Of the countless bicycle racers who have thrown a leg over their frame’s top tube, Marshall “Major” Taylor’s name has prevailed. He competed as the rare Black professional cyclist at a time when Jim Crow segregation created American apartheid.

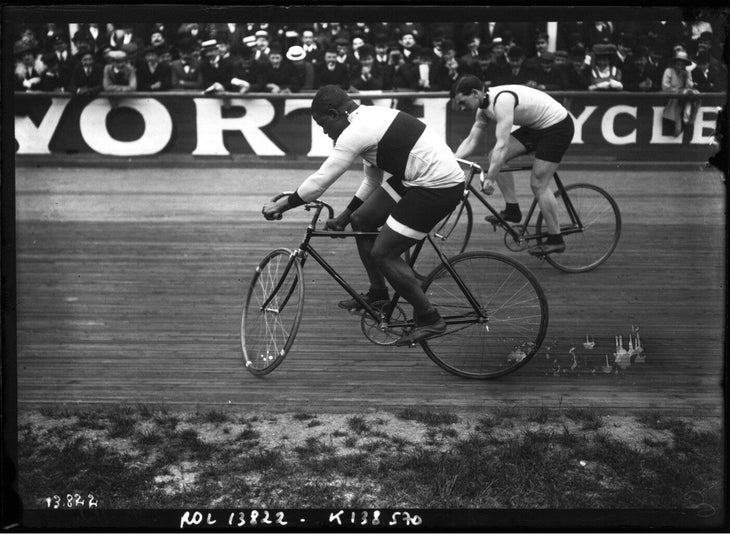

In high-stakes track events against white rivals in front of overwhelmingly white audiences as passionate as NASCAR fans, Taylor showed unearthly leg speed matched with tactical smarts. He won the 1899 one-mile world professional sprint championship in Montreal at age 20 — in front of 18,000 spectators, news hounds, and illustrators from both sides of the Atlantic packing the grandstand and standing 25 deep around the board track. He became the fastest bicycle rider in the world.

Taylor doubled his prize money on that August afternoon by scoring a second gold medal, in the two-mile title. What distinguished him against opponents was his sharp acceleration. He spun his legs faster while seated on his leather saddle, shoulders steady, hands gripping steel handlebar drops, and surged ahead of rivals — a sight as dazzling to witness as hearing a star opera tenor singing solo on stage.

Taylor went on to claim three national crowns, entrance audiences, and captivate the press in A-list cities across three continents for a decade. He set — and sometimes reset — coveted world records galore. After his retirement in 1910, age 31, his adversaries were forgotten like the names of vice presidents. There were just other track sprinters.

In 1989, with Greg LeMond winning the Tour de France and Andy Hampsten conquering Italy’s Giro d’Italia, enthusiasm for American cycling led to three movie productions in the works based on Taylor’s life. A Hollywood studio signed Malcolm-Jamal Warner to portray him. Actress Whoopi Goldberg put up money for a film option on the first Taylor biography.

That year Taylor was inducted posthumously into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame in Somerville, New Jersey (now in Davis, California). His daughter and only child, Sydney Taylor Brown, 85, represented him. A retired Veterans Administration psychiatric social worker, she relished meeting people eager to learn about her father. She looked smart in a tweed jacket, neatly coiffed salt-and-pepper hair, and strode through a crowded reception room with the grace of the former high school varsity basketball player she was. The scent of Channel No. 5 trailed in her wake.

We had dinner together and she expressed the polite indifference of a casino croupier about the prospects of the pending film projects. She said that since the 1940s she had received dozens of movie scripts. They stacked knee-high in her garage. It turned out that the latest prospects vanished like rain puddles in the summer sun.

In 1992, “Tracks of Glory,” a four-hour TV miniseries from Barron Films Production, dealt with Taylor’s two racing seasons in Australia: 1902-03 and 1903-04, his peak years. The script was based on the book, Major Taylor Down Under, by American expat Jim Fitzpatrick, who was a Ph.D. candidate when he accidentally discovered Taylor’s Australian campaigns.

