The Science of the Modern Base Season: Why Zone 2 Isn’t Enough Anymore

The intensity of races such as Gent-Wevelgem underline the importance of good early season form (Photo: Gruber Images)

15 years ago, you would have looked like a lunatic if you were doing 40/20s in December. Everyone would scoff at you – coaches, riders, trainers, and staff. You were on a fast track to burn out. “Have fun crushing the January team camp,” and “Good luck peaking in February,” would be overheard.

But now, every professional cyclist is doing intervals in December. After enjoying a 2-4 week off-season, they’ll be back on an island in the Pacific crushing tempo and VO2 Max intervals. Why?

Zone 2 isn’t enough for the base season anymore. Training has evolved, so much so that if you only rode easy over the winter, you might never catch up to the level of your competitors. In this article, we’re going to dive into this new training style: what has changed, the benefits (and risks), and how the pros are doing it.

Old School Base Training

It wasn’t too long ago that the best cyclists in the world would show up to January training camp out of shape and 5kg overweight. These were Tour de France winners, world-class sprinters, and Classics legends, all enjoying the holidays at home before the “real” work began.

Starting January 1st, they would train the house down, putting in 25-35 hour weeks at training camp, with little to no intensity. They would ride in Zones 1-2 all day, sometimes as long as eight hours.

Eventually, they would start inching towards race shape. By March or April, they would line up for their first race. But they were usually in terrible form, just getting through the race as training before moving onto the next one. After a few months, they would be in very good shape, ready to peak for the Tour de France in July.

It was a slow buildup to a short peak. But for many riders, it worked.

Modern Day Base Training

Today’s professional cyclists cannot afford to only perform in July. Instead, they need to perform for 6-9 months, typically March to October. Some riders (such as those in Australia right now) start racing in January and won’t finish their season until the Tour of Guangxi in mid-October.

A high number of race days is both a blessing and a curse. Every professional cyclist wants to race, but with racing comes many risks. Race too much, and you could easily burn out, incapable of unlocking your peak performance due to accumulated fatigue. Race days also come with travel, days away from home, and the risks of crashing or illness.

On the other hand, more race days means more opportunities to showcase your abilities. If you race 70 times a year, you have 70 opportunities to help your teammates, make the breakaway, or go for a race-winning move. Race 35 times per year and you cut your opportunities in half.

So that brings us to modern base training. While race days are certainly a factor in driving the revolution, they are only one piece of the puzzle. Another is pure physiological benefits.

Why Year-Round Intensity Makes You Faster

High-intensity training is a double-edged sword. You need it to get faster, but too much of it will make you slower than ever. We have seen plenty of pros in the best form of their life completely burn out and disappear from the results sheet. There are plenty of factors at play here, but overtraining and over-racing are two of the most common.

We’ll get to the risks in a minute, but first let’s examine why HIIT training works.

High-intensity training boosts your aerobic and anaerobic abilities. It shortens recovery between efforts, and gives you the high-end, punchy fitness you need for racing. This ability also decays quite quickly. Two weeks without a VO2 Max interval, and you can lose that high-end fitness for a period of time. But you can also maintain that punchiness with regular high-intensity interval training.

The key is that modern training has spread out high-intensity training blocks. In the past, riders might have done a three-week, high-intensity altitude camp before a goal race. They would train their endurance all winter, and then go to training camp where they would do 4-5 HIIT sessions each week.

Today, riders will do two high-intensity weekly, almost year-round. Instead of concentrated HIIT blocks, the intervals become more spread out, allowing the rider to maintain “race-level” fitness for a longer period of time.

High Intensity Winter Workouts

When it comes to winter training, there don’t seem to be many differences between December and April intervals. WorldTour high-intensity sessions focus on sprint ability, torque production, lactate clearance, VO2 Max development and more. The amount of specific sessions that you can do is endless, but there are two threads that I see tying almost every WorldTour rider together: torque and VO2 Max.

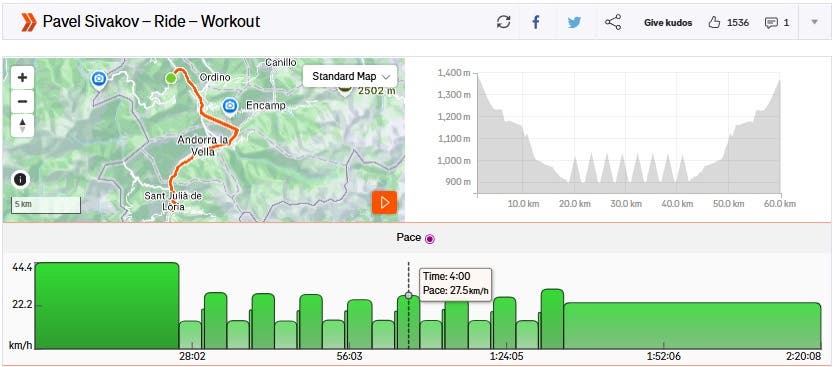

The modern peloton loves torque sessions, which means low cadence, high power intervals. You can do 4min torque intervals or 15min torque intervals, the choice is yours. But it seems like most WorldTour riders do three sets of 4-10 minute torque intervals at 40-50 rpm. Here is an example from Pavel Sivakov, a UAE Team Emirates-XRG rider who is known for his ability to peak, especially for the Tour de France and Road World Championships.

In this session, Sivakov did eight repetitions of high-torque intervals, likely around his threshold power. Each interval finished with a 30sec burst at 60 rpm where Sivakov was riding at 20 kph up a 12% grade. If I had to guess, that is somewhere around 500-600w for 30 seconds.

