One question that’s flooded my DMs during the Tour de France has been some variation of this question regarding road bike choice: Why aren’t the pros riding the lighter-weight bikes on mountain stages when given the chance?

What makes these aero bikes seem like the best bikes in the Tour de France? Is it that the aero bikes are that much faster that weight doesn’t matter? Or is it a question of comfort? And if those aero bikes are faster, how much faster are they?

We took to doing some sleuthing and asking bike brands and teams how the pros choose which bike they ride (when they have the choice), why aero bikes have all of this buzz after the all-around race bike seemed to take over, and ultimately, at what point the aero option becomes faster than the lighter one. Spoiler alert: the aero option is almost always the faster one.

How do teams choose between an aero bike and a lightweight climber’s bike?

My colleague Josh Ross covered this topic earlier in detail. Bianchi claims the tipping point for choosing the Specialissima climbing bike over the Oltre RC aero bike is a roughly 6 percent gradient for a pro-level rider. Above 6 percent, the weight savings of the climbing bike outweighs the aero gains of the aero bike.

This isn’t an uncommon number, as Cannondale cited the same ~6 percent or greater gradient as the tipping point for choosing the lighter SuperSix Evo rather than the heavier but much more aero at higher speed SystemSix.

Faster doesn’t mean better, however. The dearly departed SystemSix had a stiff ride, an expensive starting price compared to the SuperSix Evo, and fit geometry that precluded most non-pro cyclists from ever riding it. An uncomfortable bike is rarely a fast one, and what amounts to a ‘fast’ bike is different for everyone. As of today, the EF Pro Cycling Team now only has the latest SuperSix Evo to race with; it’s also claimed to be nearly as aero as that outgoing SystemSix, anyway.

The answers with other bikes and teams with two road bikes to choose from amounts to more of an “it depends.” Here’s Visma-Lease a Bike’s head of performance Mathieu Heijboer:

Each rider will be equipped with the optimal bike and wheelset tailored to their unique role, ensuring maximum efficiency and comfort from start to finish. By analyzing altitude gain, the positioning of climbs within the stage, and the steepness of every ascent, we’ll determine whether the aero-focused S5 or the lightweight climbing R5 offers the greatest advantage.

Different frame sizes mean different weights, which can shift the balance between climbing speed and aerodynamic gains—so the best choice may vary from rider to rider.

Read between the lines, and it appears there are two main reasons why a Jonas Vingegaard might stick to the Cervélo S5 aero bike on every stage, while a bigger rider like Matteo Jorgenson might choose the R5.

The first comes down to the stage gradient and the steepness of each ascent. While Visma-Lease a Bike won’t say which bike is faster at a specific percentage, based on the fact that just about everyone but Sepp Kuss rode the S5 through stage 18 of the Tour in the Alps, the S5 might be the faster bike, even on climbs over 6 percent.

The second bit comes down to bike size, however. The weight difference between Vingegaard-sized aero bikes versus climbing bikes is going to be much smaller than the difference between the two bikes for a taller rider like Matteo Jorgenson.

Just how much of a difference? We don’t have the weights of Jorgenson’s R5 build, but we can do some guessing here. His 58 cm bike Cervélo R5 weighed just 6.92 kg (15.26 pounds) with a computer, cages, and pedals, while Bikeradar reports that Vingegaard’s 51 cm S5 weighed in at 7.385 kg (16.28 pounds) with pedals, cages, and a computer. The bikes didn’t have the same wheels, but one could assume a size 58 cm S5 would add roughly 100-200 grams over the size 51 cm S5.

Going by that estimation, a 58 cm R5 and S5 can have as much as a 760 gram (1.5 pound) weight spread, but likely much less of a spread for a smaller rider. Does that weight matter all that much to the pros? It depends, as Heijboer said above. Jorgenson still opted for the aero-focused S5 on stage 18 of the Tour de France through the French Alps despite all the climbing after all.

So, despite that estimated spread in weight difference, the pros still opted for an aero bike in the French Alps. But why?

When is the aero option faster?

We’ve established that choosing the lightweight bike can result in big weight savings, particularly if you’re a bigger or heavier rider. We’ve also established that those weight savings are easily overridden by personal preference if you’re putting out WorldTour power numbers. But where is a lightweight bike faster, then?

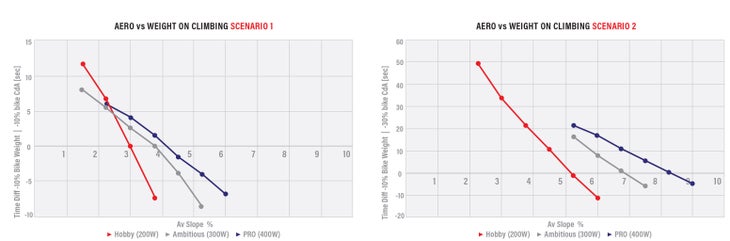

This study from Swiss Side – the company that recently released a wheelset that’s soon to be outlawed by UCI rule changes – dove into this very topic. While there’s plenty of interesting info from the study, the key takeaway is this: if you’re on a 5 percent or steeper gradient and you’re climbing at an effort of less than ~3 watts per kilogram, the lightweight bike (and the lightweight wheels) is the better option in the real world (scenario 2). Everywhere else, the aero bike is faster.

But what if you’re climbing at a higher power output? For a 70 kg rider (155 pounds) riding at 300 watts (~4.3 w/kg), the breaking point where the climbing option becomes faster is 6.8 percent or more. And at 400 watts (~5.7 w/kg), that gradient becomes a steep 8.3 percent. While the comparison focuses on wheels and the frame, the point remains: the aero option is almost always faster for pros, and likely faster for those of above-average strength.

The Mont Ventoux climb of stage 16 of the Tour de France comes at an average of 7.4 percent. Based on our power analysis, the power of both Jonas Vingegaard and Tadej Pogačar (who himself averaged an estimated 6.4 w/kg) means they should absolutely be on the more aero option, be it wheels or the aero frame itself.

In short, if you’re putting out the insane numbers of a Tour de France rider, you’ll almost always benefit from the aero bike, which is likely why both Pogačar and Vingegaard have opted for their aero bike options.

But if you’re a mere mortal putting out average power numbers? The aero option is still often the faster choice in a simulation, even up decently steep mountain climbs.

Why were we talking about ‘one bike to do it all’?

Let’s go back to 2020. Specialized, the company that popularized the term “aero is everything” with its Venge aero bike, failed to replace the second generation of its heralded aero bike with another. Replacing it was, well, the Tarmac. It claimed that riders preferred one bike to do everything, and that not only was it nearly as aero as the outgoing Venge, but it was over 1 kg (2.2 pounds) lighter.

Flash ahead to 2024, and Trek did the same, combining the Emonda climber’s bike with the Madone aero bike to make the eighth-generation Madone. The claims were the same: just as aero as the outgoing (and heavier) Madone, but claimed to be light like the Emonda.

Pinarello has done the one bike to do it all thing for quite some time, dating back to the Dogma F8 launch in 2014. While Factor technically has its O2 VAM climbing bike, the Ostro VAM is light enough that its WorldTour team Israel-Premier Tech is almost always on the more aero bike… that is, until it releases its own super aero bike.

2020 to 2024 saw a swath of new, lightweight race bikes that seem to do everything well. 2025, however, has been all about the aero bike, and why we seem to be having this conversation again.

The aero road bike was dead, right? All hail the aero road bike

Overall, the pros have ditched their climbing bikes when given a choice. And one team that seemed to still use its climbing bike – UAE Team Emirates – XRG – has seemingly ditched it at the Tour de France. Yes, Tadej Pogacar did use the Colnago V5Rs in parts of the Tour de France; our photography shows he’s been on the climbing-specific bike up until roughly stage 12 of the Tour.

Since then, however, Pogi has switched to a specially-prepped Y1Rs aero bike for the time trial and increasingly mountainous stages alike.

He’s not the only rider to ditch the climber’s bike. Climber Lenny Martinez has tended to choose an unreleased Merida Reacto aero bike rather than the climbing-focused Scultura road bike. Jonas Vingegaard regularly opts for the S5 aero bike in the climbing stages with lightweight climbing wheels rather than the lightweight R5 climbing bike.

Movistar’s Enric Mas regularly opts for the Canyon Aeroad over the brand’s lighter-weight Ultimate road bike. Canyon’s answer is a bit more nuanced, however. According to the brand, not only can riders take greater advantage of the gains made from an aero bike, but “there’s the added convenience for teams and riders of less bikes and less logistics.”

Now, this isn’t always the case everywhere. Ben O’Connor may have taken the queen stage win aboard the aero-centric Giant Propel rather than the climbing-focused TCR, but Giant still says that “For now, one bike simply can’t do it all.”

I could go on down the list, but you get the picture. As Josh mentioned in his story, most of these aero bikes can now get close to that magic 6.8 kg (15 pounds) UCI-imposed weight minimum for these bikes. With some careful weight shaving and a paint delete, even the somewhat weighty Colnago Y1Rs weighed in at a claimed 6.9 kg (15.2 pounds) with some serious gear choices. For the pros, the advantages of an aero bike outweigh the disadvantages.

No, the all-around race bike isn’t dead. Quit asking me about it

No, the all-around race road bike isn’t dead; there just hasn’t been one that’s captured cyclists’ imagination in some time.

BMC released a new version of its all-around race bike, the Teammachine SLR 01, partially because it found the Teammachine R to be too hard-edged for most riders. The resulting bike was one that is roughly 300 g lighter and a claimed 4.2 percent less aero efficient, which we’d estimate to be ~ 8 watts more required to maintain 30 miles per hour. It’s still an all-round race bike, says BMC, and an awfully good one to ride in our time with it. It’s just one that is slightly more approachable… and happens to fit the bill as a climber’s bike.

Yes, aero bikes are lighter than they ever have been, which allows the pros to ditch the climber’s bike more frequently than ever. Further, they’re more efficient aerodynamically than ever, making any edge a rider can find that much more important. And frankly, many of these aero bikes ride more comfortably on choppy surfaces than ever, too.

I wouldn’t be surprised to see more talk about one race bike to do it all next year; considering a new Specialized Tarmac has launched every year on a three-year cycle, I bet we’d see a new one for 2026. That’s the rhythm of these things, and the hype cycle will start all over again.

My take? Ride whatever bike you want. Ride the one that fits your needs, makes sense against what you and your friends like to ride, what you can afford, and importantly, what makes you happy. Most of these aero bikes have capabilities that are simply out of reach for most cyclists, anyway, while all-road bikes continue to be the right road bike for most riders.