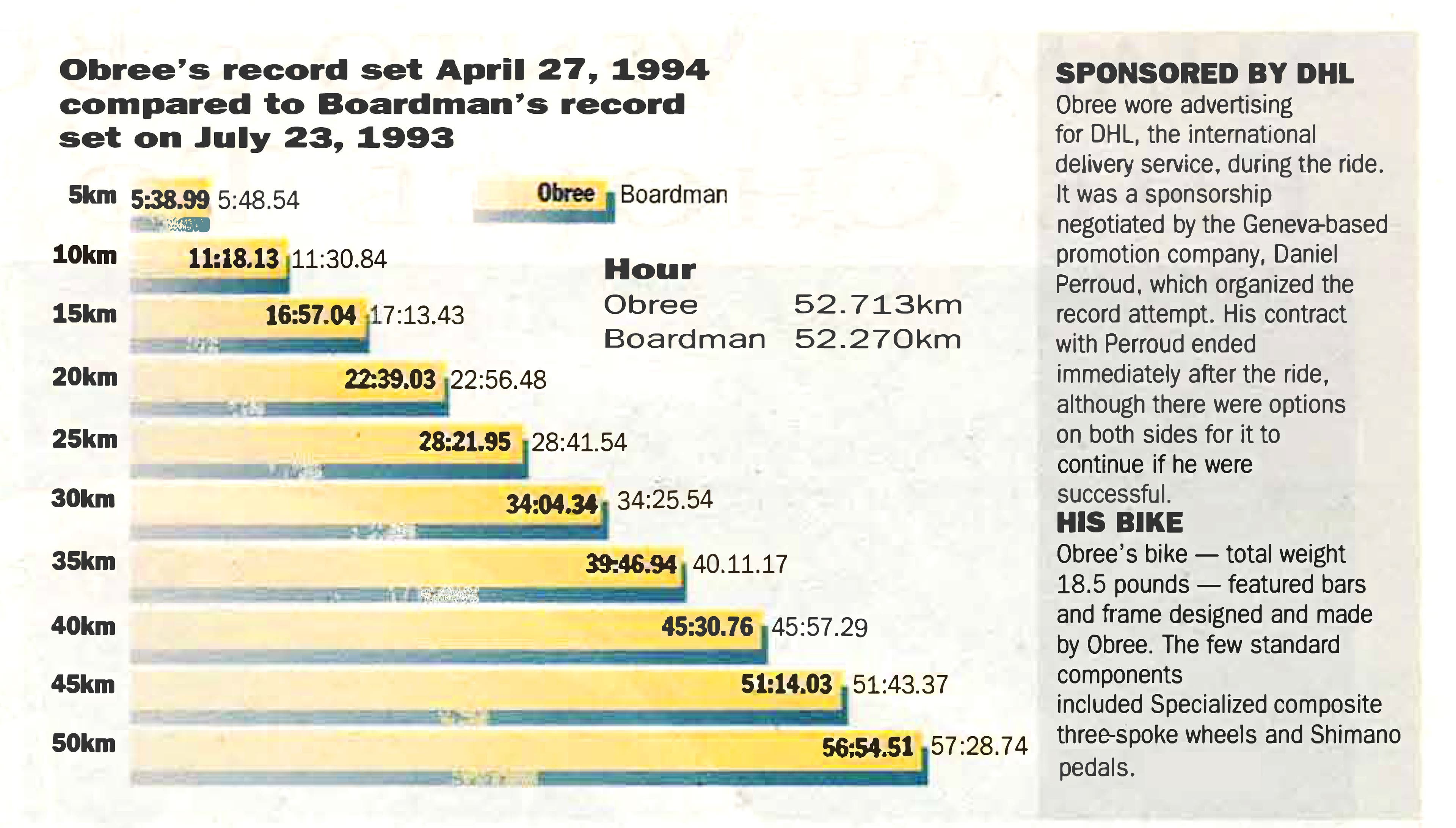

Riding his radical home-made bicycle, Obree smashed Francesco Moser’s hour record in July 1993, only to lose it six days later to Boardman. Then, on April 27, 1994, Obree again broke the record in Bordeaux, France, pedaling 52.713km in his trademark “Praying Mantis” style. One month later, the UCI outlaws Obree’s bicycle. This 1994 report from Martin Ayres, published in its entirety, takes us inside Obree’s record-setting ride in Bordeaux.

