VN Archives: Before there was Strade Bianche, there was Tuscany's L'Eroica Gaiole

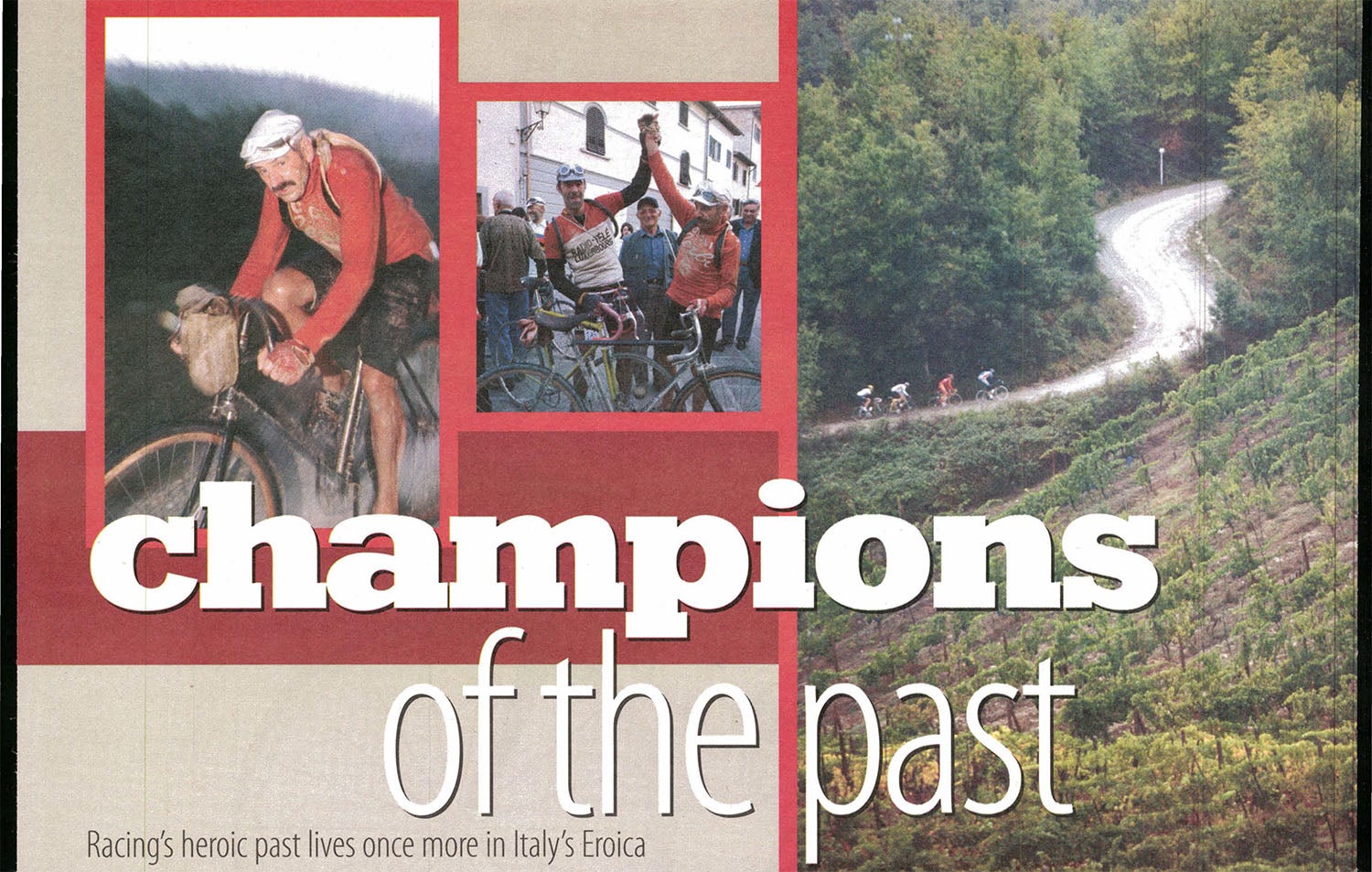

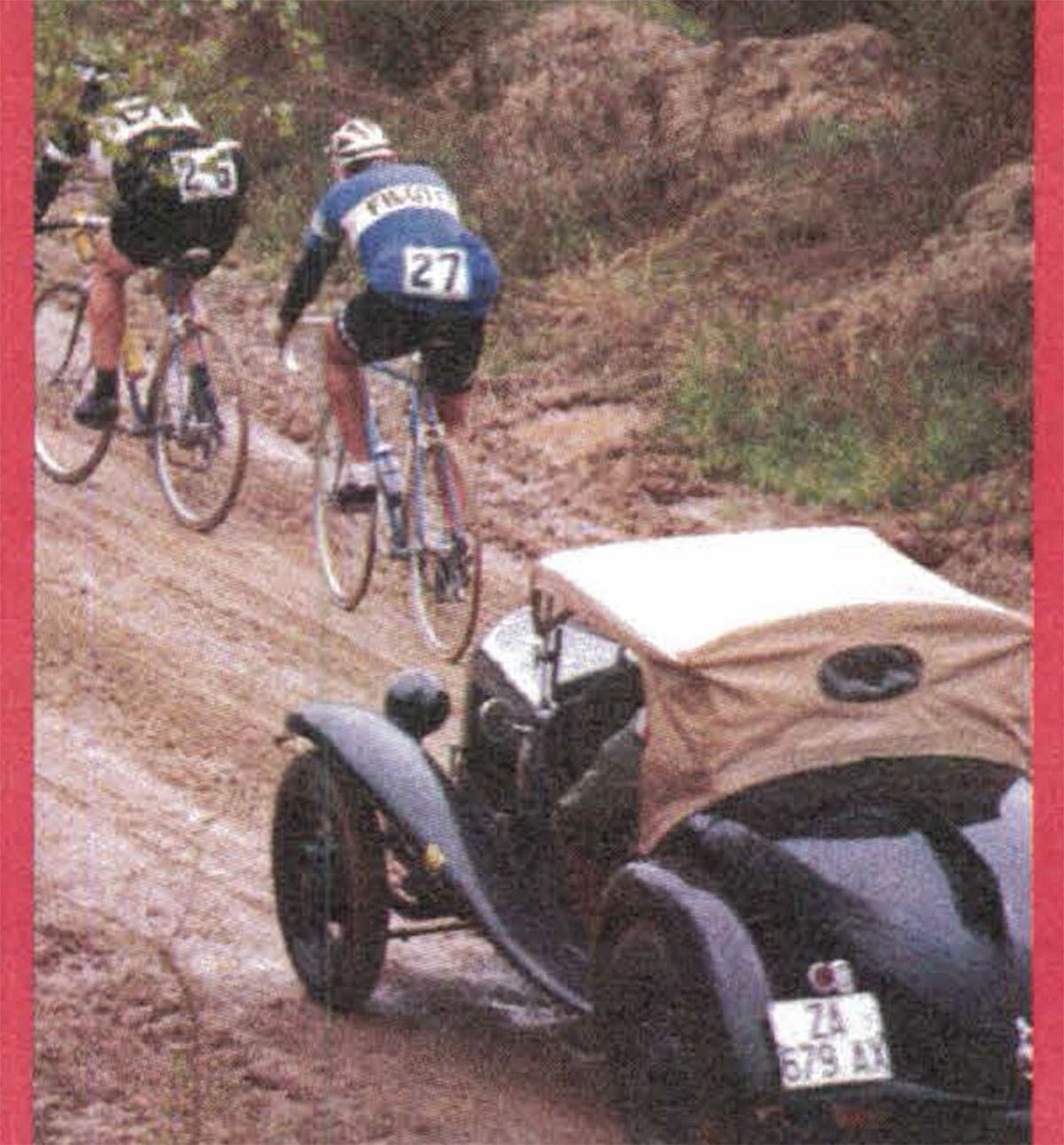

Each September, the heroes of the road gather in the little town of Gaiole for the “L’Eroica.” This old-school race covers 125km of winding gravel and paved roads in one of Italy’s most famous regions, the wine-growing land of Chianti, in the heart of Tuscany. On September 30 last year, a Sunday, the heroes departed Gaiole through sheets of rain and streaked toward the muddy vineyards to prove their worth astride bicycles from another era, costumed in clothing from times past. The greatest of them soon fell behind the leaders during the arduous fourth edition of the Eroica …

