New report presents data-driven doubts on performances, past and present

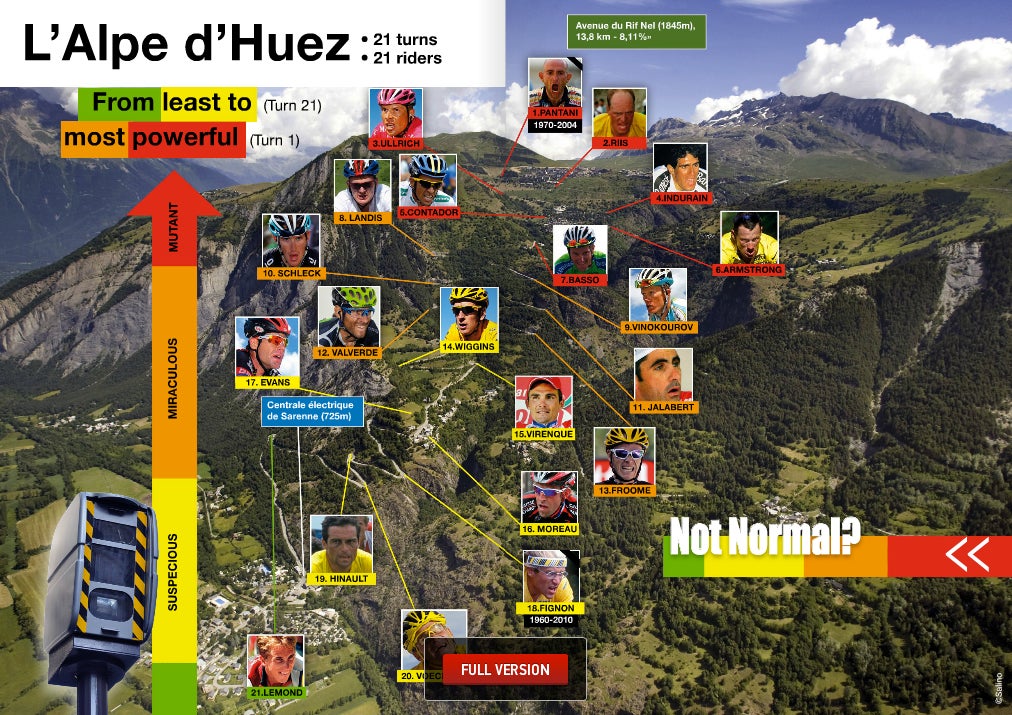

A page from Not Normal?, analyzing 21 performances on L'Alpe d'Huez

“Not Normal.” It’s what Lance Armstrong supposedly said about his rivals who were turning in performances beyond the realm of natural human possibility. Doing things that just weren’t natural.

Now, it’s the name of a new digital publication that takes aim at 21 of the sport’s top riders from different eras, and analyzes performances, in watts generated up climbs at the end of long days within stage races.

Not Normal? An insight into doping and the 21 biggest riders from LeMond to Armstrong to Evans examines riders both old (Bernard Hinault) and new (Chris Froome, Bradley Wiggins), and labels performances across an index of suspicion versus believability.

It’s the result of years of research by its editor, Antoine Vayer, a French journalist and a Festina trainer from 1995 to 1998 who has written for French dailies Le Monde, Libération, and l’Humanité.

In 1999, Vayer created AlternatiV, an independent organization aimed at helping athletes who either chose not to dope, or hoped to quit using PEDs. Last year, he joined the action group Change Cycling Now.

Vayer worked closely on Not Normal? with a team of three French contributors. Frédéric Portoleau, a software engineer, contributed the power calculations in watts for the scientific section, and wrote some of the commentary in Not Normal? Stéphane Huby, who manages cyclisme-dopage.com, a site devoted to doping in cycling, contributed to rider sections of the magazine. Jean-Pierre de Mondenard, a French sports doctor who has been the official doctor for the Tour de France (1973-1975), also contributed to the publication.

The report looks at data, but also contextualizes it with graphics, essays and articles, and collections of quotes about each rider being scrutinized — sometimes from the rider himself.

Findings were generated via calculations — many of the performances took place before the advent of power meters — but according to the report, and a side-by-side analysis of actual power data from Chris Horner (RadioShack-Leopard), the wattage numbers are close.

The authors claim their projected data comes in at about one-percent higher than actual watts generated by Horner on marked climbs, though one measurement differs by as much as 9 percent, up the west Tourmalet ascent, so it’s important to take the metrics with a grain of salt.

Compression wear company Skins — whose chairman, Jaimie Fuller, fronted the cash to launch Change Cycling Now, has voiced his opposition to UCI president Pat McQuaid, and funded a suit contesting McQuaid’s candidacy for a third term as UCI president — funded the publishing endeavor. (It’s available as a $10 paid download here.)

In short, the findings aren’t particularly kind to many of the riders, and generally indicate what most keen observers already suspected: most great rides, according to the publishers, are slightly suspicious at the very least, and can veer into superhuman performance.