Obree’s finest hour: 52.713km!

In a remarkable display of sustained power, Scotsman Graeme Obree — using his hallmark tucked riding position for the last time — wrote another chapter in his remarkable saga when he regained the world hour record at Bordeaux on April 27, with a distance of 52.713 kilometers (32.753 miles).

Obree was unknown internationally until last July, when he ended Francesco Moser’s nine-year reign as hour record holder with a distance of 51.596km, in Harnar, Norway. Then, only six days later, the record was snatched from his grasp by England’s Chris Boardman, who was the first cyclist to break the 52km barrier — at the indoor velodrome in Bordeaux.

But Obree showed his mental resiliency by winning the world pursuit championship on his international debut last August; and last month, he headed for Bordeaux to bid for the most coveted record on the Union Cycliste Internationale books. Encouraged by good form in trial rides in Geneva, he declared his target would be the first 53 km ride … He missed that target, but succeeded in adding 443 meters to Boardman’s figure and improving his own previous best by 1.11 7km.

About 3,000 Bordeaux bike fans turned out to see the lone rider, who appeared in the track center five minutes before the scheduled 7 p.rn. start, and loosened his legs with several low-geared laps of the arena’s running track, riding a mud-spattered mountain bike. Meanwhile, the UCI commissaires were checking the dimensions of Obree’s controversial home-made bike.