Sivakov – Torque Session

Sivakov’s Winter Torque Workout

Time: 2.5 hours

Intervals: 8x (4min at 45pm into 30sec at 60 rpm)

Intensity: 45 rpm intervals at ~400w, 60 rpm intervals at ~500w

Another key aspect of high intensity training is VO2 Max, a magical buzzword used by many and understood by few. There are a million different ways to train your VO2 Max, but the most common way is to perform VO2 Max HIIT with a 2:1 work-to-rest ratio. That could mean 30/15s, 40/20s, or two minutes on with one minute off.

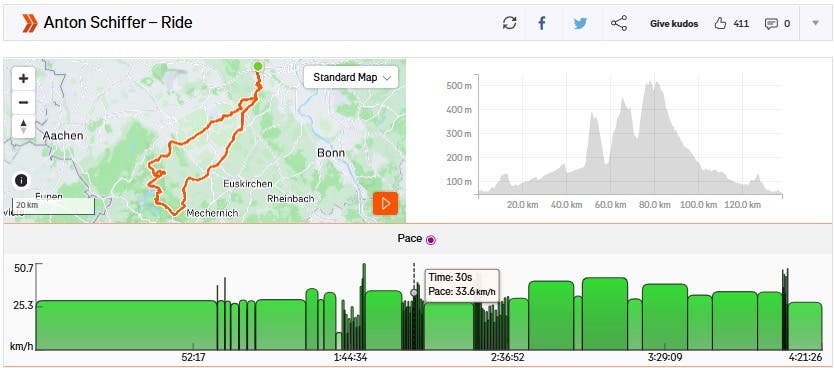

One of the new recruits for Visma-LAB this year is Anton Schiffer, who switched to the team’s coaches in December. In the workout below, you can see how Visma LAB uses different types of VO2 Max intervals in the same ride: 40/20s, 30/15s, 30/30s, and 4min efforts all in the same session.

Schiffer’s Visma LAB VO2 Max Workout

Time: 4.5 hours

Interval #1: 4min on, 2min off, 4min on

Interval #2: 8x 40/20s

Interval #3: 10x 30/15s

Interval #4: 10x 30/30s

Interval #5: 4x 10sec on, 20sec off

In addition to the riders who perform high-intensity intervals all winter, there are many riders who continue to race. Superstar Mathieu Van der Poel is the standout name, a rider who races cyclocross throughout the winter after completing a long road season. Or is cyclocross preparation, rather, for the road season? Most likely it is all one big circle of training for Van der Poel.

CX requires Van der Poel to ride nearly all-out for an hour, which is much harder and more taxing than a typical HIIT session. Even so, Van der Poel is known for his ability to peak for goal races. The Dutchman might stay quiet for a few months in terms of results, but then he will turn up to Milan Sanremo able to follow Tadej Pogačar.

Perhaps, there lies the key: Van der Poel’s ability to turn it on or off multiple times a year. He can train hard for months in order to peak, but as soon as he needs time off, he switches into vacation mode. If you follow him on social media, you’ll see him on the beach in Dubai or playing golf in New York. That physical and mental recharge must be key for Van der Poel, and it makes you wonder how many other riders are missing that.

The Risks of Year-Round Intensity

Modern cycling is more scientific and structured than ever. Many pros weigh their oatmeal in the morning, track every calorie they burn, and upload it all to their team’s proprietary nutrition app. This isn’t only happening during the Grand Tours; this is happening at December training camp.

Power meters, breathing straps, heart rate monitors, sleep trackers, and smart watches track every movement a rider makes throughout the day. Any ounce of fatigue or illness must be measured and calculated as quickly as possible. Trainers, coaches, and nutritionists work around the clock to manage their riders in an attempt to help them unlock peak performance.

But the reality is, tracking everything can make you worse. Overdoing anything – nutrition, recovery devices, hard training, altitude – can lead to physical and mental burnout. We see it every year in professional cycling. Just think of a young rider that was crushing it in 2024, yet you haven’t heard their name in over a year.

More often than not, these young riders got some results, made it onto a big team, and then trained their faces off when the motivation was at an all-time high. They might have peaked at January team camp, and then completely burnt out by February. But when your contract says you’re a professional bike racer, you have to keep racing.

These burnt out riders keep racing for 6, 7, or 8 months, never allowing their body or mind to fully recover. Young riders can lose entire seasons to burn out, and many teams don’t have the patience to let them rest without putting an early end to their contract.

Getting things right

Career longevity is not at the forefront of professional cycling. Instead, we have 19-24 year old riders coming into the professional ranks thinking they have nine months to prove themselves. Most riders get 1-2 year contracts, and if you don’t perform in the first year, you get moved to the bottom of the renewal totem pole.

Of course, training hard makes you faster. But it has to be administered in the right dose to maximize your performance in the long-term. Think of it like caffeine – caffeine will make you faster, but only when you have the right amount at the right time.

If you never have caffeine, you’ll never know the benefits that it could give you. Have 300mg of caffeine half an hour before a time trial, and you will feel the difference.

But remember, more is not always better. If you start having 1000mg of caffeine every day, you will no longer get a performance boost from it. In fact, you’ll probably get slower due to all the side effects of high caffeine intake. The same goes for high-intensity training – the performance boosts are real, but only when given at the right time in the right dosage. So keep training your Zone 2 in the winter. Add in some intervals, but only 1-2 times per week.

Remind yourself of the long-term vision. The goal isn’t to train so hard that you burn yourself out in a year. It’s to build a staircase of fitness that levels up year after year. The off-season is the step on the staircase, the point at which your fitness levels out after a multi-month training and racing period. Then you can add a step each year, a jump in fitness from one level to the next.