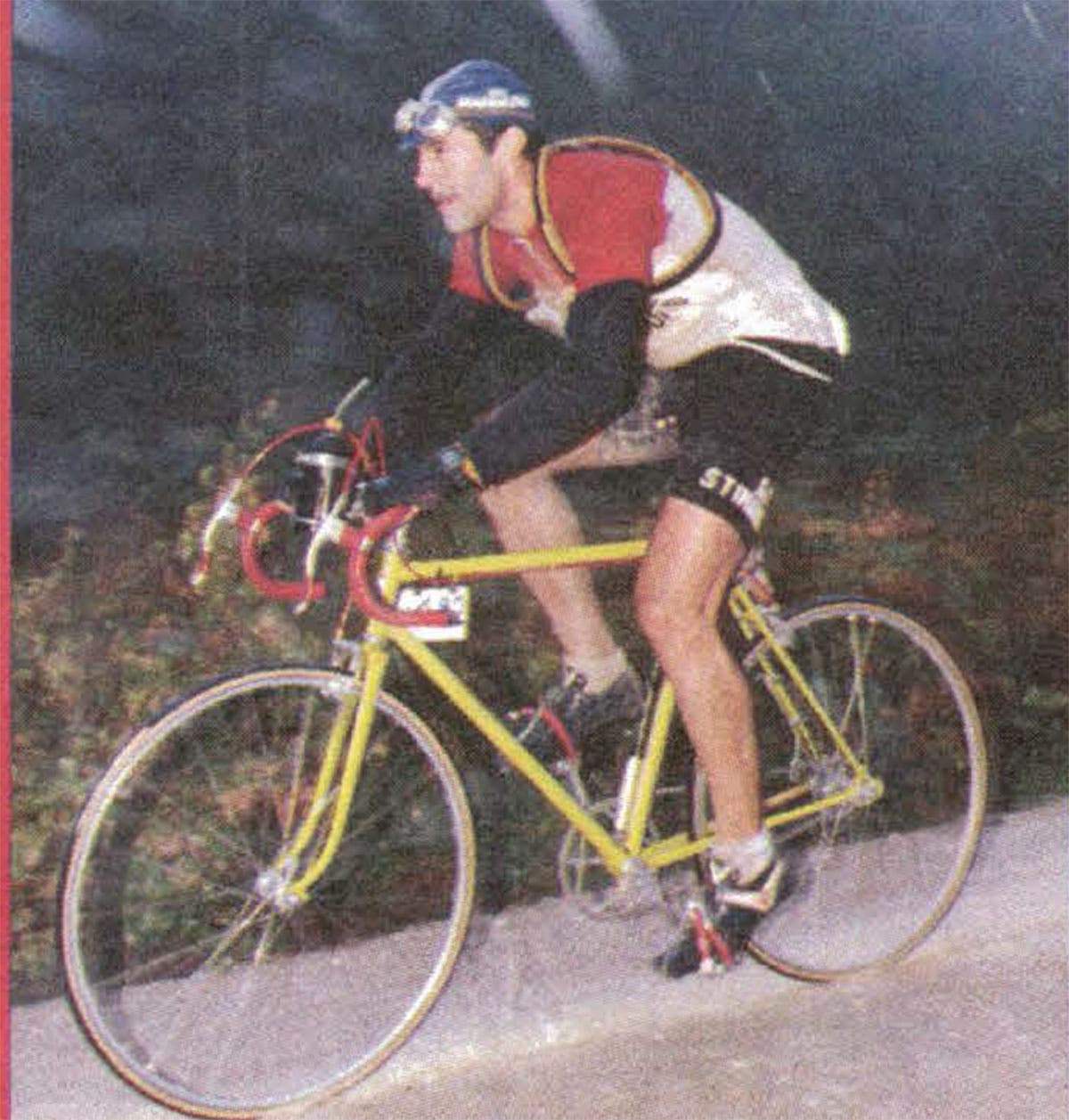

Fifty-five kilometers into the day, Luciano Berruti stood and propelled himself and his 35.2-pound single-speed 190 Peugeot up another climb. The course fell precipitously in switchbacks from the hill town of Radda, then launched riders at the valley’s opposite wall, toward the ancient fortified castle of Volpaia. Berruti led his competition into another of the countless hills on a road of pulverized white stone. His woolen shorts sagged from suspenders, waterlogged from two-and-one-half hours of cascading rain. Foggy, mud-splattered goggles on his helmetless head, and a thickly woven Cicli Gerbi jersey framed the grimace of exhaustion and ferocity on the 58-year-old’s face.

