New Book Surveys Black Cyclists from Major Taylor’s Era to Today

Black cyclists have always defied the odds in the overwhelmingly white sport and pastime, Lees-McRae College history professor and retired amateur competitor Robert J. Turpin observes in Black Cyclists: The Race for Inclusion, his unprecedented epic narrative of Black American cyclists. Turpin pored over bygone publications covering the sport and industry, like an archeologist brandishing a paint brush to free bones sandblasted in the past, before he progressed to interview contemporaries.

Anyone riding prototype high-wheel bicycles in the 1880s personified economic means along with athleticism and physical and social mobility. Turpin cites David Drummond, a Black carpenter, renowned in Boston for his riding skill and physical stamina. In November 1885, The Bicycling World listed Drummond joining nine white riders pacing Louis “Birdie” Munger in setting a new 24-hour national distance record. Munger, a white professional rider, later trained young Marshall “Major” Taylor to become world champion.

The 1890s saw the introduction of lighter modern bicycles, featuring both wheels the same size on a diamond frame equipped with pneumatic tires that replaced solid rubber tires. But Drummond and other Black riders encountered resistance to their participation. Some event organizers rejected entries from Black cyclists. Cycling’s popularity ballooned from coast to coast. Spectators flocked to watch track events. In 1894 the League of American Wheelmen (predecessor to the League of American Bicyclists and USA Cycling) sanctioning the sport — and lobbying for better roads — barred Black people from joining the organization and from competing.

Major Taylor from Indianapolis rode as the rare exception because of his great fast-twitch speed. His victory at age 20 in the professional one-mile event at the 1899 world cycling championships in Montreal against U.S. and foreign champions earned him the title of world’s fastest bicycle rider. His life story and bruising struggles from racism have been the subject of more biographies than any other American rider. Turbin discusses him sufficiently and profiles many other Black cyclists who also raced but have been overlooked.

