No doping cases in the 2021 WorldTour: Reason to celebrate, or time to worry?

Tramadol will be banned by WADA starting in 2024. (Photo: Doug Pensinger/Getty Images)

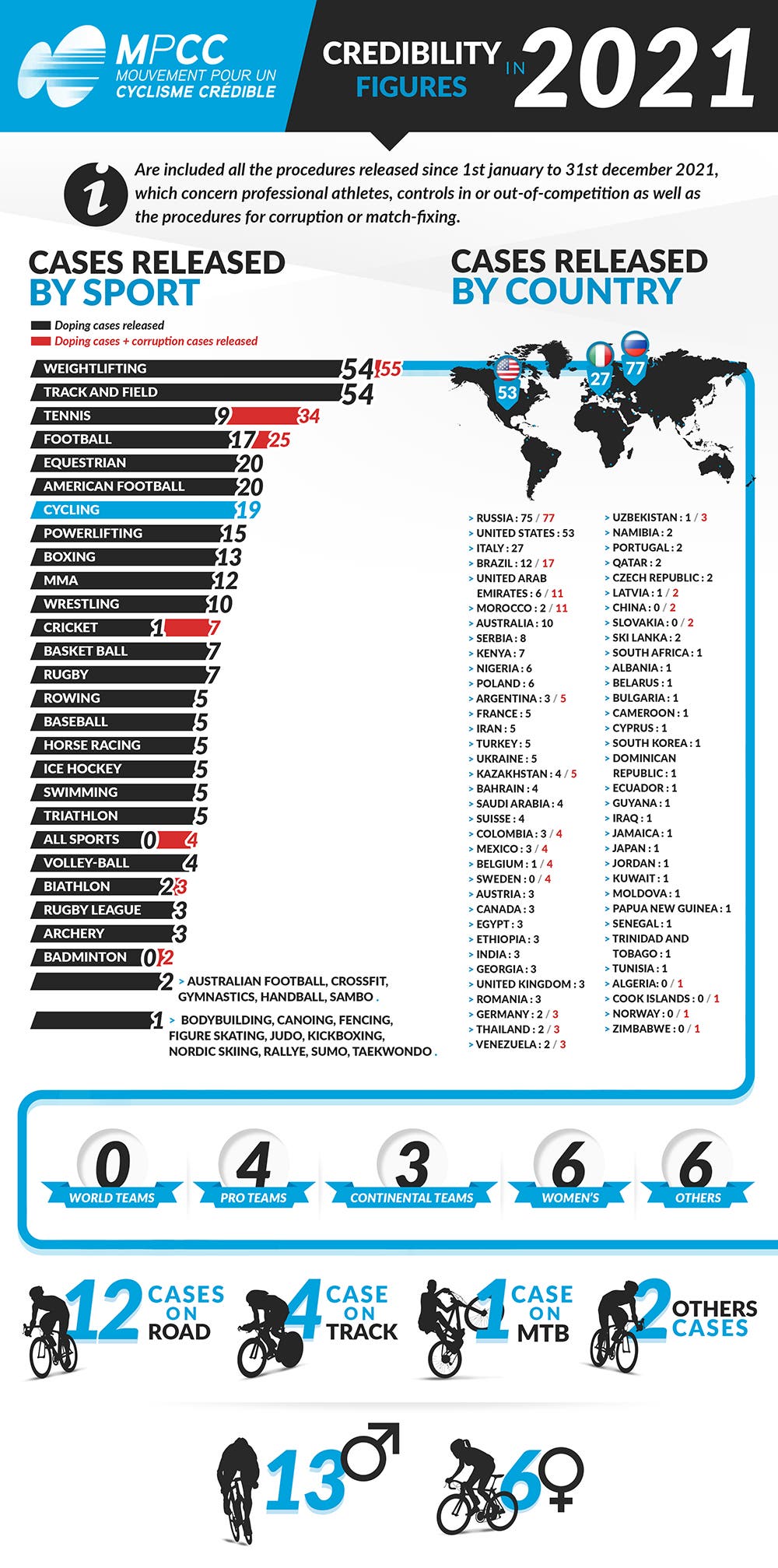

The MPCC released an eye-catching statistic over the weekend: there were no reported doping violations within the men’s WorldTour in 2021.

That marks the first season since the WorldTour was created in 2005 without a doping case.

In a sport long associated with doping scandals and lurid headlines, an entire season without one anti-doping violation at the elite of the men’s peloton surely should be a reason to celebrate, right?

The MPCC — Movement for Credible Cycling — isn’t so sure.

The advocacy group, which represents a handful of WorldTour and ProTeam squads, said the statistic is not something to rejoice.

“For the first time since its creation in 2005, the WorldTour division recorded no doping cases last year,” a statement read. “Some stakeholders and managers are not delighted about this news.”

Also read: Guillaume Martin joins chorus of riders voicing concern over ketones

As the peloton continues to produce one jaw-dropping performance after another at the Tour de France and other major races, the fact of not having a doping case in its own way raises questions for some about the integrity and efficiency of the anti-doping system.

It’s a double-edged sword. If there are no doping cases, does that mean the peloton cleaned up its act? Or are the cheaters one step ahead of the anti-doping authorities?

Nagging worries of a ‘peloton at two speeds’

Some inside the cycling community are reviving concerns about a “peloton at two speeds.”

That refrain dating back to the EPO Era describes a peloton split by teams and riders on each side of the doping divide, and some are worried it has the same currency today as it did in 1999.

There’s no question that riders are racing faster, deeper, and more brilliantly than ever.

