VN Archives: How the 176-pound Miguel Indurain crushed it in the mountains of the Tour de France

Editor’s note: Stage 9 of the 2020 Tour de France featured the fearsome Peyresourde, which Tadej Pogačar used to launch a stunning attack. The Peyresourde has often proved a decisive battleground, such as on stage 16 from the 1993 Tour, which pushed race leader Miguel Indurain to his limit.

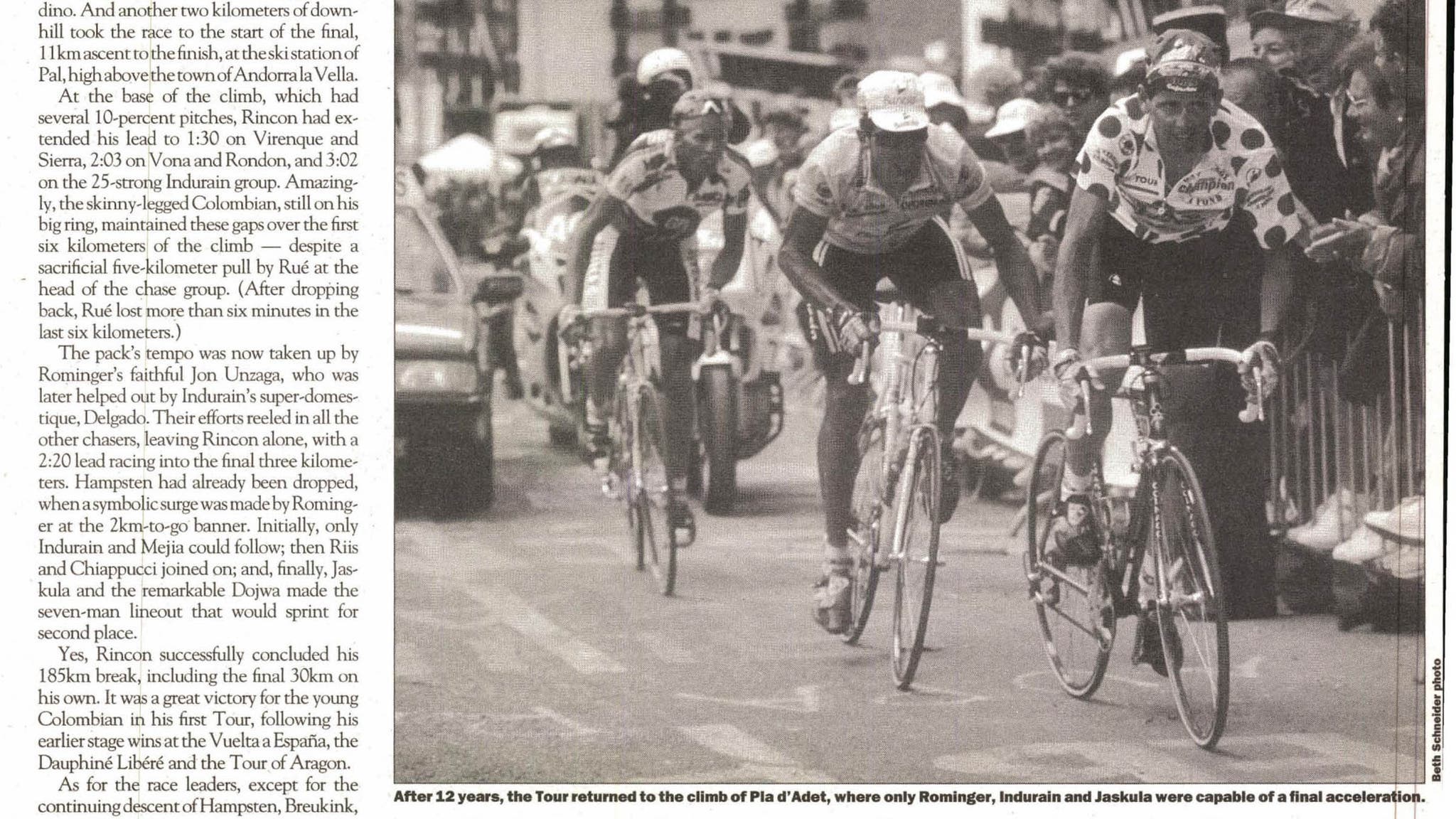

Tony Rominger kept his promise, Zenon Jaskula won his stage, Andy Hampsten rescued Mejia… and Miguel Indurain probably clinched the Tour: Those were the distinct results of a stage that lasted more than seven hours, but was played out on the final, half-hour climb to Plad’Adet, 3,000 feet above the stage town of St. Lary-Soulan. The classic finishing climb — which was the setting for Lucien Van Impe’s winning move in the 1976 Tour — was last used by the race 12 years ago. Its return was long-awaited by Tour connoisseurs…

The promise that Rominger kept was to keep on attacking. The stage won by Jaskula was the first ever by a Pole. Hampsten displayed selfless professionalism to keep his Motorola teammate Mejia in second place overall. And the race leader was taken to the limit in defending his yellow jersey. “It may look easy,” a relieved but exhausted Indurain said after the finish, “but I still have to carry my 80 kilos (176 pounds) up every hill.”

The hill up to Plad’Adet is as tough as they come: steeper than L’Alpe d’Huez, with long, straight pitches, on a narrow road that angles across a sheer cliff face. And virtually the whole climb was visible to the front group of 25 riders as they made the flat, valley approach. Also visible were the countless thousands of fans, many of them Spanish and Basques who’d brought their huge flags to wave for Miguel.

Upon approaching this hill, Rominger had three Spanish teammates alongside him — Unzaga, Escartin, and Javier Mauleon — who’d worked a steady paceline in the 15km of valley roads leading to St. Lary. Their tempo prevented any surprise attacks, and put Rominger into perfect position for this final ascent. As for Indurain, he had been riding on teammate Bernard’s wheel, following Rominger and the three CLAS riders.

