The sport of cycling is faster than ever. Climbing records are broken nearly every week, and average speeds are getting higher and higher. Seven w/kg is the new 6w/kg when it comes to climbing speeds and threshold power.

What has changed over the past 5-10 years? A few inflection points throughout cycling history, some more dramatic than others, have led us to modern-day performance levels. In this article, we will examine a few of those inflection points, with a special emphasis on changes in training.

Cycling’s Evolution of Speed

The sport of cycling goes back more than 130 years. In the beginning, there was only one gear per bike, professional cyclists were also smokers, and no one had any idea what the word “ketone” meant. Fast-forward to the late 20th century, and cycling had become much faster. Riders are now wearing skin suits and aero helmets, they have multiple gears to choose from, and there is a new invention in carbohydrate-rich gels.

Professional cycling became much faster in the 1990s and early 2000s for various reasons (many of them against the rules), and many of those results have now been erased from the history books. As the sport cleaned itself up, climbing times became slower around the 2010s. But the pursuit of marginal gains was right around the corner.

That’s when Team Sky began its dominant run, especially at the Tour de France. The Team Sky train was feared throughout the peloton, and also feared by viewers who found it shamefully boring.

Team Sky/Team Ineos won seven out of eight Tours de France from 2012 to 2019. But then, everything changed.

The Modern Cycling Era

One of the biggest inflection points in cycling (and world) history was the COVID-19 pandemic. Events around the world were cancelled for most of 2020. Some cyclists weren’t even allowed to ride outside due to pandemic restrictions. Most riders ended up on the indoor trainer, and virtual cycling exploded in popularity. While some riders spent 2020 on the couch, others trained their butts off, putting in massive hours without interruption. This was also the perfect time for riders to try new things because there wasn’t an important race looming over their schedule. Altitude, carbohydrates, and heat training were tested over and over, with some riders showing high response rates.

This is where the modern cycling era began.

Tadej Pogačar, Jonas Vingegaard, Mathieu Van der Poel, Remco Evenepoel… These are some of the first names that jump to mind when thinking about modern cycling. These riders were some of the best in the world before 2020. But since then, they have brought the sport to an entirely different level.

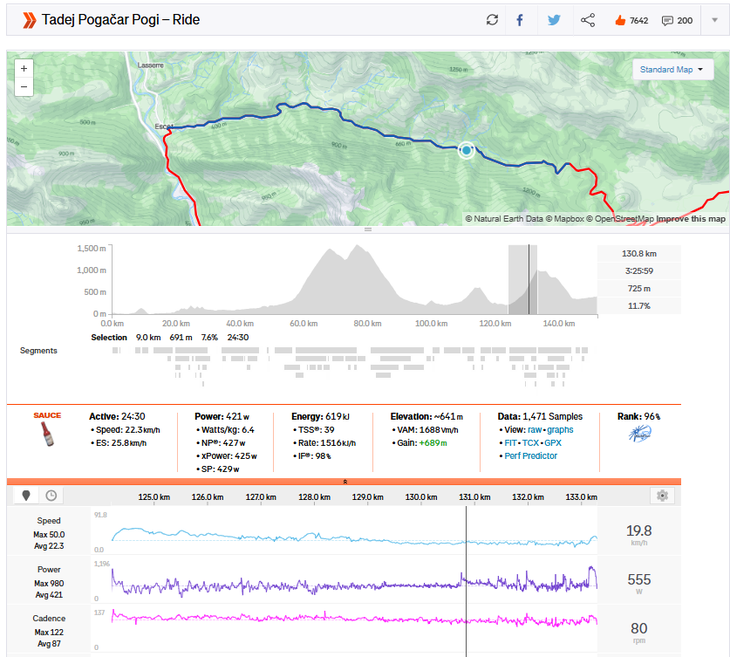

Back in 2020, Pogačar was still posting his power numbers on Strava. On September 6th that year, Pogačar won Stage 9 of the Tour de France in a small group sprint. He had attacked on the final climb of the day, the Col de Marie Blanque (7.3 km at 8.7%), and whittled down the group of favorites to only three: Primož Roglič, Egan Bernal, and Mikel Landa. On this climb, Pogačar averaged 421w (6.4w/kg) for 24 minutes, including the final 10 minutes of the climb at 457w (6.9w/kg).

Pogačar – Col de Marie Blanque (2020 Tour de France)

- Time: 24:30

- Average Power: 421w (6.4w/kg)

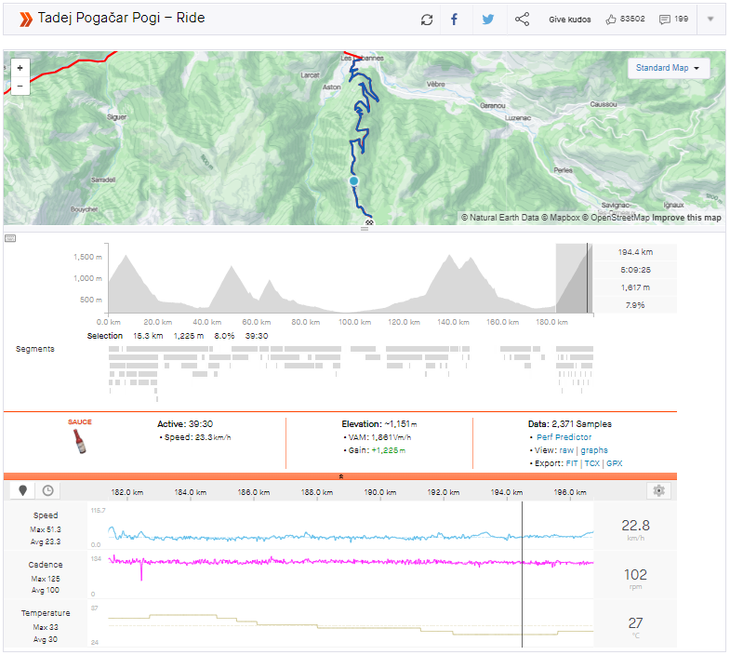

In 2024, Pogačar did roughly 7w/kg for 40 minutes on Plateau de Beille to win Stage 15 of the Tour de France. That performance is on a completely different planet compared to 2020. It was a much harder stage in 2024, and the climb was nearly twice as long as Col de Marie Blanque. Yet, Pogačar was able to do more than 0.5w/kg more for the entire climb.

Pogačar – Plateau de Beille (2024 Tour de France)

- Time: 39:30

- Average Power: 455w (~7w/kg)

Of course, several other factors have contributed to the increased speeds of modern cycling. Aerodynamics have improved lightyears, to the point where top riders are performing aero testing at least once or twice per year. Top-of-the-line bikes are tens of watts faster than only a few years ago, and tire technology has had more of an impact than most people realize. Wider tires have actually made cycling faster, as well as deep-sectioned rims, and 3-D printed handlebars.

The carbohydrate revolution also plays a massive role in the evolution of cycling speed, as has been discussed in previous articles. But let’s take a closer look at training in modern cycling.

Heat Training and Altitude

The latest and greatest addition to endurance sport training is heat. More specifically, we’re talking about specific heat training protocols that riders are using year-round to increase their performance.

It wasn’t long ago that heat training was only done before hot-weather races. Europeans racing at the Tour Down Under in January would undergo heat training protocol before entering the Australian heat. Tour de France GC contenders would go through heat training before competing under the summer sun. That makes sense.

But there is a lot more that can be gained from heat training other than the ability to perform in hot weather conditions. Our complete guide to heat training dives into the nitty gritty that comes with optimizing for heat training.

Now, professional cyclists are heat training year-round to maximize performance gains. Some perform heat training two times per week for the entire year, while others perform 2 to 3-week heat training blocks to maximize the adaptations.

There is a similar school of thought about altitude training. Ten years ago, riders would head to altitude 4-5 weeks before their goal race, such as the Tour de France. There, they would spend three weeks training at high altitude before returning to sea level just before the race. When done properly, they would have the best legs of their life for a few weeks following the altitude camp.

In modern cycling, riders are going to altitude camps multiple times per year. Some riders are going to altitude in January before the Classics, then again in May before the Tour de France, and then again in August before the World Championships. This places a large amount of stress on the body, but it can also stimulate physiological adaptations that help the rider find the best form of their life.

You cannot discount the mental toll of altitude training, too, as most riders do not enjoy living on a remote mountain for weeks at a time. They are often away from their families and far from the big cities, so there isn’t much to do other than eat, sleep, and train. This is perfect for maximizing performance gains, but it can also lead to psychological burnout.

Shorter Off-Seasons and Year-Round Intensity

Another piece to the puzzle is the addition of year-round intensity. Many riders are shortening their off-seasons, either by taking less time off the bike, returning to high-intensity intervals sooner, or both.

Rarely will you find training races anymore; by the time the neutral zone ends at Omloop Nieuwsblad, the peloton is ready to produce some of their best numbers. Riders cannot arrive at their first race of the season 5kg overweight anymore. Those days are long gone, and professional cyclists are staying fit nearly 365 days per year.

High-intensity training has been reintegrated into most off-season training programs, allowing riders to increase their fitness while only riding 10-20 hours per week. For a professional cyclist with nothing else to do, this is low-volume training.

But by incorporating VO2 Max intervals, 40/20s, and torque work into their off-season training, riders are starting their season at a higher fitness base each and every year.

Power Analysis data courtesy of Strava

Strava sauce extension

Riders: Tadej Pogačar