David Maddalena followed, having ceded five seconds at the initiation of the 15-percent grade. Maddalena — an Italian with an anglicized first name — had twisted his shifting rod to find the easier of his two gears, and the maneuver required two hops of his rear wheel to reseat the chain. He glanced down to confirm the change, then raised his face toward the few spectators hardy enough to endure the weather. Ashen and soaked, Maddalena parted his lips in a smile, belying the effort required to keep Berruti in check on the hill.

Nearly a minute later, Luigi Luzzana, 62 years strong, arrived, defiantly churning the pedals of his celeste Bianchi as water channeled down grooves in the broken road. He heaved mightily as he climbed, passing the vineyards of some of the world’s greatest red wines — Pergole Torte, Querciagrande, and the Antinori family’s Chiantis. The bearded Luzzana gave nothing away in his expression, save for the eyes. They followed the curve in the road just ahead that led to Berruti and the finish, more than 70km away.

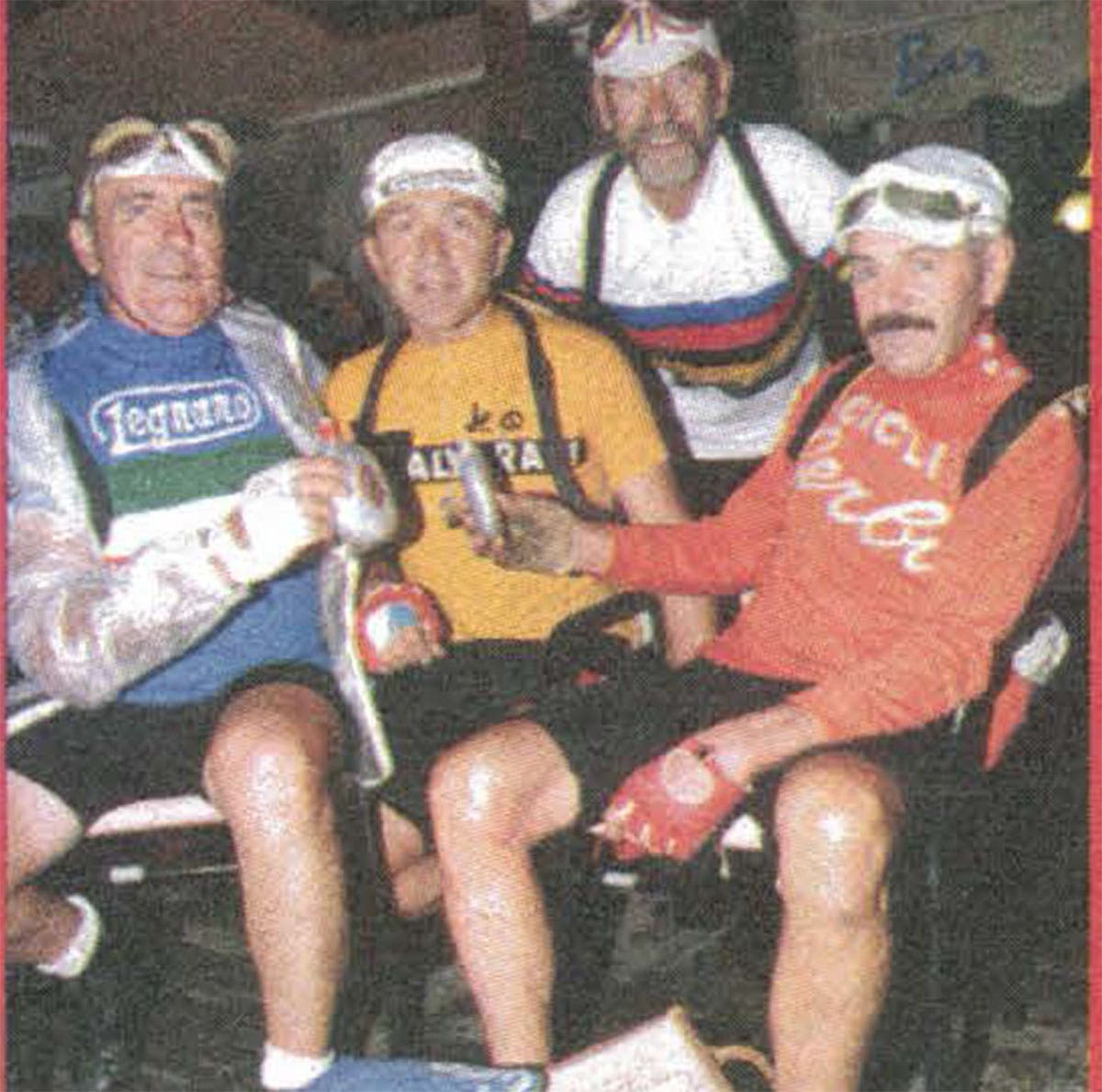

Though the starter’s whistle had unleashed more than 60 riders at the line that morning, the race had truly been reduced to four heroes by this point, and the last of these trailed some minutes behind Luzzana — Ermes Leonardi, another competitor in his 60s. As the three others beg the grade up Volpaia, Leonardi stood on the shoulder of the narrow ribbon of asphalt leading into Radda. He had suffered his fourth flat of the day, and after stripping his last tubular from his shoulders and mounting it, he threw a leg over the top tube and began pursuit. His wool jersey hung heavily on his body. His jersey, printed with the logo of the legendary Legnano team, presented itself in a darker shade of blue, with streaks of road grime running vertically.

The race would last another four hours. Countless young competitors would retire, asking with eyes diverted toward the slick road surface, “What’s the quickest way back to Gaiole?” Their synthetic clothing and modern bicycles, most nearly 20 pounds lighter than Berruti’s Peugeot, were no help in one of the most unique road cycling races in Europe.

A race like no other

