Tokyo Olympics: How Team USA rebuilt the women's Team Pursuit squad for 2021

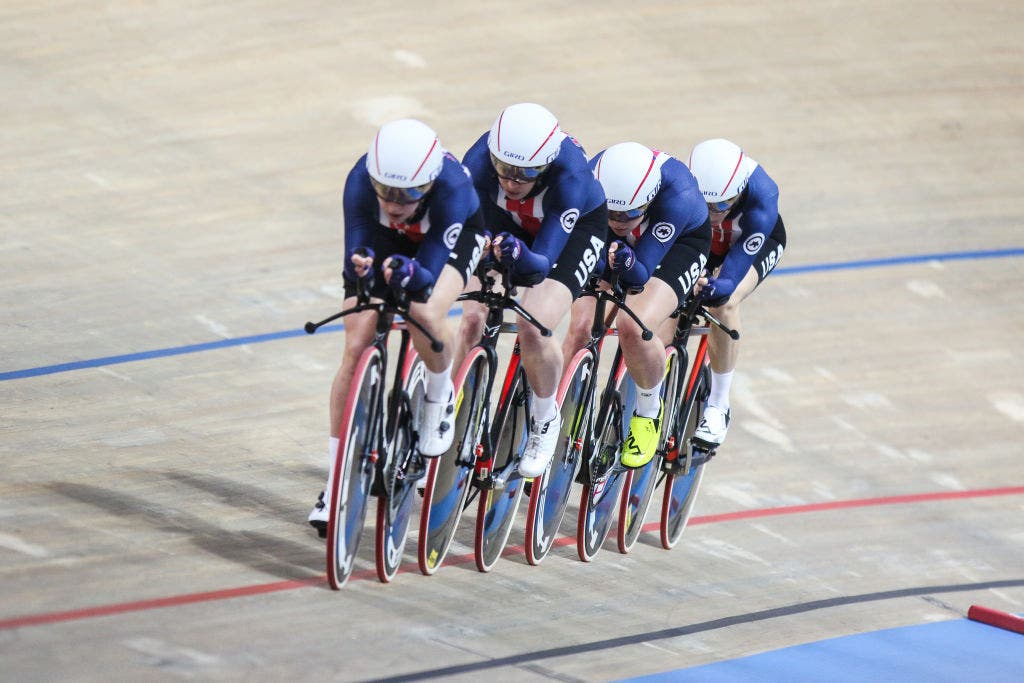

Track cyclists compete for the rainbow jersey for the first time since February 2020 in Berlin. (Photo: Maja Hitij/Getty Images)

The last time the U.S. women’s team pursuit squad raced in major international competition, smiles and tears made the emotion that much more intense from the winner’s podium.

In February 2020, just weeks before the world closed down in pandemic fears, the four-rider team delivered its most dominating and encouraging world title yet in the precision and watt-fueled race against the clock.

Yet there was a teammate missing: Kelly Catlin, the 23-year-old who died from suicide in March 2019. The U.S. team dedicated their ride to her.

“This one is super special,” said Chloé Dygert, who earned Rio Olympic silver on a team with Catlin. “This is our first world championship since Kelly. To win here, for her, it means a lot. It’s very emotional. We had her in our hearts this whole time.”

When the U.S. women’s team lines up in Tokyo later this summer, the team will have Catlin close to their hearts. In her absence, the team was forced to regroup and refocus. In something as precise and integrated, that’s no easy feat.

Longtime team anchor Sarah Hammer, who drove the team to back-to-back silver medals in 2012 and 2106, retired after Rio de Janeiro. Then, Catlin’s tragic death dealt a crushing blow to everyone inside the team. Dygert and emerging talent Jennifer Valente stepped up to provide leadership and restore the team’s ballast from the depths of disappointment and despair.

The women’s team pursuit squad, one of the most prolific and reliable inside USA Cycling’s wheelhouse for the Olympics, had to start from scratch. The team cast a wide net to round out the rotation. Emma White and Lily Williams were brought in, and after long hours on the track, slotted into the well-oiled machine. Replacing riders in a team pursuit, or bringing in new talent from beyond the track, already creates a challenge.

Having to replace a core rider under such emotional circumstances made the mountain to Tokyo even harder to climb.

Head coach Gary Sutton was especially moved. The legendary Australian track coach, who joined the American team in 2018, was overwhelmed with emotion on the infield in Berlin when he watched his crew power to gold.

“She just meant so much to everyone inside this team,” Sutton said of Catlin. “The way the team came together to win here today in the way they did says so much about everyone in this organization. I couldn’t be prouder.”

Flash-forward 16 months and the team is powering toward Tokyo even stronger and motivated than ever.

The goal remains the same — finally, win the gold medal.

Dygert, Valente provide the foundation

A lot has happened since the team powered so convincingly to gold in Berlin.

Literally weeks after the 2020 track worlds, international competition ground to a halt. The Tokyo Games were postponed, and everyone went into lockdown. The team hasn’t raced together since on the international stage.

Dygert, who has since emerged as a double-medal threat on the boards as well as in road in the time trial, suffered a horrific crash during the 2020 road worlds in Italy in September. While leading the women’s individual time trial, Dygert crashed heavily into a guardrail on a sweeping right-hander.

The impact left a grotesque gash on her left thigh just above her knee, putting her career in danger. A long winter of recovery and rehabilitation sees her back on track — literally and figuratively — just in time for a return to Olympic competition.

Jim Miller, the head of athletics at USA Cycling, is bullish on the team’s chances in Tokyo. Miller was the brain trust behind Kristin Armstrong and her three-straight gold medals in individual time trials, and he believes the team is on the cusp of greatness. Armstrong now works closely with Dygert, and everyone is optimistic the team will be in winning form in time to bring it all together in Tokyo.

Another key member is Valente, who, along with Dygert, is the only returning member from the Rio squad. She’s emerged as a medal threat in the endurance events as well, and will also race omnium in Tokyo.

“I still think I am young, but I am now the oldest on the team,” said Valente, 26, last year in Berlin. “We are working well together and we all know what the goal is.”

Unlike Dygert, Valente kept her most personal feelings and thoughts about Catlin close to her chest.

She wasn’t comfortable about speaking of the heartbreak, and worked hard to compartmentalize her emotions, and keep her focus on the task at hand. Valente was there in 2016 in Rio de Janeiro in a similar scenario as this Olympic cycle. The U.S. team stormed to the world title ahead of the Rio Games, only to be bested — again — by the team from Great Britain.

The British team will be strong again in the next Olympic cycle, but there are also challenges from Canada, Germany, and Australia.

“It’s not about beating Great Britain,” Valente said. “Everyone will be getting better before Tokyo. It’s about being our best and winning ourselves.”

Perhaps winning gold in Tokyo will be the best way to pay homage to Catlin.

Clicking into gear

The Olympic team pursuit is a four-member event that of all the cycling disciplines requires complete cohesion to properly function.

The team is only as fast as its weakest link, but the chain can be broken by anyone. Being too strong can almost be as bad as being slow. When it works, it’s a thing of beauty.

Many believe the latest iteration could be the one that pushes it across the line for Olympic gold. The U.S. women’s team pursuit is poised for glory this summer, fielding perhaps its best team since the discipline realized Olympic status in 2012.

With two silver medals — behind arch-rival Great Britain in both London and Rio de Janeiro — the team is primed to take the next step up. Rebuilding the team following the retirement of Hammer and the passing of Catlin wasn’t easy.

Stepping in to fill the gap were White and Williams, two relative newcomers to track racing. White was an established cyclocross racer, while Williams discovered bike racing after excelling in the mile distance as a runner.

The four-minute effort or so of team pursuit is eerily similar to the effort of the 1,500-meter running race. It fit Williams like a glove. In fact, the COVID delay has a silver lining, it’s allowed the two newcomers extra time to work on the track.

“The year delay because of COVID has been really good for me because I’ve now effectively doubled the time I’ve had to train,” Williams said. “I’ve had no distractions and all I’ve been doing is training to make the Olympic team. It’s my exclusive goal. I feel really lucky.”

Williams only started racing on the track in 2019, and though she’s also a road racer with Rally Cycling, the extra year delay allowed her to hone her track skills. White also took full advantage of the yearlong Olympic postponement and spent long hours on the track in Colorado Springs.

“The Olympic dream is so high up on all of our lists that we will do anything for it,” White said. “I’ve put so much pressure on myself to be where I need to be for my team – you kind of look forward to the relief when it’s all done. Every day you wake up and you’re thinking about the Olympics and every workout you have, every decision you make you think about that dream.”

Sutton is at the core of everything that’s happened.

The veteran Australian provided a steady hand during periods of tumult that threatened to overwhelm and sink the ship. Sutton believes and confides in his racing prodigies, and will be there alongside the boards.

“The way the team pulled together after everything that happened is something I almost don’t have words for,” said Sutton. “Everyone decided the best thing to do was to carry on and keep racing. They’re such fighters. I couldn’t be prouder.”

Last stop: Tokyo

A world pandemic, an unimaginable tragedy, and personal setbacks all made the core of the team even stronger. How they fare in Tokyo is anybody’s guess. Due to the global pandemic’s long stretch through 2020 and 2021, the U.S. Team Pursuit squad hasn’t participated in a race since the 2020 UCI world championships.

While they are coming into Tokyo without the recent experience of competition, they are coming in with plenty of experience. Throughout 2021 the squad hunkered down for months in Colorado Springs and Southern California to train together relentlessly in preparation for the Olympics. The Americans are hoping that these training sessions will make up for the dearth of competition.

Through the tragic events of Catlin’s death in 2019 to the interruptions caused by COVID-19, the team has tried to stay focused on the larger goal.

Tokyo still looms large, and everyone inside the team is working behind the scenes to arrive at the critical moments even stronger. This week Lily Williams, Chloé Dygert, Jennifer Valente, and Emma White will finally get a chance to shine. For the U.S. women’s track team, they’ll be racing for five.

“We don’t talk about it every day,” Dygert said. “When there is something going on that reminds us of Kelly, we’re not afraid to talk about it. There’s jokes, there’s everything. Kelly’s here, Kelly’s with us all the time.”