Bahati Foundation highlights Black Cycling History stories all month

Kittie Knox (Photo: Transportation History)

Iman Bahati, director of communication for the 10-year-old Bahati Foundation, is rolling out stories on social media throughout Black History Month that center on cycling. Finding those stories, she found, was a challenge in itself.

Related: The Kittie Knox Award for DEI in cycling

“With Black History Month being here, I though it would be impactful to highlight Black Americans or even British people who have contributed to the sport of cycling,” she said. “It was like finding a needle in a haystack. If you were to Google how to celebrate Black History Month now, you’d get millions of results. But in that list of results, none of them talk about cycling. In newer results you will get Justin [Williams], Ayesha [McGowan], etc, because they are in the news right now. And obviously you can find information on Major Taylor.”

Bahati said the challenge of researching Black history in cycling stems from the lack of historical material surrounding Black riders from that era.

Bahati Foundation founder and former pro cyclist Rahsaan Bahati is Iman’s brother. The missing information, Rahsaan Bahati said, is due largely to oppression.

“Part of why you are not going to find a lot of things from the 1800s to before Major Taylor is because, as you know, Black people were oppressed. A lot of things we take for granted today were not possible then,” he said. “For instance, the gentleman who created the tricycle in the 1800s — and then a tricycle with pedals — that was a Black man, Matthew Cherry. But back then it was hard to get recognition, or even a patent.”

“A lot of Black people got ripped off. Why would that be archived anywhere? No one wants to record that,” he said.

Black cycling stories on the record

Iman Bahati did find a number of stories that she is sharing on the Bahati Foundation Instagram page all this month.

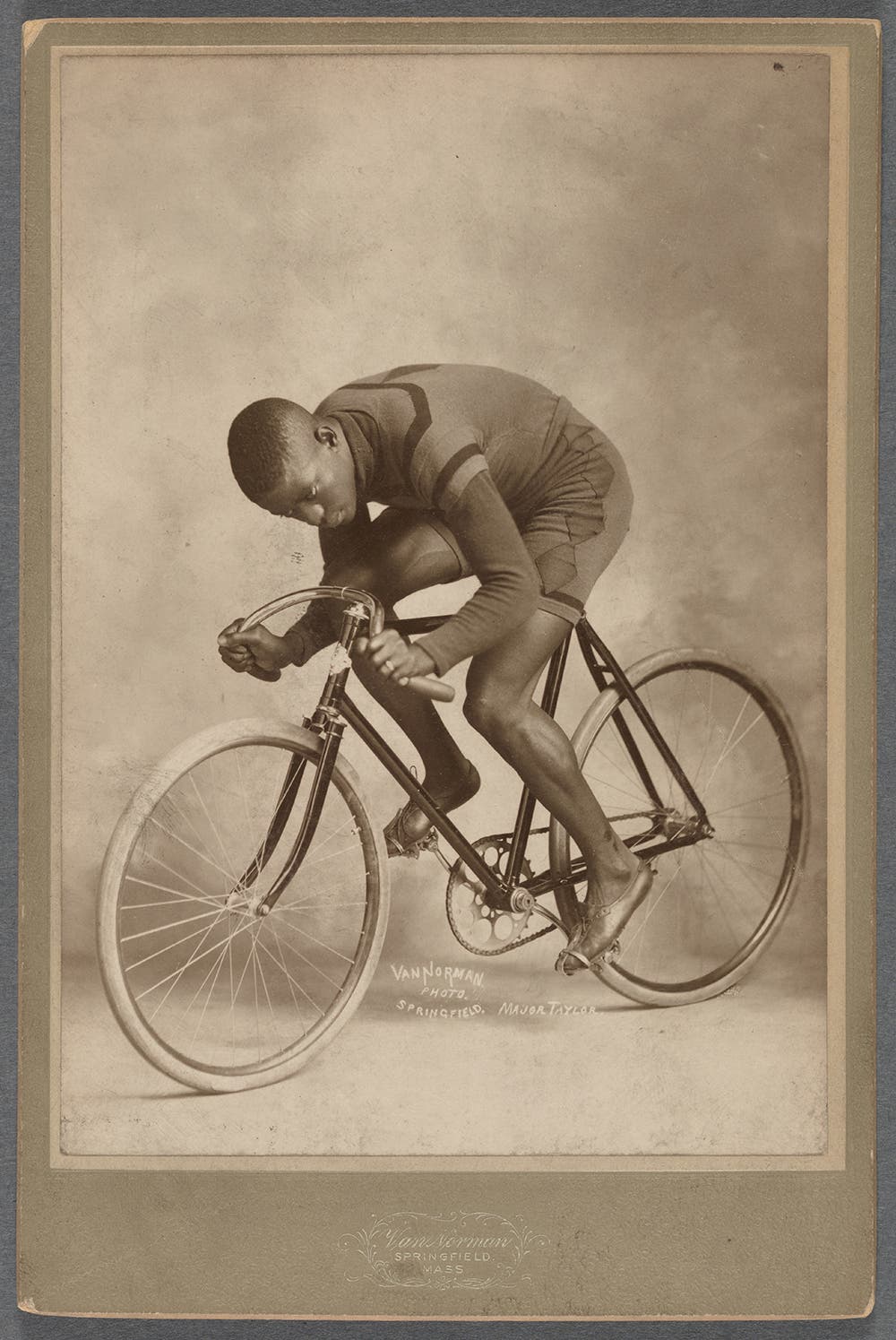

Major Taylor, the 1899 world champion, is of course one of them.

