An inside look at Hubert 'Oppy' Opperman, Australia's first cycling star

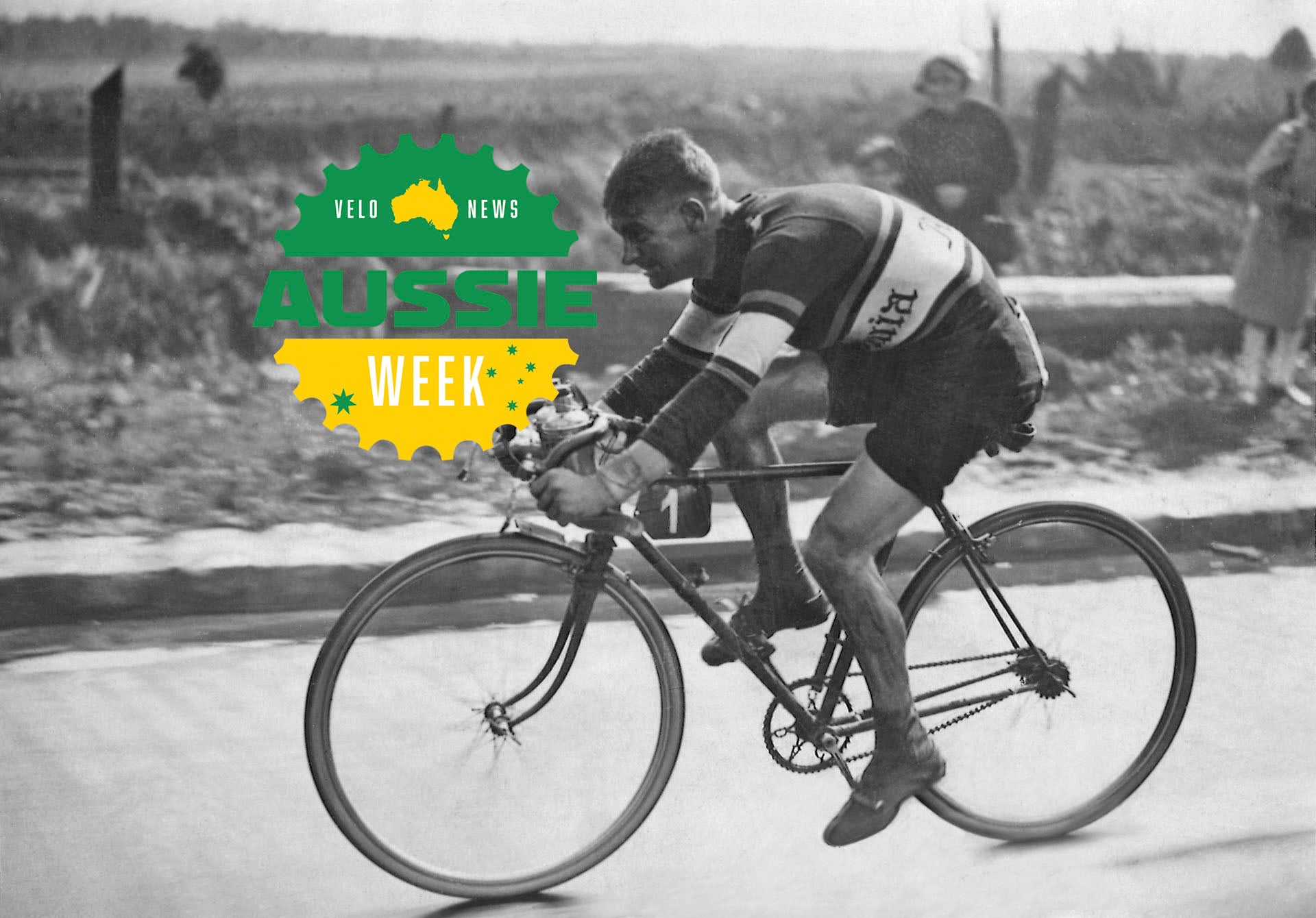

Oppy winning the 1931 Paris-Brest-Paris in record time. Photo: Courtesy Herald and Weekly Times

In a nod to the cancelation of the Australian international cycling calendar, we are turning our gaze Down Under for a week of feature stories, interviews, historical analysis, and other content to celebrate Australian cycling as part of Aussie Week.

Australia has produced more than its fair share of cycling legends. But few come close to the man known as “Oppy.”

Born in country Victoria, Hubert Opperman was the first Australian cyclist to make an impression in Europe. In 1928, he captured international attention as captain of the first English-speaking team to contest the Tour de France. Two decades of racing and record-setting later, Oppy was an icon of the sport and his country. A symbol of national defiance, he carried the hopes of a nation as it weathered the great depression of the 1930s and prepared for battle in the Second World War.

A short, lightly-built man with wing nut-like ears and an easy grin, he was hardly an imposing figure. But what set Oppy apart from his generation could not be seen. The will to win is common to all athletes. But Oppy rode with a determination so furious, blinding, and irrepressible that it left competitors and fans awestruck. He takes his place in the pantheon of Australian cycling heroes.