Growing up in America, Fitzpatrick knew of Black athletes like Jesse Owens in track, Jack Johnson and Joe Louis in boxing, and Jackie Robinson in baseball. “I never heard of Taylor, who preceded them all,” he told me on his stateside book tour. The miniseries aired on more than 100 TV stations.

During the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, TV producer Kent Gordis interviewed Taylor’s daughter at her home in Pittsburgh, and grandson Dallas C. Brown, a retired Army brigadier general in Charleston, West Virginia, on camera for a seven-minute film. African-American sportscaster Greg Gumble narrated Gordis’s report between NBC network broadcasts of Olympic cycling events.

The Fluttering Ghost of ‘Breaking Away’

Taylor now, at last, is the subject of a new film, a one-hour PBS documentary titled “Major Taylor: Champion of the Race.” It covers his life, from his birth in 1878 in Indianapolis, through his cycling career, retirement, and death from a heart attack at age 53 in 1932 in the Chicago charity ward of Cook County Hospital.

The documentary is set to air in May on 350 PBS stations nationwide; stations set their own broadcast schedules. PBS’s website claims its network reaches nearly 100 million people each month through television, another 28 million people online, and millions more on the PBS App.

Behind the documentary is Todd Gould, senior producer/director at WTIU, a PBS member in Bloomington, Indiana. The ghost of the 1979 movie “Breaking Away” flutters in Bloomington. The sunny coming-of-age comedy-drama with a quirky bicycle racer protagonist was filmed there. Bloomington, an hour’s drive south of Indianapolis, is home to Indiana University. Its annual Little 500 spring classic race sees relay teams of four riders take turns pedaling single-speed bikes around the campus’s quarter-mile running track, the setting for the movie’s climax. IU alumnus Steve Tesich won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

Gould’s turning the idea of a Taylor documentary into a finished product reaching millions, after dozens of efforts failed over the decades, could be compared to the British legend of Arthur pulling the sword from a churchyard stone.

Gould has beavered away on producing historic features for PBS, ESPN, A&E, the BBC, and The Learning Channel. He has lived most of his 58 years in Indiana. He stands five-foot-six and has the build of a lithesome marathon runner. His mat of hair is trending gray. He speaks with assured enthusiasm. He studied at Indiana University, majoring in communications with a minor in business marketing.

As a student, he began working on local programs for WTIU, a nonprofit owned by Indiana University serving some 600,000 households. “I started to gain experience with funding and distribution of projects,” he said in a phone interview.

After graduation in 1988, Gould joined the PBS affiliate WFYI-TV Indianapolis. He wrote articles for regional and national magazines and produced documentaries on once-renowned luminaries passed-by over time with Indiana ties and national magnitude. An early project he researched, wrote, directed, and produced became “Pioneers of the Hardwood,” about the Hoosier state’s place in the formation of professional basketball. It aired in 1993 for the Indiana Public Broadcasting System.

His inspiration grew from the sport’s hold on him and advice from his paternal grandfather, Homer “Hurley” Gould, captain the McKendree University basketball team and a member of the school’s athletic hall of fame. Todd Gould admired the men featured in his documentary so much that after he wrapped up the documentary, he spent years working on his own time, on evenings and weekends, to research deeper and write Pioneers of the Hardwood: Indiana and the Birth of Professional Basketball (Indiana University Press, 1998).

He saw a future in rescuing forgotten legends. He mined the story of Charlie Wiggins, an African-American racecar driver of the 1920s-30s from Evansville, in southern Indiana. Nicknamed “the negro speed king,” Wiggins was barred from driving in the Indy 500 because of the color of his skin. He helped organize a summer circuit, dubbed the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes, for African-American drivers to race on dusty fairground tracks in Indiana and around the Midwest against a backdrop of Prohibition, mobsters, and the Ku Klux Klan stirring up racial tensions.

Gould produced the PBS documentary, “For Gold and Glory,” and published a book, Gold & Glory: Charlie Wiggins and the African-American Racing Car Circuit (IU Press), both released in 2003.

