It isn’t a surprise that Tadej Pogačar won the Critérium du Dauphiné. But it is surprising how it happened.

First, Pogačar won the opening stage in a sprint after a late-race breakaway. Then, Pogačar lost nearly a minute in the time trial thanks to a baffling performance. Three stages later, the world champion had turned the tables to win the GC by a minute and put nearly five minutes into Remco Evenepoel who last year finished third at the Tour de France.

How did that happen?

Rewind back to stage 1, and cycling fans knew we were in for a treat of a race. Jonas Vingegaard attacked over the crest of the final climb, creating a four-man breakaway with Pogačar, Santiago Buitrago, and Mathieu van der Poel. Evenepoel bridged across shortly thereafter, and the group of five came into the final kilometer only a few seconds ahead of the peloton.

MvdP led out the sprint, giving Pogačar and Vingegaard the perfect slingshot to come around him, and it was Pogačar who took the win. The big four were in flying form, and the stage was set for an excellent Dauphiné.

Jonathan Milan won stage 2 in a sprint, while Iván Romeo took a surprise victory when the breakaway held off the peloton on stage 3. But the real statements came during stage 4’s time trial.

On a relatively short course of 17.4km, we weren’t expecting major GC gaps. In fact, Evenepoel winning was exactly what many expected. Vingegaard finishing second was certainly an impressive ride, but 28 seconds further down in the results was Pogačar.

The questions begin here: why was Pogačar so far off the pace? Was Pogačar riding all-out? Why did Pogačar inspect Visma-Lease-a-Bike’s Cervélo time trial bike after the race?

Part of me believes that this year’s Critérium du Dauphiné was one big game of poker. The top riders – Pogačar, Vingegaard, and Evenepoel – were showing their hands one day, and bluffing the others. As we dive into the numbers, their performances are too inconsistent for any other explanation. Of course, it was hot and Evenepoel mentioned something about allergies. But at this level of the sport, these riders should not see significant changes in their peak 10-30 min power over the course of 4-5 days.

First, let’s take a closer look at the time trial. The first 6.5 km of the TT was completely flat. Thus, a rider’s speed is determined by their watts per CdA (coefficient of aerodynamic drag). Evenepoel is the fastest rider in the world using this calculation.

Pogačar has been improving his TT ability for years, and he is typically one of the fastest time trial riders in the world. But in the first 6.5 km of stage 4, he was 25 seconds slower than Evenepoel.

Next up was the punchy climb, which was a 4-5 minute effort with gradients up to 18%. Evenepoel was still faster than Pogačar on this section of the course, but only by a few seconds. The Slovenian continued losing time to Evenepoel over the second half of the course, shipping 48 seconds to the world time trial champion in just 17.4 km.

In hindsight, the stage 4 results are still baffling. There can only be a few possible explanations. Either Pogačar wasn’t riding all-out, or there was a problem with his bike. Team UAE Emirates-XRG’s TT setup has been exceptionally fast over the past few seasons, so there shouldn’t be any reason that the bike is suddenly slower.

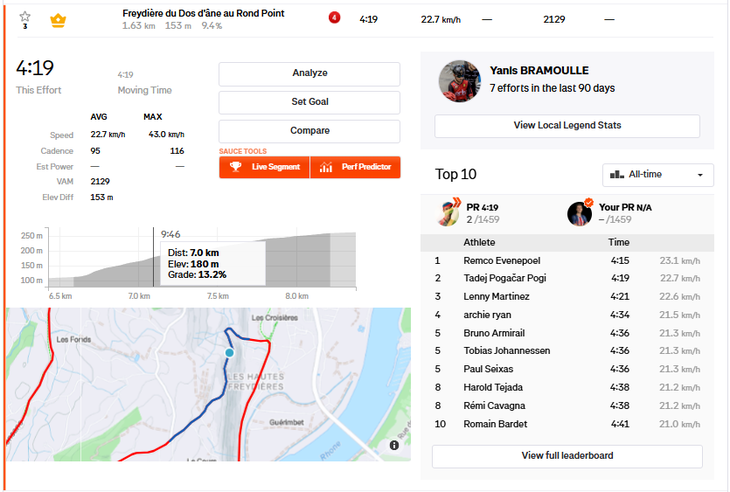

Pogačar and Evenepoel rode up the TT climb at just over 2,100 vertical meters per hour for four minutes. Less than 48 hours later, Pogačar would obliterate that pace on a much harder and longer climb.

Though we don’t know why, Pogačar clearly wasn’t riding all-out in the time trial.

