Not all frames are created equal. A look deep inside the carbon in counterfeit bikes

Words by Logan VonBokel

Photos by Brad Kaminski and Chris Case

Parsons, a triathlete and former motocross racer, purchased his frame through DHGate.com, a website with the tagline, “Buy smart. Buy direct.” It insinuates that what you’re purchasing comes direct from the brands that are listed on its website.

But that $690 “Scott Foil Premium” frameset is not made by Scott. It’s not from the same mold as Scott’s Foil. The SL4 is not a real SL4. Both are fakes that have been reverse-engineered to be aesthetically similar pseudo-copies.

“I can’t afford a real S-Works. The replicas are just as good.” “They’re all made in the same factory in China.” “It’s the same mold.”

At Velo, we set out to ascertain how similar these counterfeit frames were to the authentic versions. Did they qualify as “replicas” — or deathtraps?

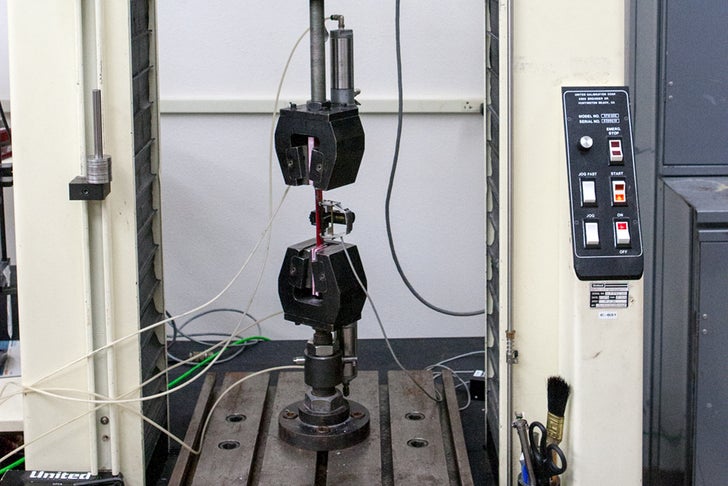

As we have in every VeloLab test, we enlisted the help of Microbac Laboratories. We asked them to examine Parsons’ counterfeit S-Works Tarmac SL4 and compare it to the genuine article — a 58cm 2014 Specialized S-Works Tarmac SL4.

The results are clear: The counterfeit is a poorly-executed, and dangerous, replica.

The test

The counterfeit Tarmac resembles the authentic SL4. The graphics are close, and if we did not have the real SL4 on hand to compare, we would have thought the counterfeit bike had a genuine Specialized paint job. The counterfeit seatpost, too, closely resembled that of the real SL4. However, and most importantly, upon close inspection of the frames, it was clear they are not the same. They are not even close.

First, the counterfeit frame did not come from the same mold as the SL4. If it had, the two frames would have identical geometries; they do not. No tube on the counterfeit frame is the same length as the real SL4.

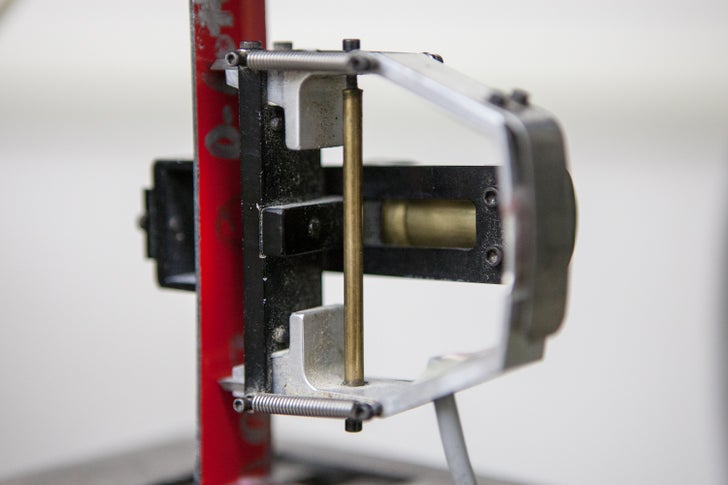

The construction of the headset was particularly worrisome. The genuine SL4 uses carbon cups integrated into the frame’s head tube, while the counterfeit uses alloy cups bonded into the frame. Specialized, which has its own testing facility, tested a similar counterfeit frame and found the alloy headset cups would not hold up to even the most elementary of destructive testing. It’s a claim that Velo and Microbac can confirm; the alloy cups in our counterfeit frame displayed considerable play as we secured the frame to the testing jig.