For those who remember him, he remains a colossal and inspirational figure of Australian sport.

Hubert Opperman Vital Statistics:

Born: 1904, Rochester, Victoria, Australia.

Died: 1996, Melbourne, Australia.

Height: 5 feet 7 inches (170 cm)

Race weight: 143 pounds (65 kgs)

Sponsor: Malvern Star

Nicknames: Oppy; The Little Australian; The Little Gent; The Human Motor; The Flying Machine.

Specialties: Climbing, motor-pacing, time trialing, ultra-endurance.

Style: Consistency and a punishing training regime were key to Oppy’s success. He was also a meticulous planner and strategist who left nothing to chance.

Strengths:

Implacable willpower. Grinding days and sleepless nights in the saddle were bread and butter to Oppy. Today’s athletes have posters of their heroes hanging on their walls. Oppy carried with him an article by an unknown writer, simply titled ‘Learn to Suffer’. He was that kind of guy.

Charismatic and articulate, Oppy was a public relations dream. His promoter, Bruce Small, knew that getting Oppy to write and speak about his rides would sell bikes by the millions. The exposure turned Oppy into a full-fledged celebrity. Small made sure to get Oppy on the radio when he passed through remote towns during his record-breaking rides across Australia.

Weaknesses:

Descending. Oppy could climb with the best in the world. But nervousness and poor bike handling skills dashed any chance of winning a stage in the Tour de France.

Sprinting. A diminutive rider with limitless stamina, he lacked the explosive power of larger men. He compensated by avoiding sprints altogether, by making sure he dropped his rivals early.

International star:

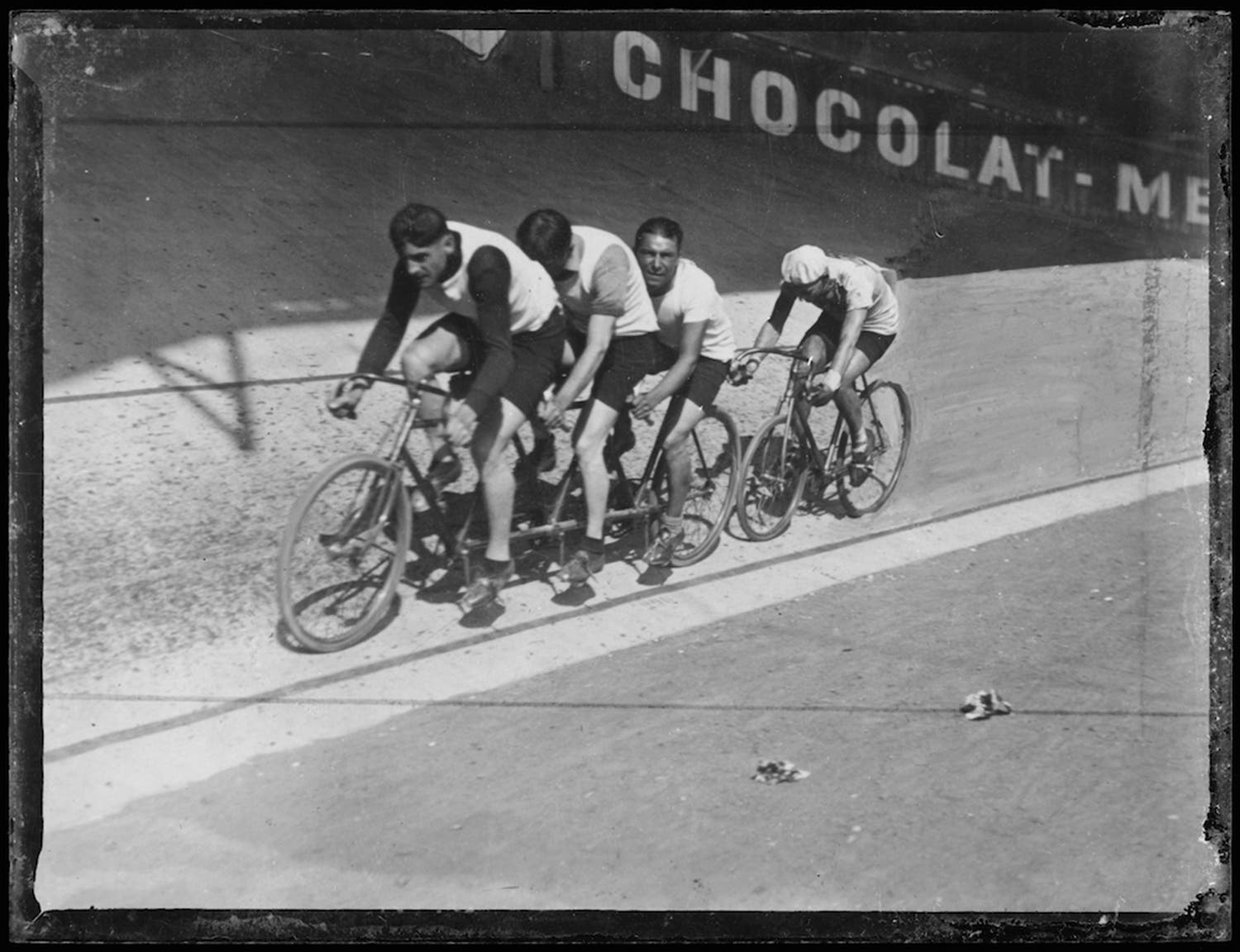

By the time he was in his early 20s, Oppy was a national cycling champion and household name. But it was his success in France that made him an international superstar. He rode with determination in the 1928 Tour, finishing the grueling contest in 18th place. A few months later, he won the Bol d’Or (Golden Bowl), a track event where riders were paced by tandems and triplets for 24 hours non-stop. At the conclusion of the race, he rode on alone for an extra 79 minutes to beat the world record for cycling 1,000 kilometers.

Readers of the sports paper L’Auto voted him the most meritorious cycling champion in Europe. The paper enthused: ‘Hubert Opperman, the sublime son of Australia, is one who should be considered as the symbol of all that is best in cycling virtues.’ He was so moved by the reception he had received from the French people that he started wearing berets; for the rest of his life he was rarely seen without one.

In 1931 Oppy raced in the Tour de France as a member of a combined Australian-Swiss team. In another dogged performance, he overcame dysentery and crashes to finish 12th overall. The founder of the Tour, Henri Desgrange, likened Oppy to a kangaroo, ‘The only animal which does not get its tail between its legs.’

Greatest victory:

In 1931, Oppy became the world’s greatest endurance cyclist when he won the non-stop Paris-Brest-Paris race (772 miles/1,162 kilometers), breaking all previous records, in a time of 49 hours and 23 minutes.

Greatest record:

Oppy spent most of the 1930 setting distance records riding between Australian cities. His overland records culminated in 1937 with his ride of more than 2,700 miles (4,300 km) across Australia from Fremantle to Sydney. This took him just 13 days and 10 hours to complete. The ride was a choreographed as a Broadway show, but the spectacle gripped the nation.

Oppy also held several British cycling titles, including the coveted Land’s End to John O’Groats record (1934).

Secret Weapons:

Oppy learned the delicate art of urinating while remaining in the saddle on the back streets of Paris. He first employed the time-saving technique during the 1928 Bol d’Or when he relieved himself while riding ahead of his rivals who had sabotaged his spare bicycles.

Oppy’s best asset was his devoted wife, Mavys. She served as an unofficial soigneur, sports psychologist, and nutritionist. Oppy never took her for granted, saying that he would have been as powerless as a chain-less bicycle without her.

Performance enhancement:

Abstemious (he neither drank nor smoked), disciplined, and unpretentious, Oppy was seen as a paragon of athletic virtue. His sports beverage of choice was coffee and the South American herbal brew called Yerba maté, which had the same stimulating effect as tea and chocolate.

Oppy’s rivals spread rumors that he slept in the team caravan as it rumbled across the country during his inter-city time trials. This risky and improbable scenario said more about the commercial dominance of Oppy’s sponsor, Malvern Star, than it did about his desire to cheat.

Most unusual achievement:

Oppy also mastered the dangerous sport of motor-pacing, in which a cyclist rode around a velodrome in the slipstream of a powerful motorcycle. In 1930, at the Melbourne Motordrome, he broke the world record for riding one 100 miles (161 km), covering the distance in 100 minutes. Two years later he set another motor-pacing world record by riding 1,000 miles (1,609 km) in just under 29 hours.

Post-cycling life:

Retirement from competitive cycling brought boredom and depression. Oppy was not a man to be brought low for long. In 1949, he was elected to Australia’s Federal Parliament. He held office for 17 years, with an influential period as Minister for Immigration. He then became Australia’s first High Commission to Malta.

Legacy:

Australians have largely forgotten Oppy. His sometimes-controversial political career probably cost him some of his fan base. But his legacy remains profound. Every Australian cyclist from the last century owes a debt of gratitude to Oppy. Above all others, he lit the fuse under Australian cycling which hasn’t looked back since.

In 1985 he was admitted to the Australian Sporting Hall of Fame; his status was later raised to ‘Legend of Australian Sport.’ The Sir Hubert Opperman Trophy, colloquially known as the ‘Oppy Medal,’ has been awarded annually to the country’s best all-around cyclist since the 1950s.

Oppy stopped riding when he turned 90 years old, following an altercation with a bus on Melbourne’s busy roads. He refused to give up the pedals altogether. In 1996, a month short of his 92nd birthday, his wife Mavys found him slumped over the handlebars of his stationary exercise bike. His great heart that had powered him to glory the world over had finally worn out.

Daniel Oakman is the author of Oppy: The Life of Sir Hubert Opperman (Melbourne Books, 2018) and Wild Ride: Epic Cycling Journeys Through the Heart of Australia (Melbourne Books, 2020).