Pogačar – Stage 4 TT Climb

- Time: 4:19

- Estimated Average Power: ~510w (7.9w/kg)

- Evenepoel: 4:15 at ~8w/kg

Jake Stewart took an impressive win at the end of stage 5, and then it was back to the mountains for stage 6 of the Dauphiné. The final few stages of the race were exceptionally short, weighing in at 127 km, 132 km, and 133 km, respectively. Each stage would only last 3-4 hours, which could favor some riders over others.

Some believe that the longer and harder the race, the smaller the performance gap is between Pogačar and Vingegaard. The world champion seems to have the edge during shorter, punchier races. Whereas Vingegaard shines during longer and harder efforts. In fact, the only times that the Dane has cracked Pogačar were at the end of a long and hard mountain stage in the third week of the Tour de France.

Nevertheless, we are here for the Dauphiné, and stage 6 was all about Pogačar. His team led him out from the bottom of the final climb to Combloux, and it was only a matter of minutes until Pogačar left everyone behind. The world champion went on to win the stage a minute ahead of Vingegaard, and 1:22 ahead of Florian Lipowitz (remember the name). Evenepoel was nearly two minutes down.

What I find so interesting here is how hard Team UAE Emirates-XRG rode the first few minutes of the climb. Pavel Sivakov was pushing 8w/kg during his final leadout for Pogačar, and then the world champion accelerated off of that pace.

By the time Pogačar crossed the finish line, he had done an estimated 7.1w/kg for 20 minutes. An impressive effort, of course, but far from his level of nearly 7w/kg for 40 minutes at last year’s Tour de France. Yet, the gaps behind Pogačar were massive.

Pogačar – Stage 6 Climb to Combloux

- Time: 19:26

- Estimated Average Power: ~460w (7.1w/kg)

- First 6 min of the climb: 2,187 Vm/h at ~7.7w/kg

A few things could be happening here. One is that Vingegaard and the others could have blown up as a result of Team UAE’s leadout. By riding at ~8w/kg for the first six minutes, Pogačar and his team put everyone into the red, forcing them to go above their limits and into oxygen debt. With 14+ minutes of climbing to the finish, there was nowhere to hide, and riders began bleeding time.

Another option is that Vingegaard was bluffing, refusing to show his true level until the Tour de France. The Dane could have followed Pogačar’s initial attack to gain valuable performance data — how long does Pogačar attack for? What power output do I need in order to follow him? — and once the data was gathered, backed off.

In the end, Vingegaard only finished 21 seconds ahead of Lipowitz, 29 seconds ahead of Matteo Jorgenson, and one minute ahead of Louis Barré, Ben Tulett, and Paul Seixas. With all due respect, Vingegaard in peak form would be putting a lot more time into these riders on a steep 20-minute climb.

The GC showdown continued on stage 7 with the queen stage from Grand-Algueblanche to Valmeinier 1800. There was 4,800 meters of climbing packed into the 132 km stage. First up was the 24.7km Col de la Madeleine, next was the 22.4 km Col de la Croix de Fer, and the stage finished on the 16.2km Valmeinier 1800.

Though we didn’t see the first half of the stage, we can see via Strava just how hard each climb was ridden. Visma-Lease a Bike kept attacking and splitting the race, putting riders up the road and even pushing the pace on descents. Pogačar weathered each storm, but his teammates couldn’t handle the pace. So with 62km to go, Pogačar was completely isolated at the front of the race.