After Escartin and Mauleon peeled off, Unzaga led Rominger, Indurain, Mejia, and Jaskula up the first slopes of the 10km finishing climb. Also moving toward the front were Roche, Hampsten… and Millar.

The wily Scot, in search of his fourth career Tour stage win, had looked up and seen that after about two kilometers of climbing, the crowd-jammed road turned sharply left, where the present headwind would become favorable. Describing the situation, Millar recounted, “I was moving up, and wanted to attack in the tailwind, and then Rominger did it. It was hard to move up in the crowd.”

So the ideally placed Rominger blasted out of the tailwind turn, belatedly chased by Indurain, who had Mejia on his wheel. The race leader did catch the flying Swiss, but Mejia slowly lost ground, and was joined by Jaskula. Rominger attacked again, but the yellow jersey once more found the inner strength to close the gap.

Meanwhile, Millar had found a way through, and now charged by Jaskula and Mejia, and closed to within 10 meters of Rominger and Indurain. “But I couldn’t close the 10 meters,” Millar lamented. “And if I couldn’t close those 10 meters, I couldn’t win.”

As the climb continued, with several pitches of 10 and even 12 percent, Jaskula was the next to try to bridge. The blond Pole had been close to winning at Isola 2000, where he said that winning a stage was more important to him than finishing the Tour in second or third place. After all, a Tour stage had never been won by a Polish racer.

These thoughts were on his mind when the GB-MG-Bianchi rider stamped harder on the pedals, literally sprinting past Millar, to slowly close on the two leaders. And he did make it across to Rominger and Indurain, to form a three-man break, seven kilometers from the finish.

At the same time, Millar dropped back to the flagging Mejia, while Roche — still looking for a stage win in his final Tour — came rocketing up to them. A time split showed that this new trio was 15 seconds behind the three leaders, and 15 seconds ahead of Chiappucci. Following the Italian was Hampsten, who had been steadily working his way forward.

Over the next 300 meters, the elegant American swept up to the Mejia group — now 30 seconds behind the leaders; and after tapping his Colombian teammate on the shoulder, Hampsten went to the front of the group, wanting Mejia to follow him. But Mejia did not respond, and looked blankly at his colleague when Hampsten offered him a bottle. Clearly, all Hampsten could do was set tempo for his weary teammate — which he did with utmost devotion.

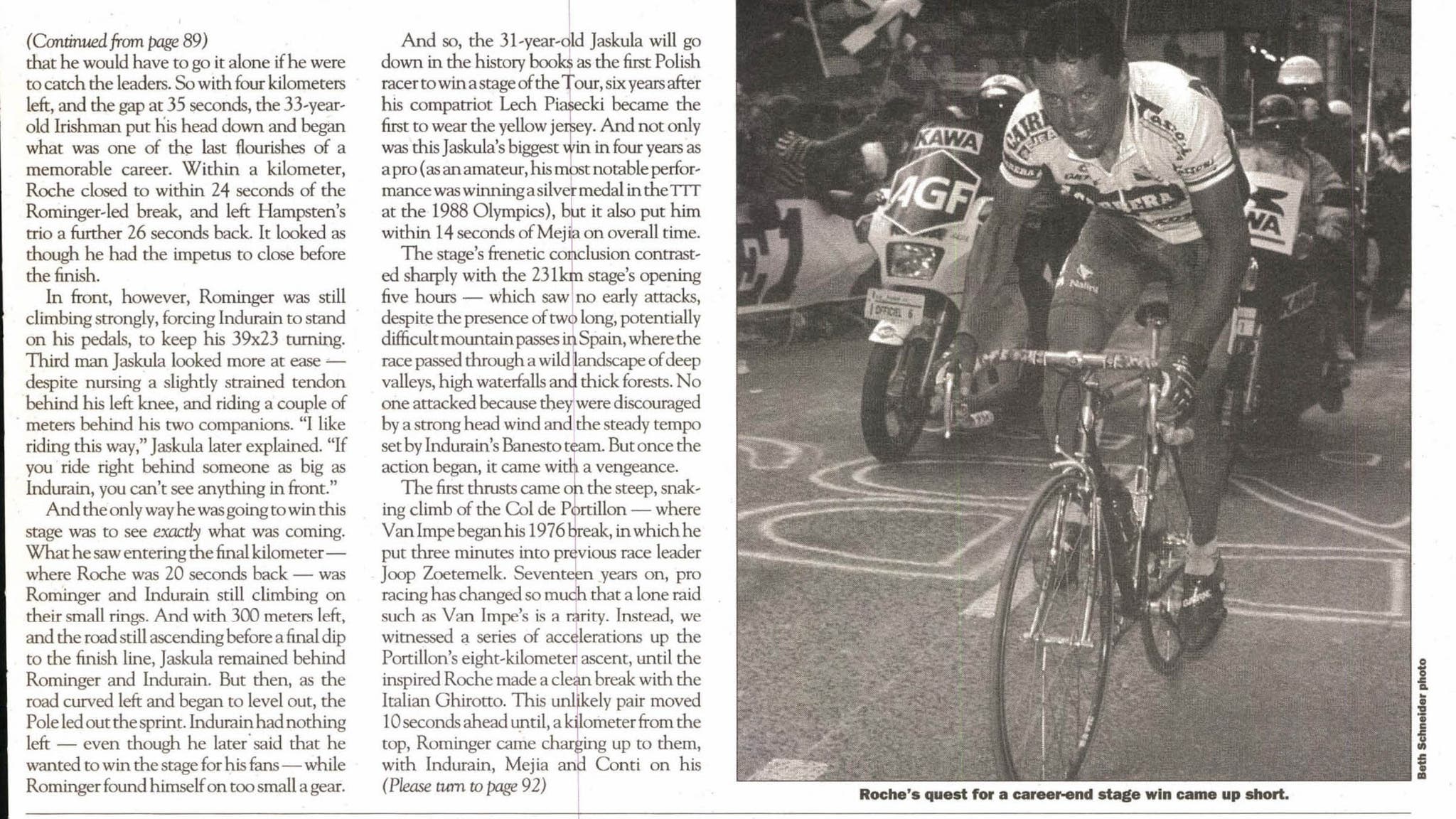

Seeing all this happen, Roche realized that he would have to go it alone if he were to catch the leaders. So with four kilometers left, and the gap at 35 seconds, the 33-year-old Irishman put his head down and began what was one of the last flourishes of a memorable career. Within a kilometer, Roche closed to within 24 seconds of the Rominger-led break, and left Hampsten’s trio a further 26 seconds back. It looked as though he had the impetus to close before the finish.

In front, however, Rominger was still climbing strongly, forcing Indurain to stand on his pedals, to keep his 39×23 turning. Third man Jaskula looked more at ease — despite nursing a slightly strained tendon behind his left knee, and riding a couple of meters behind his two companions. “I like riding this way,” Jaskula later explained. “If you ride right behind someone as big as Indurain, you can’t see anything in front.”

And the only way he was going to win this stage was to see exactly what was coming. What he saw entering the final kilometer — where Roche was 20 seconds back — was Rominger and Indurain still climbing on their small rings. And with 300 meters left, and the road still ascending before a final dip to the finish line, Jaskula remained behind Rominger and Indurain. But then, as the road curved left and began to level out, the Pole led out the sprint. Indurain had nothing left — even though he later said that he wanted to win the stage for his fans — while Rominger found himself on too small a gear.

And so, the 31-year-old Jaskula will go down in the history books, as the first Polish racer to win a stage of the Tour, six years after his compatriot Lech Piasecki became the first to wear the yellow jersey. And not only was this Jaskula’s biggest win in four years as a pro (as an amateur, his most notable performance was winning a silver medal in the TTT at the 1988 Olympics), but it also put him within 14 seconds of Mejia on overall time.

The stage’s frenetic conclusion contrasted sharply with the 231km stage’s opening five hours — which saw no early attacks, despite the presence of two long, potentially difficult mountain passes in Spain, where the race passed through a wild landscape of deep valleys, high waterfalls, and thick forests. No one attacked because the were discouraged by a strong headwind and the steady tempo set by Indurain’s Banesto team. But once the action began, it came with a vengeance.

The first thrusts came on the steep, snaking climb of the Col de Portillon — where Van Impe began his 1976 break, in which he put three minutes into previous race leader Joop Zoetemelk. Seventeen years on, pro racing has changed so much that a lone raid such as Van Impe’s is a rarity. Instead, we witnessed a series of accelerations up the Portillon’s eight-kilometer ascent, until the inspired Roche made a clean break with the Italian Ghirotto. This unlikely pair moved 10 seconds ahead until, a kilometer from the top, Rominger came charging up to them, with Indurain, Mejia, and Conti on his wheel. Chiappucci and Hampsten also made it across, and the resultant nine-man group began the descent 25 seconds before fifth-placed Riis — who soon caught back.

Meanwhile, a daredevil downhill attack had projected Chiappucci and Ghirotto ahead by 28 seconds, causing the eight chasers to continue their efforts all the way up the penultimate climb, the Peyresourde. Among those caught out by the accelerations was alpine stage hero Millar, who later admitted, “I made a mistake on the hill before. They attacked, and I thought it would come back on the descent — but it went away. So I had to ride (hard) on the Peyresourde to come back.” Indeed, Millar — at the head of a 12-strong chase group which also included Delgado and Alcala — had to overcome what was a 1:20 deficit at the Peyresourde’s base.

By the summit, Chiappucci and Ghirotto were still 20 seconds ahead of the Rominger-Indurain chase group — which was about to be joined by Millar’s dozen. The two leaders were swept up on the easy descent, so with 25km to go in the stage, there were 25 riders in front… and everything to fight for.