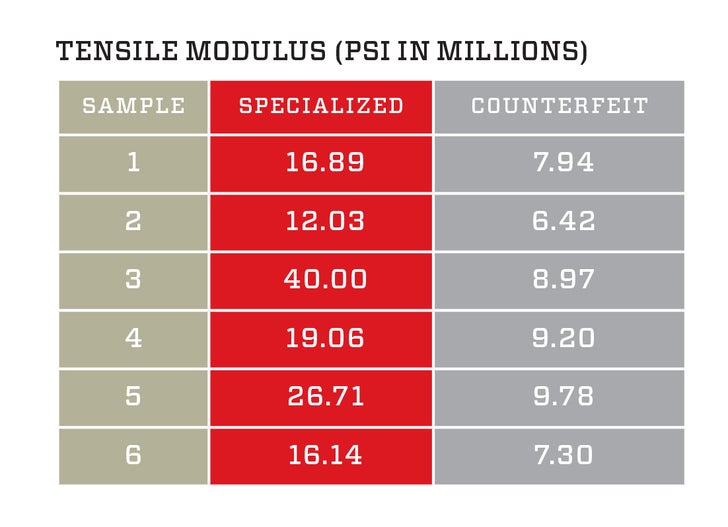

To some, the difference might sound negligible; however, Steve Ferry of Microbac said, “I think it is a noteworthy difference.” In this game of high performance and marginal gains, 11 percent is a substantial figure.

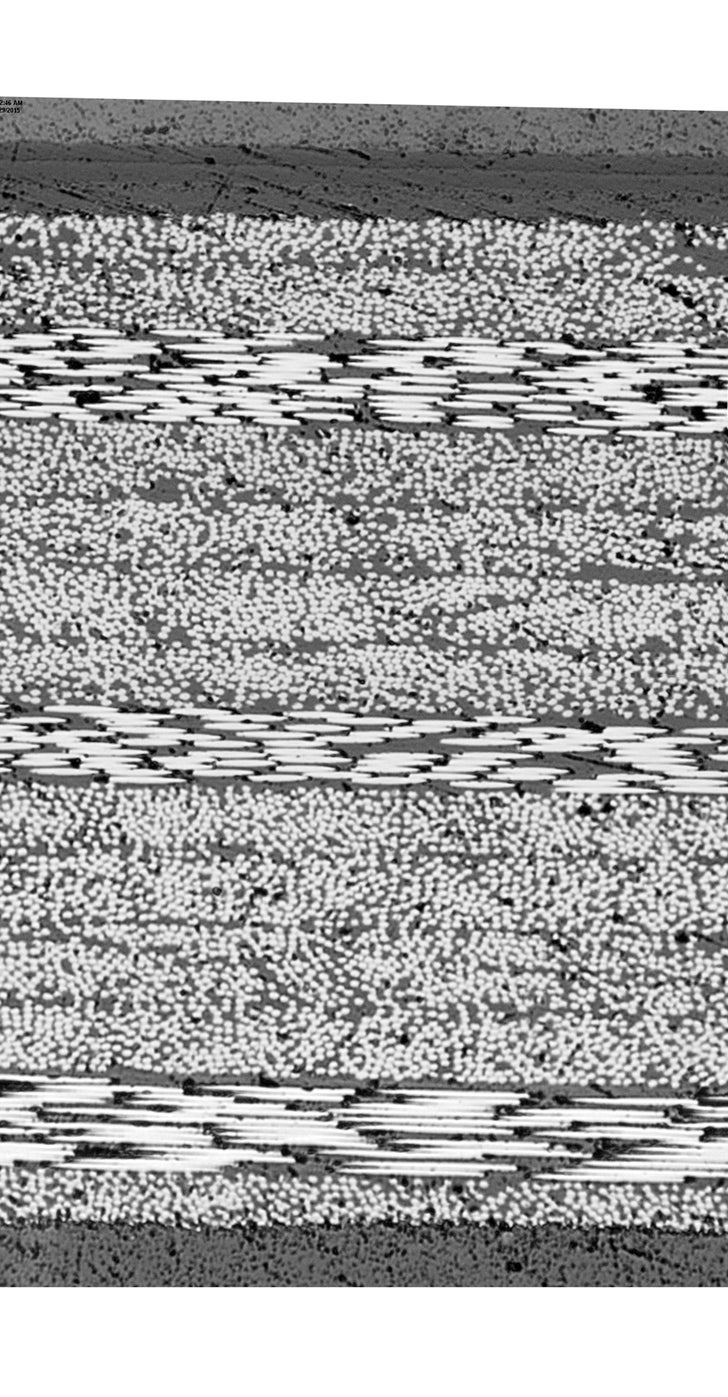

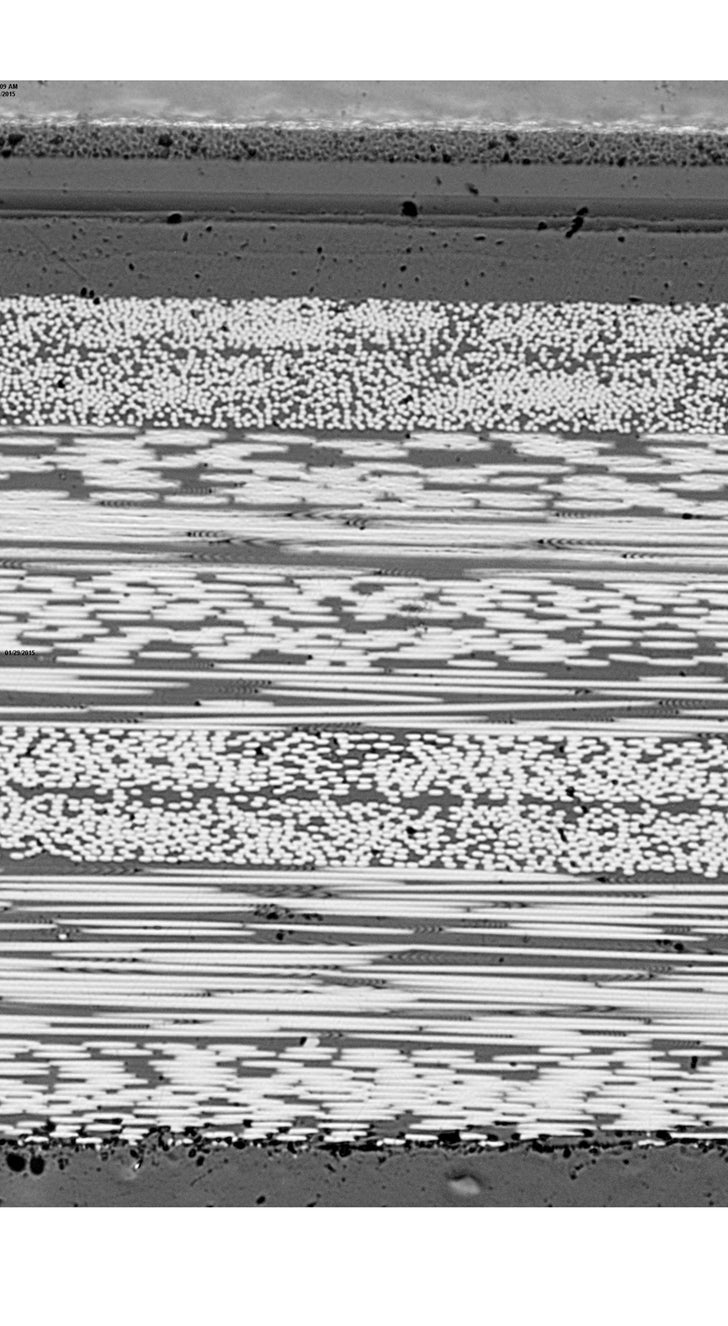

Each frame had sections cut out of the top and bottom of the top tube, as well as out of the top, bottom, left, and right of the down tube. The strength of each cutout was individually tested, and this is where the differences of the frames were magnified. The Tarmac is engineered to ride like a high-performance bike; the counterfeit is designed to simply look like a Tarmac.

“In total, this indicates an engineered approach to tune the ride in the Specialized, and just a blunt force approach with the counterfeit,” Ferry said. “They’re just slapping stuff into the mold. If you look at thickness, yield strength, and modulus, the Specialized is much more varied [from tube to tube as well as within each tube] and there is little difference in the counterfeit.”

If it’s too good to be true …

The websites that sell the counterfeit frames appeal to the deal-savvy consumer. In the world of cycling, where exorbitant prices seem to become more commonplace by the season, the attraction is understandable. Unfortunately, the repercussions can be tragic.

“The [S-Works] frame I wanted was $3,500, and over there it was $700. I believed they were using the same molds,” Parsons said of the counterfeit frame he purchased. “There is no scenario [where] I could recommend a knockoff frame to anyone. They’re terrifying. At minimum, it will result in a terrible crash.”

The sellers, mostly from China, seem to be unconcerned with the safety of their product, or the customers who fall for the fakes. Parsons’ pleas to return the frame went unanswered. “I think they strung me along just long enough so that I couldn’t get my credit card [bank] to cancel the transaction, but this was after all the headaches just to get the bike in my hands,” Parsons said.

As with most things, if the price tag looks too good to be true, it likely is. Don’t be the sucker who falls for it.

– Second image from the top: fake

– Third image from the top: Left is real; right is fake.

– Two head tube images: Frame on right is fake in both.

– Splintered carbon image above: fake

This article was originally published in the April 2015 issue of Velo magazine.