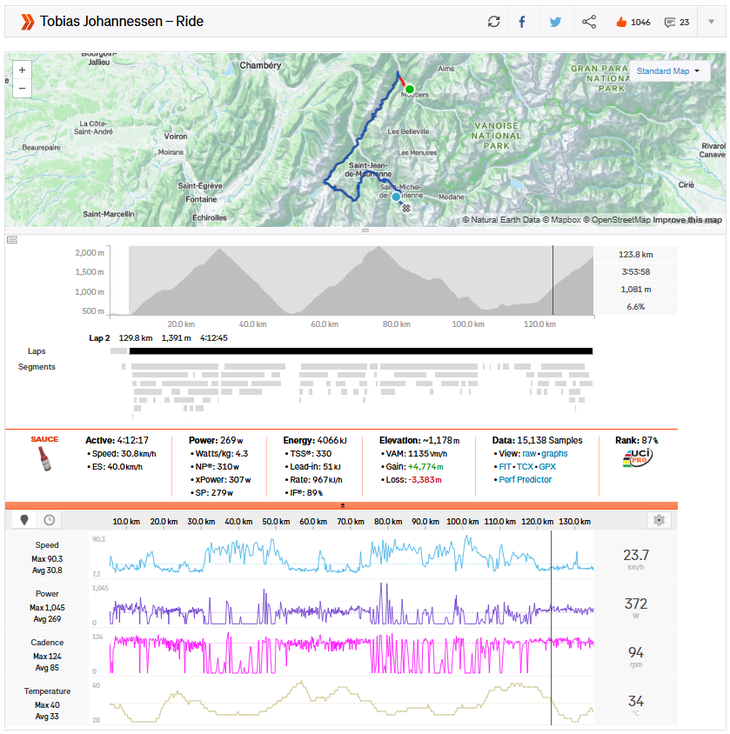

Tobias Johannessen had an excellent Dauphiné, with stage 7 being his best performance. The Norwegian was able to stay with the lead group on each of the first two climbs, and then with Evenepoel on the Valmeinier 1800. Johannessen posted his power data on Strava, so we can see exactly what it took to race with the favorites at the Dauphiné.

Attacks came and went in the valley to Valmeinier 1800, but the peloton started coming back together before the base of the climb. Crucially, Sivakov came back to the lead group, and he would be Pogačar’s only teammate at this point of the race.

Sivakov helped pace in the valley and for the first few kilometers of Valmeinier 1800, but then Sepp Kuss launched a serious attack. Instead of jumping onto his wheel, Sivakov began setting a ferocious pace on the front of the peloton. The group was shrinking by the second as Sivakov began pushing over 500w. With 12 to go, Sivakov pulled off and Pogačar attacked. Vingegaard only held his wheel for a few seconds, and no one else was even close to Pogačar. This is where things got weird again.

Vingegaard was dropped with 28 minutes of climbing to go. Normally, you would think that someone who gets dropped here would continue to lose time, especially to a rider like Pogačar. But Vingegaard kept the gap stable. Pogačar‘s lead never grew to more than 30 seconds, despite the fact that Lipowitz, Evenepoel, Johannessen, etc., continued to lose time to Pogačar.

Johannessen – Stage 7 Climbs

- Col de la Madeleine: 1hr 5min 14sec at 5.4w/kg

- Col de la Croix de Fer: 1hr 5min 41sec at 5w/kg

- Valmeinier 1800: 39:38 at 5.5w/kg

Pogačar – Stage 7 Final Climb

- Valmeinier 1800: 37:12 at ~6.5w/kg

The yellow jersey said he slowed down in the final kilometer, but he was certainly pushing himself during the climb. You can tell from his breathing and belly when Pogačar is really pushing. The Slovenian has an excellent poker face — he never grimaces when he attacks, despite the pain that he’s inflicting on his legs. But when he is really pushing, you can see his belly rapidly expanding and contracting due to his rapid breathing rate.

Pogačar also put nearly three minutes into Evenepoel, four minutes into Enric Mas, and over five minutes into Jorgenson. These riders were fighting for a top-10 in the Critérium du Dauphiné, so they were certainly pushing with everything they had. The first section of the Valmeinier 1800 wasn’t ridden full gas, and then Pogačar slowed down in the final kilometer. So during his attack, he was probably pushing close to 7w/kg, despite the overall climbing time being closer to 6.5w/kg.

Pogačar – Valmeinier 1800

- First 6 km: ~5.6w/kg

- Middle 11 km: ~7w/kg

- Final Kilometer: ~5.7w/kg

The final stage of the Dauphiné featured an uphill finish at Plateau du Mont-Cenis, and there wasn’t much to write home about in terms of the GC. The top five remained unchanged, and Pogačar and Vingegaard finished together, just behind the stage winner, Lenny Martinez.

Looking back at this Dauphiné, I’m not sure I can confidently say that we learned much from it in reference to the Tour de France. In stage 4, Pogačar was terrible, Vingegaard was outstanding, and Evenepoel was even better. Two days later, Pogačar crushed them both, Vingegaard was far from his best, and Evenepoel was even worse.

By the end of the race, Evenepoel was the fifth-best climber in the race behind Lipowitz and Johannessen. Do I think Lipowitz and Johannessen will finish higher in the GC at the Tour than Evenepoel? Probably not.

In stage 4 of the Dauphiné, Pogačar lost nearly 30 seconds to Vingegaard in a 17.4 km time trial. The flat TT on stage 5 of the Tour de France is 33 km. Does that mean Pogačar could lose nearly a minute to Vingegaard in the TT? I doubt it.

But I believe the most revealing moment of this Dauphiné was Pogačar’s 12 km attack on Valmeinier 1800. When the world champion was riding at nearly 7w/kg, Vingegaard was keeping the gap to Pogačar at 10-20 seconds. After a few more weeks of rest and altitude training, Vingegaard could be even stronger by the start of the Tour de France.

Power Analysis data courtesy of Strava

Strava sauce extension

Riders: