The Torqued Wrench: Good ideas gone awry

The Torqued Wrench is a new column from VeloNews.com tech writer Caley Fretz. Every other week he’ll tackle the rumors, trends, innovations, and underpinnings of the tech world — or something else entirely. You can submit questions to TorquedWrench@competitorgroup.com.

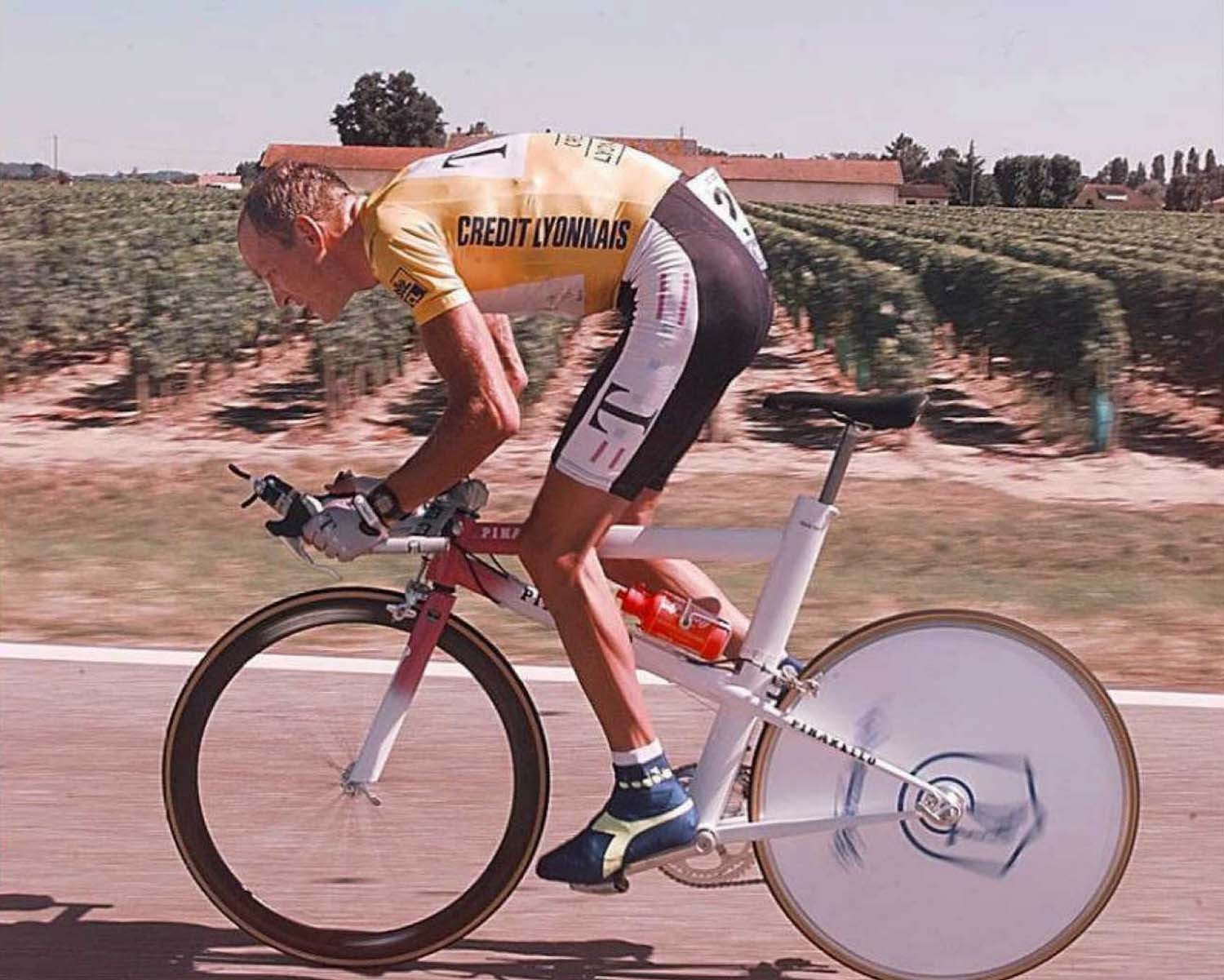

It is October of 1996, shortly after Bjarne Riis’ Tour de France victory. Cycling is in the midst of a technological revolution; carbon fiber permeates the professional peloton, allowing engineers to cast off the constraints of metallic frame building in favor of radical, wind-cheating designs.

The most refined race machines of the mid-1990s, particularly time trial bikes, are nothing like they were just a few years ago — it has been only seven years since Greg LeMond confirmed the supremacy of his aerobars aboard a steel Botecchia, yet in a mere eight months Riis will hurl his $20,000 monocoque carbon monstrosity into a field. The radical carbon “funny bikes” that have sprouted like weeds in the last few years may still have two wheels and a chain, but are otherwise unidentifiable as relations to their predecessors. They simply don’t look like bikes anymore.

Enter our bold heroes; our de-caped, button-down soldiers of tradition and institutional hardheadedness. The men, the myths, the legends: the Union Cycliste International.

A genesis in Lugano

Graeme Obree and Chris Boardman can attest to the UCI’s steadfast aversion to novelty in equipment or rider position. But it wasn’t until the late ’90s that the UCI tried to put its traditionalist tendencies into writing.

The Lugano Charter (pdf), penned in Lugano, Switzerland, in October 1996 and finally approved by the UCI in 2000, is the basis of the UCI’s technical rulebook (Part 1, Chapter 3, to be specific). That rulebook has remained largely unchanged over 11 years, though the text has been slightly amended a few times.

At its most basic, the charter was designed to uphold a rather noble ideal: Cycling should be a sport of athletes, not machines. Bikes should look like bikes, and equipment should be available to anyone — one-offs and prototypes should be barred to avoid the sort of technological arms race that occurred in the ’90s.

Lugano expressly outlawed the use of prototype equipment in competition. It also set parameters for the shape of bike frames and components, and put limits on rider position. It is the origin of the 6.8kg weight limit, the 3:1 tube profile, the horizontal saddle rule, and a host of other regulations created with the goal of maintaining the image and spirit of the racing bicycle.

Mission accomplished, right? Well, just like a similar declaration on an aircraft carrier nine years ago, it’s proving to be a bit more complicated than some would have you believe.

Good ideas, bad execution

Lugano’s overarching principle is sound. Limits have to be set somewhere — that the lines were drawn at 6.8kg, and 3:1, is not inherently wrong. Regulations are needed to prevent a downward plunge towards packs of racing recumbents, or splayed-out superman positions that offer insufficient control off the velodrome and in the real world.

Yet the Lugano Charter has been a disappointment, the unfortunate fallout of a blend of regulatory ambiguity and lackluster enforcement. It’s a collection of bad laws applied by uninformed cops.

The regulations themselves are vaguely written. Not unintelligible lawyer-speak, but language that is often so broad that engineers could memorize every rule and still have no idea whether their designs are actually legal. There are articles that could be used to outlaw or legalize just about anything.

Take Article 1.3.033, which bans “non-essential items of clothing or items designed to influence the performances of a rider such as reducing air resistance or modifying the body of the rider (compression, stretching, support).” You would think that this language would ban time trial helmets, which are just a non-essential fairing for your head. And yet, such helmets are completely legal.

When I asked UCI president Pat McQuaid about the ambiguity of the current rulebook last summer, he explained: “The regulations were written in a philosophical way. They were written by philosophical types.”

One would think that this admission would spur, at the very least, a conversation about re-writing the regulations.

“No, they will be clarified,” insisted UCI technical coordinator Julien Carron. Not re-written, just amended.

Enforcement of these broad rules has been inconsistent. McQuaid admits that many regulations “were loosely monitored by the UCI for a period of years, and manufacturers took advantage of that. It came to a head when Fabian (Cancellara) rode a bike in the Monaco Tour prologue that was outside regulations in a couple of ways.”

It was there that the UCI realized the sport was on a trajectory back towards the ’90s.

Commissaires are responsible for checking equipment at races, and disallowing anything against the rules. But their knowledge of the latest equipment, and of their own rules, has often been insufficient.

At the Giro d’Italia last year, I watched a commissaire try to disallow a Vacansoleil rider’s time trial bike because he believed the aerobar extensions were too long. He thought the rider’s SRAM shifters were of the return-to-center variety, requiring a measurement to the tip of the shifter blade. They were, in fact, regular time trial shifters, which are measured at the pivot. The commissaire had no idea what he was looking at.

The fix

Carron, the UCI technical coordinator, is well aware of the current rulebook’s deficiencies. Meeting the man and discussing the current technical regulations with him makes it abundantly clear that even he sometimes finds it all frustrating.

But the rules are not going anywhere, so he’s making amends.

Initially, he’s been clarifying some of the rules individually, as he did recently with the aforementioned level-saddle rule. That’s a good step.

Now, he’s designed a way to remove some of the rule enforcement at the start line. The “UCI Approved” sticker program, rolled out for frames last year, is essentially a mandatory pre-production check on equipment to ensure its legality. The UCI works with manufacturers to make sure equipment is legal before it ever rolls off the assembly line.

And the program may expand beyond frames “into quality and safety control,” Carron said when we met in August. “We may soon implement approval for wheels, clothing, saddles, handlebars and such. We may safety test for wheels with additional testing, on the brake track for example.”

There would therefore be no question as to the legality of a piece of equipment.

“If the equipment has the sticker, then (the commissaires) must just check the position of the riders,” Carron explained.

He even hinted that the 6.8kg weight limit could be tossed, since the equipment safety checks would make the rule redundant — which would be proof positive of the original charter’s spiral towards obsolescence.

The program will give the UCI the ability to make decisions about equipment behind closed doors, with plenty of time for deliberation. Interpretation of the current rulebook’s philosophical language will happen in one place, rather than throughout the world. In essence, it would solve the myriad problems presented by the current rules.

In good or bad faith

Of course, the program is far from perfect. The cost is significant and shouldered exclusively by manufacturers. It is unknown how much approval of equipment might cost down the road, but at present the charge for the full approval procedure for a given frame and fork costs 12,000 CHF, plus VAT. That’s about $13,000 at today’s exchange rate.

“Cost to manufacturers is dependent on cost of procedure,” said Carron. “We are just covering expenses.”

Is the program a good-faith effort to prop up the shortfalls of the Lugano Charter, or an attempt to move the costs associated with equipment regulation from the UCI onto the shoulders of the industry?

It’s simply too early to say. All we really know now is that yes, the new system should remove some of the regulatory ambiguity we’ve become accustomed to. And no, it is not going to come cheaply.

Weigh in in the comments below, or shoot me an email atTorquedWrench@competitorgroup.com.