Rahsaan Bahati recommends that all cyclists read Taylor’s autobiography, “The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World.”

“There are a lot of little nuggets,” to pick up, he said. “Like that Major Taylor did not invent but tweaked some things, like the dropped handlebars. They weren’t really running drop bars until he took the bar and curved it to get more aero and aggressive. And of course that is standard on every road bike now.”

The first story that Iman Bahati highlighted was five women riding from New York City to Washington, D.C. (some 250 miles) over Easter weekend in 1928 to make the point that cycling was not a male-only activity.

The Bahati Foundation is also highlighting more recent stories, such as that of Yohann Gène, the first Black rider of Afro-Caribbean descent to race the Tour de France — in 2011. That was a mere 10 years ago, the Bahati Foundation notes.

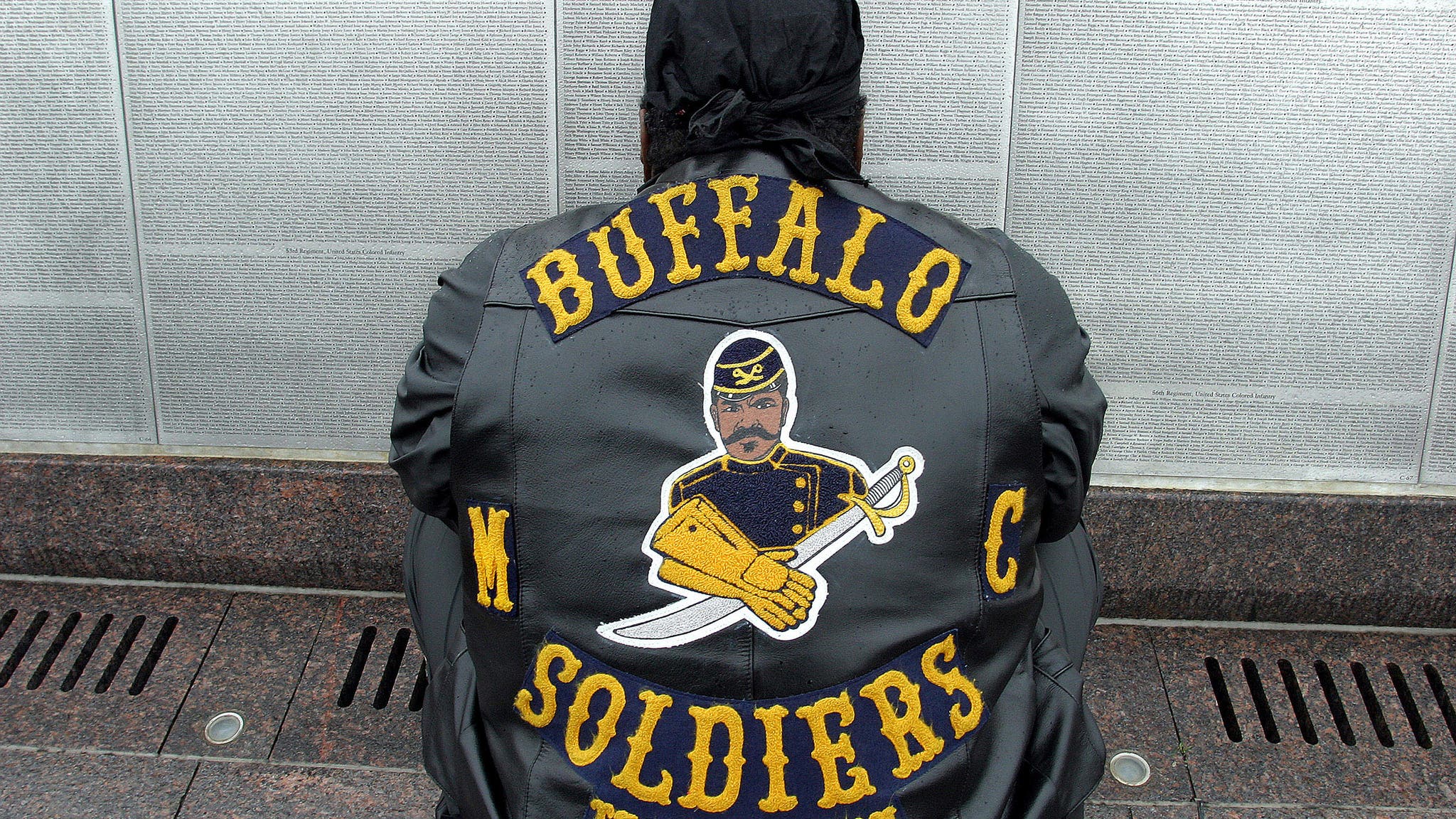

And later this month the story of the Buffalo Soldiers will be recognized.

“Everyone knows the Bob Marley song, right?” Iman Bahati said.

In 1897, Black soldiers in the 25th Infantry were assigned a 1,900-mile trek on bikes, from Montana to Missouri. The so-called Buffalo Soldiers outfit faced blizzards across the Rockies and searing heat in Nebraska, among other obstacles.

“Their journey was difficult,” Iman Bahati said. “The faced a lot of rain. They had no support. They had to meet this deadline, so they averaged 56 miles a day, over 34 days.”

For more stories from Bahati Foundation’s Black History Cycling Month, follow the non-profit on Instagram.