Also read: Cortisone controls put MPCC into spotlight

Some insiders defend today’s peloton as perhaps the cleanest the sport’s ever been, and insist advancements in such things as coaching, technology, aerodynamics, and nutrition helped push the sport to a new, cleaner level.

It’s not all roses, and cycling still saw its fair share of doping cases in 2021.

The MPCC cited 12 cases involving road racing in 2021 among non-WorldTour teams for a total of 19 anti-doping violations across all disciplines in men’s and women’s racing last season.

Critics insist that the peloton remains rife with performance-enhancing drugs (and motors), and that cheaters are using more sophisticated methods that can bypass established anti-doping protocols.

Some believe that micro-dosing, the application of non-banned substances and practices to enhance performance, and even the adaptation of new products that evade existing anti-doping controls continue to be abused within the peloton.

The MPCC wrote that “performances from emblematic riders once again point to a ‘two-speed’ peloton,” and said that the organization supports recent suggestions by the UCI’s No. 2 to push for more intelligence gathering.

Amina Lanaya, the UCI’s executive director, recently admitted that even the UCI is worried, and said that doping controls alone are not enough to unmask the cheaters in professional cycling.

Lanaya, speaking in a recent interview with Ouest-France, said anti-doping authorities need to dramatically enhance intelligence work, strengthen cooperation with police and other legal authorities, and even perhaps use inside-the-bunch paid informants in order to stay a step ahead of would-be dopers.

“Doping controls, for me, are no longer the main source in the fight against doping,” she told Ouest-France. “Today, everything happens with intelligence, investigation, and cooperation with police.”

Lanaya said the cycling governing body and anti-doping authorities must work more closely with sources, intelligence gathering, and police to try to catch up with ever more sophisticated would-be dopers.

“The cheaters have an advantage,” she said. “They know [how long] a substance can be detected. We need information from inside the peloton, so we can trigger night-time testing if someone is micro-dosing.”

Lanaya even suggested that using paid informants inside the peloton could be a powerful tool to help police and anti-doping authorities to track and target test suspicious riders.

“When we start to have positive cases with people who believe they are untouchable, word will get around,” she said, quickly adding that paying informants might not be legal.

Lanaya’s comments were enthusiastically endorsed by the MPCC, whose members abide by a stricter code than one required by WADA.

“According to Amina Lanaya, more radical methods of investigation should be considered,” wrote the MPCC. “The MPCC fully supports this approach.”

Lanaya’s comments, made to Ouest-France in an interview earlier this month, did not go down well with Gianni Bugno, the ex-pro who runs the UCI-recognized rider’s group CPA.

Speaking to La Gazzetta dello Sport, Bugno — who emphasized he was speaking of his personal point of view and not an official position of the CPA — said he was not happy to read those comments.

“Statements like this, on the part of the UCI, are not pleasant. They put a serious question mark on the whole system,” he told La Gazzetta. “It seemed that the doping problem was being resolved, but if you evaluate actions of that type it means that you are not so convinced. … We are talking about sport, not a crime.”

Riders ‘trust each other, trust the process’ for anti-doping efforts

What do riders think?

If one believes the argument that the peloton’s undergone a cultural shift away from relying on PED’s, today’s performances seem credible, especially in light of a younger, perhaps untarnished generation taking hold.

One top WorldTour pro, speaking anonymously to VeloNews, said today’s generation of pros do not suspect the performances of their peers in the same way riders did a decade or two before when EPO and blood doping were rife in the peloton.

“I think for the majority of pro riders in the peloton, the last thing they’re worried about is if someone is doping or not,” the rider told VeloNews. “It’s very rare that we ever question a performance by someone. It [doping] just doesn’t seem necessary anymore to have success in the sport. We trust each other, and we trust the process.”

So where do anti-doping efforts stand today?

Riders remain under the vigilance of doping controls during and out of competition, as well as have to undergo quarterly health checks and provide daily whereabouts information to authorities.

Anti-doping samples are also stored for years to be open for additional testing when new techniques or intelligence becomes available.

There is also the sensation that anti-doping efforts are under-funded and under-staffed, giving well-heeled teams and riders a financial head start.

Some whispered that surprise anti-doping controls declined sharply during the worse of the COVID-19 pandemic, opening a new door of opportunity for would-be cheats.

Also read: UCI’s anti-doping efforts folded into ITA

Lanaya’s comments come one year after the UCI switched its anti-doping efforts from an independent body to be part of the International Testing Agency, a larger umbrella group working across several international sports federations and the International Olympic Committee.

UCI president David Lappartient decided to fold the UCI’s independent anti-doping arm into the ITA, a move that drew some criticism.

Lappartient argued that being part of the larger group ITA would give cycling more tools in its toolbox to fight would-be cheaters.

Last week, the UCI released a media note to highlight a recent audit by the World Anti-Doping Agency of the UCI’s efforts since the ITA transition, adding that the audit “confirmed the strength and quality of the UCI’s anti-doping program.”

Last year, UCI officials underscored that intelligence work and cooperation with police are ongoing under its transition to the ITA.

Hints of how police at least in France are keeping tabs on the professional peloton burst into public view during two recent editions of the Tour de France.

In 2020, French police searched the hotel of French team Arkéa-Samsic. And last year, French authorities searched the bus and hotel of WorldTour team Bahrain-Victorious as well as confiscated the smartphones and computers of some riders and staffers.

Neither of those raids resulted in formal charges against any cyclists or teams in France, where doping in sport is equivalent to a felony offense.

Throughout cycling’s long and lurid history with doping, it’s often been the involvement of police and courts that’s delivered the most meaningful punch.

If the UCI and anti-doping authorities are indeed working more closely with police and intelligence sources, next year’s report might see different results, at least if one takes the cynical view.