“Antoine explained to me how everybody focuses on the doping when considering PED’s (performance enhancing drugs) and very few look to the performance as a marker of doping,” Fuller wrote in the 148-page document. “Along with his team, Antoine has created a fascinating study of 21 riders’ power output on mountain stages over 30 odd years and this magazine is the culmination of their hard work.”

Rider performances on iconic climbs in cycling, mostly used during the Tour de France, are classified into different performance labels: green, which means that the authors view the performance as unremarkable as far as suspicion is concerned; yellow is suspicious; orange is miraculous; and red is labeled as off the charts.

As an example, the chart that’s affixed to Marco Pantani highlights performances in mostly red, meaning his output levels are, in the eyes of the authors at least, “mutant.” The data presented indicates that in 1994 Pantani rode up the Hautacam climb, at 24 years of age, at a “standard” power of 465 watts, or an astonishing 7.05 watts per kilogram.

Not Normal? is kindest to three-time Tour winner Greg LeMond, a member of Change Cycling Now; most of his rides appear in green, and only three appear in yellow, or as “suspicious” — a climb up Avoriaz in 1984 while chasing Hinault, and the rides up Superbangnères and Izoard in the 1989 Tour.

Thomas Voeckler, Hinault and Wiggins fall into Not Normal’s suspicious category; Chris Froome, Andy Schleck and Laurent Jalabert into the miraculous; Alberto Contador, Miguel Indurain, Jan Ullrich, and Lance Armstrong fall into the mutant classification on some performances, or had at times in their careers.

The publication has mountains of data collected by Vayer and his team. What it doesn’t have is concrete proof of wrongdoings. This, Vayer writes, doesn’t matter.

“Forget ‘I never tested positive.’ It needs to be replaced by ‘I was never clocked by a radar doing 430 watts standard in the final col of a long mountain stage.’ It’s utterly more convincing. You’ll understand why, by reading this magazine. It’s just as convincing as the thousand-page U.S. Anti-Doping Agency report revealing the Armstrong scandal and just as convincing as the police and customs investigations which brought to light and brought to justice the ‘Festina’ and ‘Puerto” scandals. The proof of the hoax lies in performance analysis and interpretation.”

In an interview with VeloNews this week, Vayer said Not Normal? was the summary of 15 years of work. “It’s a huge work,” he said. “We must resolve the past. We must talk about the past,” he said.

The publication gave riders a chance to describe their performances. Most riders in the magazine elected not to respond. Voeckler (Europcar) was one who did. He wrote:

“This is not the first time people wonder about my performances and I can conceive it, even if it hurts, because I sometimes doubt myself about those of some riders. However, I am quite surprised that this questioning is built, as often, on uphill cycling timings or power ‘calculations,’ because it seems logical that the actual power developed by a [rider] can not be exactly known unless the bicycle is equipped with a device aimed to measure power,” he wrote, adding that the calculations, in his opinion at least, failed to account for racing factors, such as slipstreams.

“My goal is not to try to convince all the people who are asking questions about me or my integrity. My goal is and always has been to achieve the best possible results according to my ethical beliefs, [which] do not tolerate doping, and if this state of mind has allowed me sometimes to beat cheaters, many times it is the latter which deprive honest [riders] victories, or at least distort the race,” he wrote.

According to the authors, Froome’s performances should elicit more scrutiny than those of Wiggins. Team Sky responded to questions regarding Wiggins and Froome asked by the publication with a statement:

“Both Chris and Bradley have received your email and each has considered their response. They have been asked many times before about their stance on doping and their approach to performance. It’s all already firmly on the record; neither has used banned substances or illegal practices. Team Sky’s approach to conditioning and coaching is also well documented. We know exactly how our riders prepare and perform and the true science behind this. And we have our own accurate data that we can rely on to support this.

“Given the sport’s past, everyone understands why questions are asked and performances constantly debated. It’s understandable but a real shame when good clean rides, that should be admired, are doubted routinely,” the team statement continues. “Quite simply, we’ve had a clear anti-doping stance from the start, are a clean team and our riders have shown that you can win clean.”

Fuller said the numbers were just one more element to consider, and that cycling wasn’t yet rid of its unfortunate past.

“We should never be scared of the truth,” Fuller told VeloNews. “It’s been worrying me for a while now, some of the comments that we’re hearing, ‘and the new guys don’t dope…’ you’d have to be pretty fucking stupid to believe that, after having gone to the ‘Tour of Renewal,’ in 1999, after Festina.”

That said, Fuller thinks the lower numbers, and more “green” in the report, indicate a cleansing sport.

“This is just another marker, albeit a significant one, that should help the people in the game doing what they’re doing,” he said. “The signals are good. I’m really pleased … I’ve said to a couple of people, this is something good for [UCI president] Pat McQuaid.”

For his part, Vayer also believes the sport is cleaner than it was. “Yes, cleaner, I think,” he said. “It is a sport, not only a show … if cycling could be in green, it would be fantastic. It would be the most fabulous sport we’ve ever seen.”

“I will have my own opinion … But it is better… better is not the right word, it is less worse.”