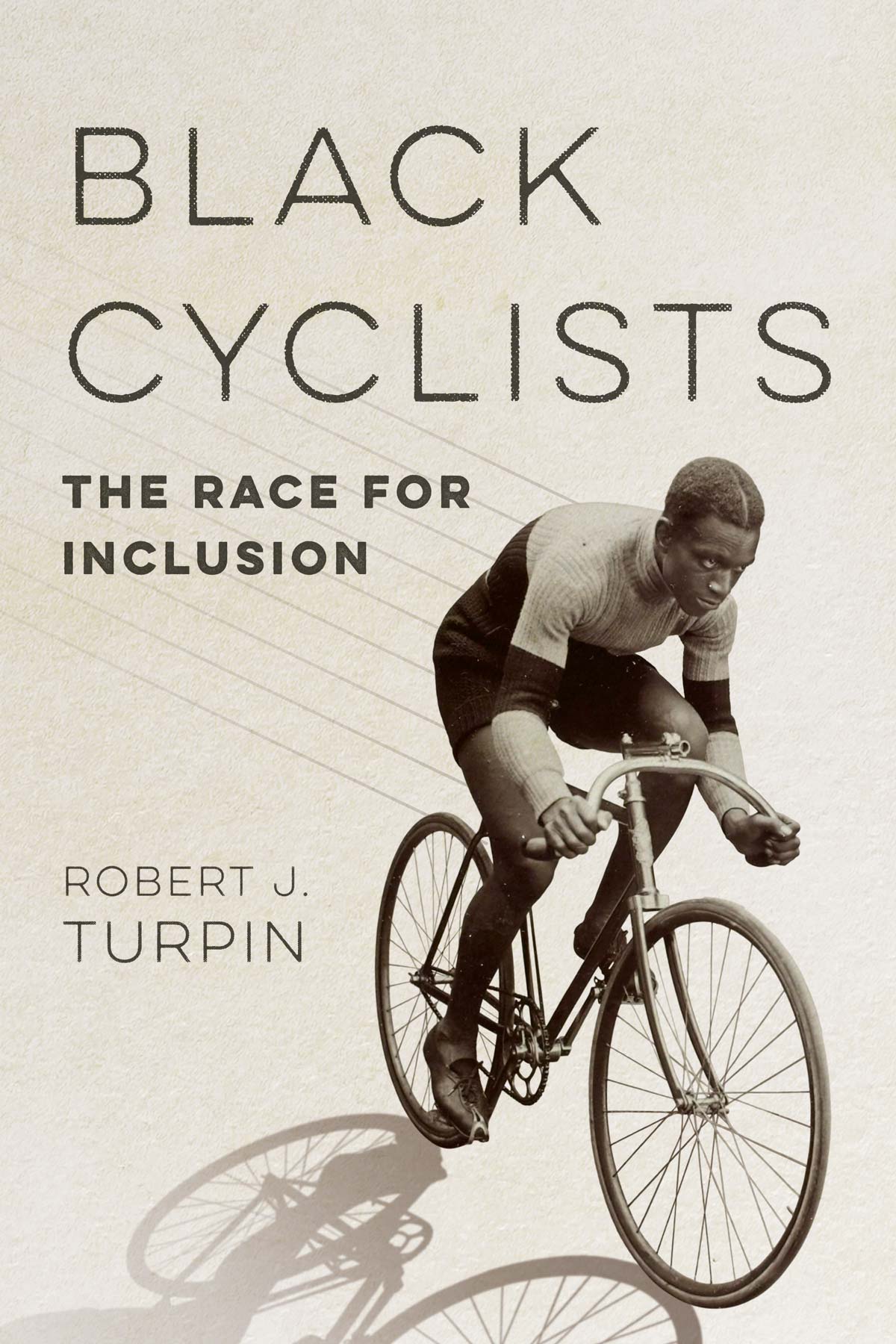

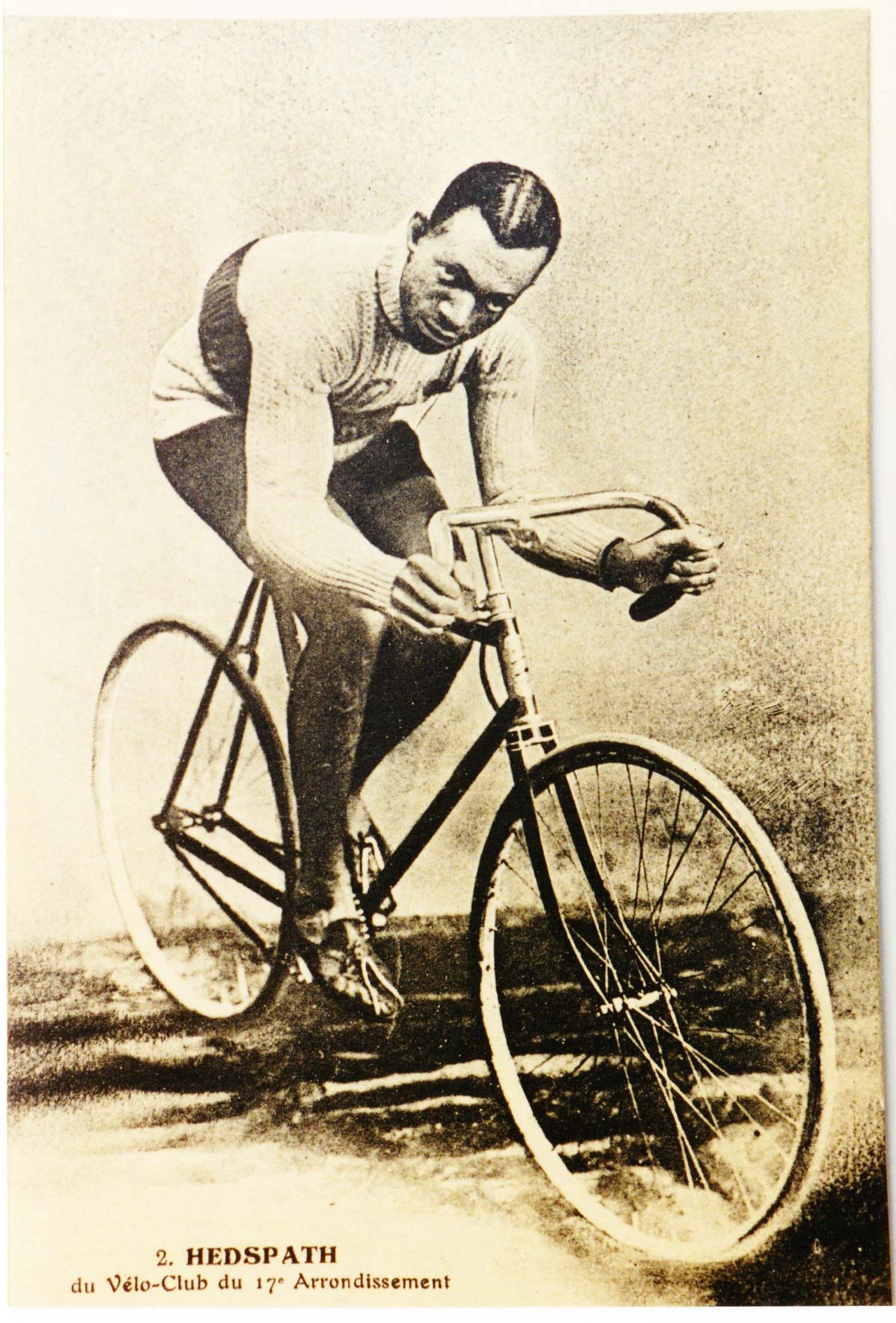

The cover of Black Cyclists features Taylor’s fellow professional, Woody Hedspath, bent low over his track bike, hands gripping the drops, looking straight ahead and ready to dash off the page. The image is credited to Paris photojournalist Jules Beau, circa 1904.

In the spring of 1903 in Paris, Hedspath and Taylor teamed up in track events that drew big paying crowds. The pair matched pedal strokes and tactics against French rivals in contests promoted as Noir contre Blanche (Black versus white) to the delight of the Paris press corps. Beau and other photographers lugged their tripods and boxy wooden cameras around to take their pictures. Paris sports magazines such as La Vie Au Grand Air splashed their faces across front pages prominently displayed on newsstands and kiosks to promote circulation — unlike American cycling publications that trafficked in minimal, begrudging, condescending coverage.

Turpin’s book is the first to profile Hedspath, a native of Kentucky who called Indianapolis his home. Taylor set national professional records galore; Hedspath became the only other Black rider in their lifetime to also set a national record — one that outlived them both.

Unlike Taylor, who sailed home to America by way of Australia for an endless summer campaign, Hedspath took up residence in the City of Light. He married a French woman, Rosalie LeMaitre, a ballerina, and fathered a daughter, Genevieve. Turpin discusses Hedspath’s career on tracks around France, Germany, and — like Taylor — Australia. After Hedspath retired from racing in 1912, he cashed in on his knowledge and connections to manage headliners, among them Lucien Faucheux, winner of four French amateur and professional sprint titles.

Turpin features William F. Ivy, another Black pro who earned money on Paris tracks and road races during the 1909 season. Ivy rode in the same pack as Tour de France winners Octave Lapize of France and François Faber of Luxembourg as well as French hero Eugène Christophe, the first ever to wear the coveted race leader’s maillot jaune (yellow jersey), introduced a decade later. On the track in a 24-hour contest, Ivy challenged the mustachioed Leon Georget, France’s reigning long-distance rider, nicknamed The Brute. Ivy’s prize money paid for his ticket to sail in style on an ocean liner across the Atlantic to New York.