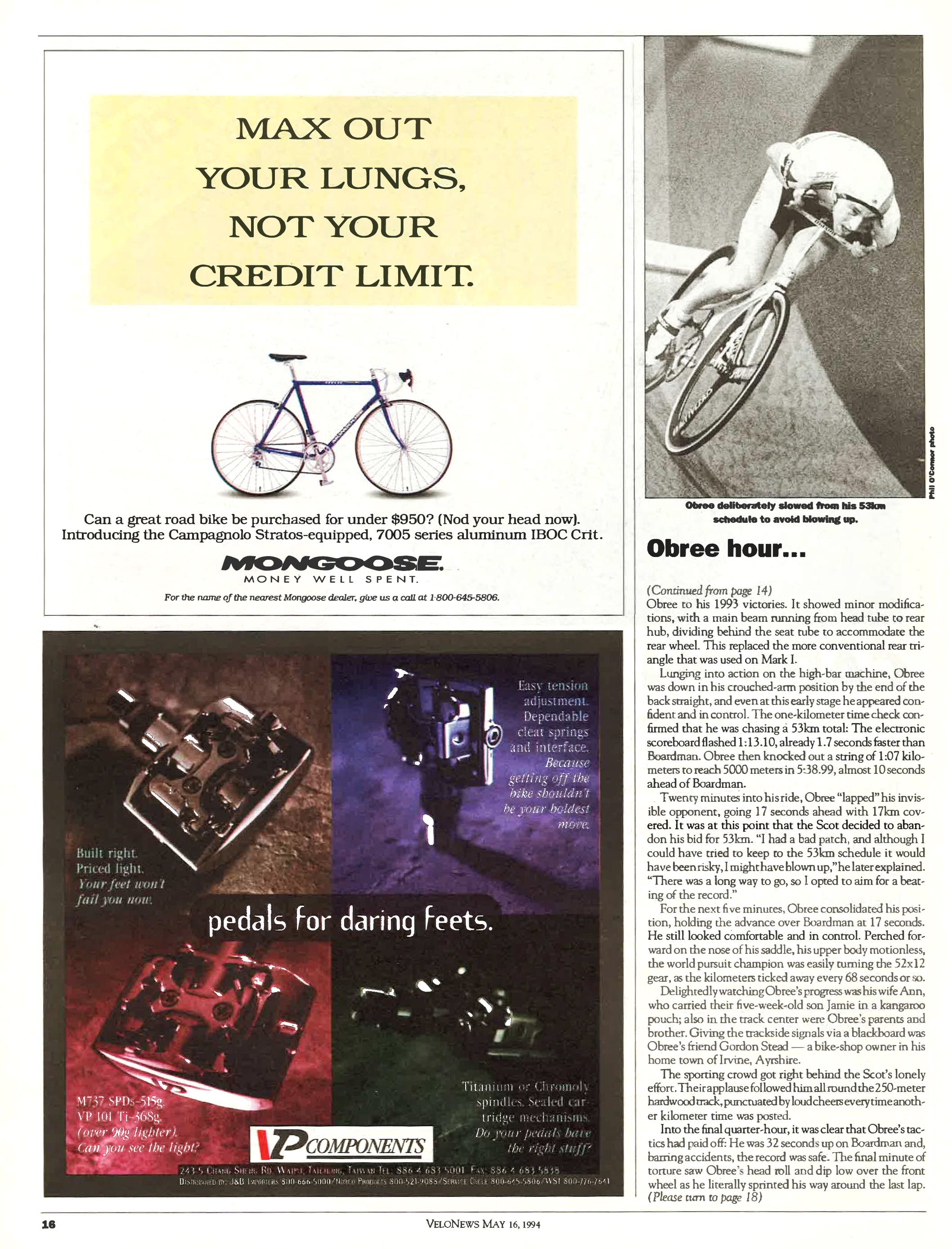

This was Mark II, successor to the machine that carried Obree to his 1993 victories. It showed minor modifications, with a main beam running-from head tube to rear hub, dividing behind the seat tube to accommodate the rear wheel. This replaced the more conventional rear triangle that was used on Mark I.

Lunging into action on the high-bar machine, Obree was down in his crouched-arm position by the end of the back straight, and even at this early stage, he appeared confident and in control. The one-kilometer time check confirmed that he was chasing a 53km total: The electronic scoreboard flashed 1: 13.10, already 1. 7 seconds faster than Boardman. Obree then knocked out a string of 1:07 kilometers to reach 5,000meters in 5;38.99, almost 10 seconds ahead of Boardman.

Twenty minutes into his ride, Obree “lapped” his invisible opponent, going 17 seconds ahead with 17km covered. It was at this point that the Scot decided to abandon his bid for 53km. “I had a bad patch, and although I could have tried to keep to the 53km schedule it would have been risky. I might have blown up,” he later explained. “There was a long way to go, so I opted to aim for a beating of the record.”

For the next five minutes Obree consolidated his position, holding the advance over Boardman at 17 seconds. He still looked comfortable and in control. Perched forward on the nose of his saddle, his upper body motionless, the world pursuit champion was easily turning the 52×12 gear, as the kilometers ticked away every 68 seconds or so.

Delightedly watching Obree’s progress was his wife Ann, who carried their five-week-old son, Jamie, in a kangaroo pouch; also in the track center were Obree’s parents and brother. Giving the trackside signals via a blackboard was Obree’s friend Gordon Stead — a bike shop owner in his home town of Irvine, Ayrshire

The sporting crowd got right behind the Scot’s lonely effort. Their applause followed him around the 250-meter hardwood track, punctuated by loud cheers every time another kilometer time was posted.

Into the final quarter-hour, it was clear that Obree’s tactics had paid off: He was 32 seconds up on Boardman and, barring accidents, the.record was safe. The final minute of torture saw Obree’s head roll and dip over the front wheel as he literally sprinted his way around the last lap. The gun fired, and at last he was able to straighten his back and salute the crowd.

Buried under a scrimmage of journalists, fans and TV reporters — the ride was shown live throughout Europe — Obree said: “The last 10 kilometers were the worst, I was afraid I might break, but I managed to hold on. The important thing is to get your name on the record books twice. I might even be lucky enough to do it a third time … if somebody breaks this record.

“This is the last time I’ll use this (high-bar) position in competition. Even if it is allowed after the UCI commission reports on May 6, I’ll still changeover to tri bars because people have this strange idea that anyone can break records using this position.

“Now I’m going to take a holiday, and then I’ve got to perfect this handlebar position — that is my overriding priority.”