The Eroica challenges and honors cycling’s heroes, past and present. At most races, youthful, fit and fast riders command the spotlight; and true, at this year’s Eroica, a young rider arrived first, wearing Lycra shorts, sporting 10 speeds on his rig, and even a fashionable sprout of facial hair. A few spectators offered him polite applause, but the real champions of the day were the men who were hours behind at that point. Men like Luzzana, Berruti, Leonardi, and Maddalena.

There are no hard-and-fast rules for the Eroica. The style with which one competes, the ethos of one’s approach to the bike; these count more at the finish than does time. The race asks only that one pedal in honor of the increasingly scarce spirit that inhabited the hearts of the greats, like Merckx, Van Looy, Binda, and Bottechia. Show up and tide, offer up your sweat on the altar of these gods. Perform your genuflection in wool shorts and jersey, astride a 30-pounds plus bicycle with just a few gears, and chances are your prayers will carry you further, even if your deliverance comes that much more slowly.

The 2001 Eroica was the fourth edition. I arrived in Gaiole the night before the race with Enrico Caracciolo, a journalist and photographer specializing in cycle touring in exotic destinations such as Madagascar, Alaska, Iceland, New Zealand — and the dirt roads in and around Tuscany.

At the local gymnasium in Gaiole was an exhibit to make any cyclophile weep in ecstasy. More than 50 vintage bicycles, including an 1890 Clement with a single gear and wooden wheels (ridden the year prior by Berruti!) led visitors through the evolution of the machine. Antique jerseys and even a few restored Vespas and Lambrettas whetted everyone’s appetite for Sunday’s race.

Don’t think of it as just a bike race, though. The Eroica is the crown jewel in a righteous conservation movement. Due to increasing pressure from automobile-based tourism and modernization, the remaining bianche strade — or white roads — in Chianti are in peril of being paved over, just like the pavé of northern France. Furthermore, desirable cycling destinations like Tuscany, Provence, and even California’s Napa Valley and Sonoma County, run the risk of selling their souls to four-lane highways and motor lodges.

The race’s founder and director, Giancarlo Brocci, a medical doctor by education who has since left the practice to pursue his passion for promoting cycling, is in the process of organizing what he calls the Chianti Cycling Park to help include the bicycle in Chianti’s future, as well as that of Italy and the rest of the world.

The evening before the Eroica, Brocci explained his strategy. “We hope to build a cycling park here in the Chianti, with the help of the Siena tourism office, local businesses, and the towns in the area,” he said. The park would feature itineraries catering to all abilities, from 10-km-a-day tourists, to the seasoned cyclist looking r rides of up to 100 miles in a single outing. Caracciolo has been instrumental in developing many of these routes.

After launching the program in Chianti, Brocci plans to export the model to other cycling areas in Italy, such as Umbria and Piedmont. Indeed, the Eroica may grow over the coming years into a mammoth, 200km-plus course that cycle tourists could ride throughout the year, or in stages. The goal is to make it a yearly classic, with a formidable course and established route to be ridden all year, but raced one day in the fall.

Preserving cycling’s history

The Eroica may be a cornerstone in Brocci ‘s movement to protect and preserve one of the world’s great cycling landscapes. But it also acts as a moving monument to a paradise lost in cycling, that once-upon-a-time world inhabited by an endangered species: the complete rider, impervious to fatigue, immune to pain, unflappable no matter the circumstance, those who’ve passed to the pantheon of gods alongside Kelly, Hinault and Janssen.

“When I’m riding, I don’t feel pain, I only think of pedaling,” Berruti said at the start of this year’s race. During the 2000 edition, when Berruti rode the 1890 Clement, his costume included leather cycling shoes from the period. The cleat and pedal pressure eventually sliced both his feet across the ball, an injury he only discovered at the finish of the race, which counts two-thirds of its course on bianche strade.

Another telling anecdote: The 35-pound Peugeot on which Berruti performed at last year’s Eroica has been to the summit of L’Alpe d’Huez. The bike, a black beast complete with wooden rims, an un-cushioned leather saddle, and one gear — a 44×23 — should be a museum piece, but Berruti finesses it on the descents, wills it up the climbs, drives it along the flat sections.

“On l’Alpe d’Huez, after four kilometers, I thought I wouldn’t be able to ride it, but I rode the whole way without stopping,” he said, smiling. “Some of it even sitting down.”

An adventure across Tuscany

Berruti dove onto the descent from Volpaia, leading Maddalena down the rutted road. The route bisected the fortified town, squeezing between walls just wide enough for a Fiat. Berruti never once dragged a foot, despite the inch-deep channels of water on the road and the loose gravel and hairpin turns.

Maddalena, riding a five-speed yellow Legnano from the 1950s, followed with Luzzana, just behind. He’d eventually join the pair at the bottom of the descent, while Leonardi refueled at the rest stop high on the hill. There, riders ate bunches of grapes plucked from the fields nearby and downed glasses of red wine and mineral water.

It was at one such rest stop that Berruti waved a small, aluminum bottle beneath my nose. “You think I’m joking,” he roared. “Here, smell!”

It was grappa, the horrid, distilled, 120-proof Italian beverage made from the leftover skins, seeds, and stems of grapes used for wine. He had been drinking grappa for the first 50km of the race.

By the time Berruti and his three companions neared the line, another 70km after the descent off of Volpaia, more than six hours after departing, the “winners” had changed, showered, and eaten a pasta meal prepared by the race organization. The town square in Gaiole had morphed into a scene from 100 years ago, complete with artisans pounding out horseshoes, vintage automobiles sputtering through the piazza, and a marching band providing the soundtrack for the festival honoring cycling and its champions.

The rain had stopped, and slanting, afternoon sunlight settled over the Chianti countryside.

Several hundred spectators crowded around the finish, craning necks and readying cameras to catch a glimpse of the hard men who had braved the day’s rain and hills. Around a gradual left-hand bend came Berruti. His fourth Eroica, finished, safe and sound.

Horns, cheering and wild applause greeted Luzzana, Berruti, and Maddalena. Leonardi, the oldest of the four, rolled through and quickly found a cigarette.

“Ah, I should quit, eh? ” he laughed, and added magnanimously, “It was difficult today.”

During the closing festivities, it seems as though I allowed the enthusiasm and emotion to overcome me, and I’ve committed to riding the Eroica in 2002. Andy Hampsten’s touring group, Cinghiale Cycling Tours, will end its Super Tuscan itinerary at the race next year on September 29, and word is the former Giro winner will ride as well.

I’ll go through with it, if only in the hopes of absorbing a little of the spirit that makes the Eroica what it is. See you in Gaiole in Chianti, next September. The gods willing.