More than 50 Scripts

Gould returned to WTIU in 2016. He has produced original documentaries that garnered 20 Emmy Awards. They include “Ernie Pyle: Life in the Trenches,” about the former Indiana University student-newspaper editor who became a Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist and was killed in action as a correspondent in World War II. Another, “The Music Makers of Gennett Records,” delved into the family-owned 1920s Gennett recording studio in Richmond, Indiana. Young Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, and Bloomington’s own native songwriter and composer Hoagy Carmichael recorded there before they gained national fame.

As Gould progressed from project to project, he kept coming across information on Major Taylor. “Taylor is part of the state’s history,” he said. “His story extends way beyond Indiana. What I look for in documentaries is a subject that may have roots in Indiana that are universal. He was a trailblazer for African-American athletes and a civil rights icon. He was not just racing bicycles on tracks before audiences filling the grandstands and surrounding cheap seats, but also confronting the issue of race in society.”

In 2021 Kisha Tandy, a curator of social history at the Indiana State Museum, began organizing a special exhibit, “Major Taylor: Fastest Cyclist in the World.” It opened March 5, 2022 in the museum and ran through October 23. Visitors saw enlarged vintage photos of Major Taylor mounted on walls. The Peugeot bicycle that he raced on in Paris was displayed, on loan from the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame, along with a copy of his 1928 self-published autobiography that he signed to W.E.B. Du Bois, a cofounder of the NAACP. On view from the museum’s own collection were trophies Taylor won, scrapbooks he kept, letters and postcards he wrote in neat cursive to his wife, Daisy, and to friends.

“Kisha’s exhibit was gift-wrapped for me,” Gould said. “I had worked in the past with the Indiana State Museum and spent a lot of time with its archives. So I read through Major Taylor’s scrapbooks and journal entries, letters to Daisy when he was competing overseas. Reading his autobiography was a powerful experience, like a first-person interview. I got to hold these documents in my hands to read. That’s an awesome opportunity.”

The exhibit coincided with the five-day International Cycling History Conference in July in Indianapolis for historians. “Major Taylor’s great-granddaughter, Karen Brown-Donovan, came. I told her that I was thinking of doing this documentary. She said she inherited a stack of movie scripts about him from her grandmother, and Karen received even more. I asked her how many there were. She said more than fifty.”

At the conference Gould met Lynne Tolman, founder of the Major Taylor Association, a nonprofit honoring the eponymous Taylor in his adopted hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts. Tolman, a journalist, ran the campaign that funded the $250,000 monument, 10 feet tall with a statute of Taylor, that was unveiled in 2008 outside the Worcester Public Library.

Tolman, Brown-Donovan, and Tandy give on-camera interviews in the documentary. A dozen other men and women, Black and white, offer knowledgeable perspectives of what Taylor meant to the sport, the nation’s Black community, and his struggles with racial prejudice before the Great Migration around 1915 when 6 million Southern Black residents moved to the North.

Sports journalist and journalism professor Kevin Blackistone points out that Major League Baseball experienced social troubles, but those players were also on teams. “Major Taylor was alone. It was Major Taylor versus everybody else, and everybody else was white.” Blackistone notes that Taylor sought to show what a Black person could do when given an equal chance in competition.

Former 400-meter track hurdler extraordinaire Edwin Moses gives a perfect-pitch gravitas interview. Like Taylor, Moses is a two-time a world champion and set world records — four times — in his event. Moses, an Olympic gold medalist in 1976 and 1984, drew worldwide attention for his decade-long winning streak, from 1977 to 1987; he won 122 consecutive international races. He puts Taylor at the performance level of world heavyweight boxing champions Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali.

“I can’t imagine how Major Taylor dealt with it,” he said, “with the extreme-in-your-face racism of the Jim Crow era.”

Major Taylor’s Furrowed Brow

Gould had planned to hire actors to narrate. Then came the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists strike over a labor dispute with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television. “There was no telling when the actors would become available,” he said. “I decided to try musicians. Like actors, they’re comfortable in front of the microphone or camera.”

Branford Marsalis, familiar to viewers as a jazz saxophonist, composer, and bandleader, reads letters Taylor wrote to his wife, quotes what journalists wrote about Taylor, and gives voice to first-person excerpts from his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success against Great Odds.