Ivy also served two enlistments in the U.S. Army, when the ranks were racially segregated (President Harry Truman integrated the armed forces in 1948). Turpin notes that in later years when Ivey lived in Rock Island, Illinois, the experiences he told friends about his cycling exploits seemed to strain belief.

After the 1930s, press coverage of cycling in general and Black cyclists specifically vanished. Turpin’s last chapter, “Epilogue: Born Again,” ranges from the 1950s to 2019. He writes about 16-year-old Perry Metzler, winner of the Amateur Bicycle League of America (another predecessor to USA Cycling) national junior title for boys aged 16 and under. Metzler became the first Black national champion since Major Taylor.

Ken Farnum, a track rider who immigrated to New York City from the Barbados after riding in the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, became a folk hero for the next generation of Black riders. They include New Yorkers Herb Francis, a track sprinter on the 1960 U.S. Olympic Cycling team in Rome, and Oliver “Butch” Martin, who rode in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and 1968 Mexico City Olympics. New Yorker Nelson Vails took home a silver medal from the 1984 LA Olympics.

More Black people have subsequently contributed to the quality of American racing. Californian Rahsaan Bahati won 10 national championships. Justin Williams has won 11 titles. Ayesha McGowan of Atlanta won a national women’s title and turned pro. All of them fought hard battles to earn their way into a white-dominated sport.

Turpin’s footnotes in the back of the book are as captivating as his narrative. I found myself reading the nine chapters and epilogue while flipping to the back to check out more information. He resurrects lost careers and provides the context of their time to better understand American cycling history.

Black Cyclists: The Race for Inclusion

By Robert J. Turpin. 233 pages. Illustrated with photos and art. University of Illinois Press.