“Branford Marsalis speaks the words that Major Taylor actually wrote,” Gould said. “It’s like we’re listening to Taylor himself.”

Mezzo-soprano opera singer Marietta Simpson, the Distinguished Rudy Professor of Music at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, narrates the documentary and provides commentary.

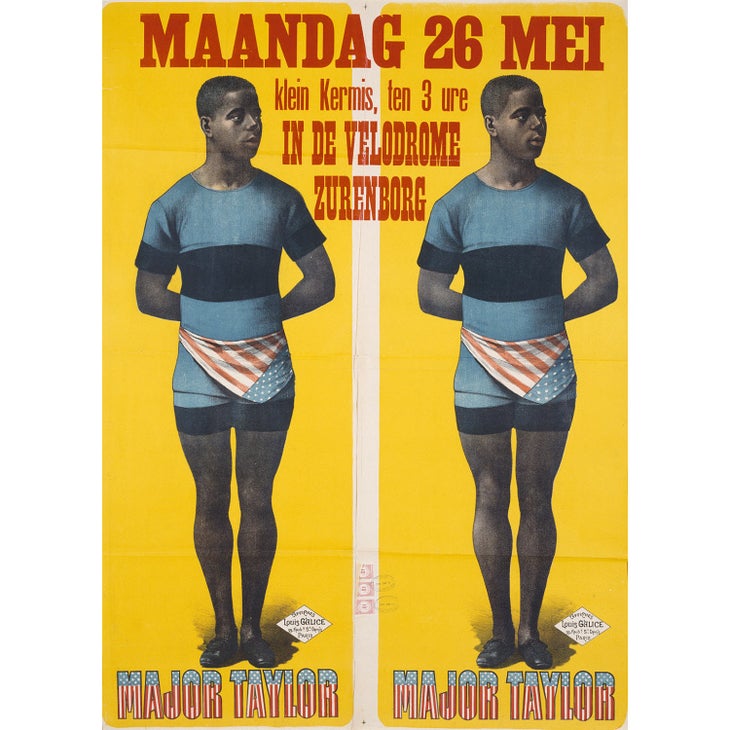

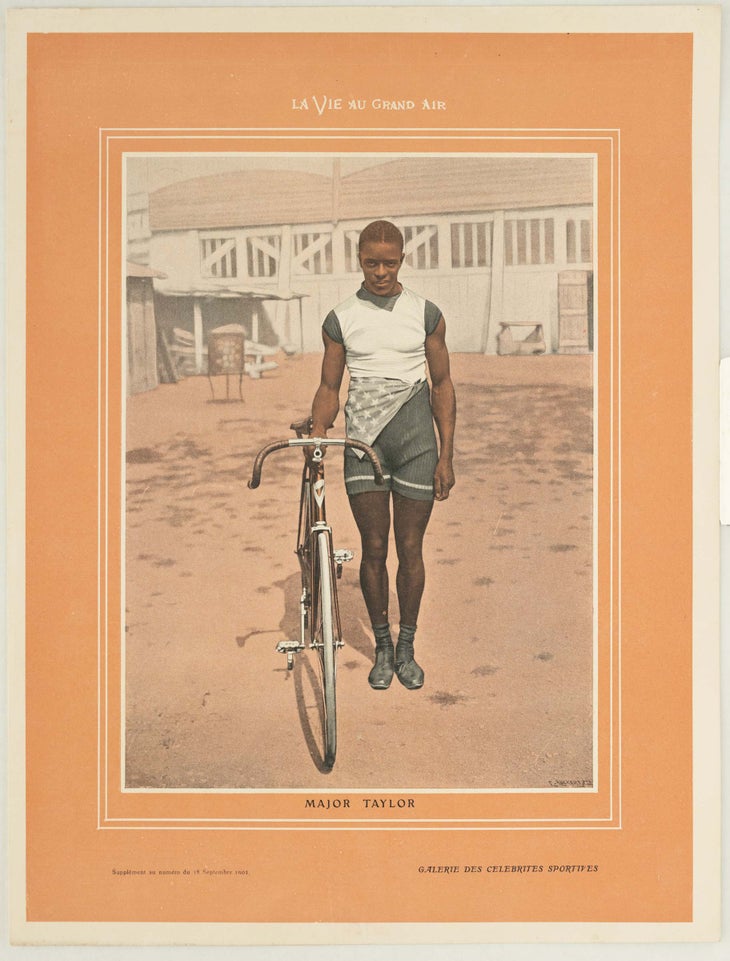

Gould deploys many newspaper and magazine articles chronicling Taylor. Paris journals often splashed Taylor’s face on the cover — star treatment he didn’t get in his homeland. The battery of racing photos on tracks in front of packed galleries around Europe and Australia seem fresh. Taylor is also shown mingling on social occasions with other headliners dressed like bankers. The cumulative effect comes across as a powerful testimony of the man and his time.

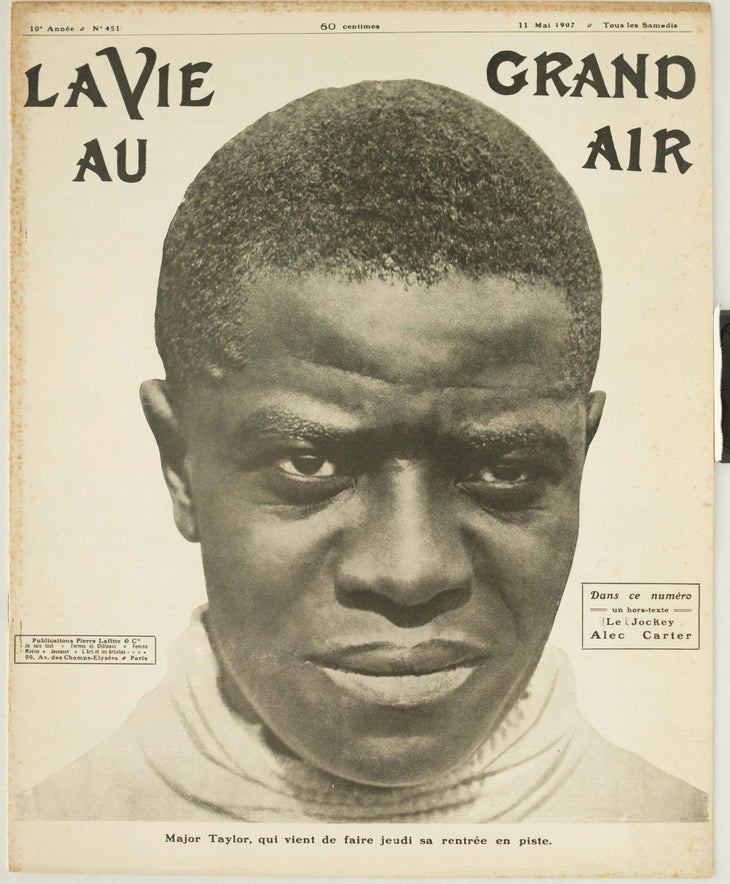

During his racing career, Taylor aged prematurely, his face reflecting psychological strain. By 1907 on a campaign in Paris, his face on the cover La Vie Au Grand Air shows the eyes of a combat veteran. Smiles that came naturally in his youth had disappeared.

“You can see how he hardened himself,” Gould said. “Year after year, his furrowed brow grew deeper.”

I thought that missing from the camera was a contemporary Black rider weighing in as a through-line. Like former national professional sprint champion and Olympic silver medalist Nelson Vails, or two-time national amateur sprint champion Scott Berryman, or the track rider, historian, and internationally acclaimed blues guitarist Otis Taylor (no relation to Major Taylor).

The documentary took about four years to make, Gould said. “My hope is that the national audience will learn about Major Taylor, what the country was like when he was young and competing, and leave people wanting to learn more. I think his story is so strong that there can be 10 documentaries on Major Taylor. He was facing great hostilities and harsh push-back from a white society that might not be accustomed to seeing a Black face.”

“Major Taylor: Champion of the Race” comes nearly a century after Taylor’s death. Finally, he has a documentary that does him justice. Like the lyrics of Sam Cooke, It’s been a long time/A long time coming.