The drivetrain wars: A history of shifting

But Juy pressed on, through an economic depression and World War II. Finally, in 1949, he hit the big time when Fausto Coppi won the Tour de France with a Simplex derailleur.

The following year, however, Campagnolo introduced the Gran Sport and ushered in decades of drivetrain dominance. Other brands came and went. SunTour certainly made a splash. But it wasn’t until Shimano made inroads toward the end of the 20th century that Campagnolo had a competitor who was on equal terms.

Then SRAM entered the road market in 2006 with its new Force and Rival drivetrains, featuring DoubleTap shifting logic — one paddle for shifting on each lever, with a short throw ending in a click for a shift to a harder gear, and then a longer throw to a second click for a shift to an easier.

A year later, SRAM’s top-of-the-line Red group was released, giving pros and consumers a viable third option, and the ensuing competition saw quality from all three brands go up while weights and prices came down. The competition meant consumers benefitted from continual innovation: wider gear ranges, lighter weights, and new technologies like electronic shifting.

As was the case back in Juy’s day, pro cycling, and especially the Tour de France, are key marketing platforms. In fact, while Juy was able to get by for years without professionals riding his equipment, these days, drivetrain brands need pro sponsorships to survive. The competition is so fierce, existing brands are entering the drivetrain space simply so they can continue to compete on other fronts, which brought us to this particular embarrassment of riches.

According to Rotor co-founder and chief innovation officer Pablo Carrasco, his company might not have even created its own group if not for the cutthroat nature of team sponsorships. Rotor established itself as a manufacturer of chainrings but found that it needed a complete group just to stay on pros’ bikes. “We had teams riding our chainrings, but they had other drivetrain sponsors who were always putting pressure on them to use their chainrings,” Carrasco said at last year’s Eurobike trade show. “They were always trying to kick us out.”

The difficulty now, unlike when the modern derailleur was invented, is that so many possibilities are locked down in patents. Rotor, for example, settled on hydraulic shifting after finding no way around the various patents for mechanical and electronic systems. “In the end, some patent or another was stopping us at every step,” Carrasco said. “Then it became clear that electronic was here to stay. So we had to do something that would let us offer something different and that would be one step ahead.”

SRAM’s engineers can tell you a thing or two about navigating that minefield. “There were 44 pounds of patents we had to work through — three feet of paperwork,” says Brad Menna, the SRAM Road Product Manager in charge of the new wireless eTap group. “But we wanted to come up with a drivetrain that would be a different solution from electronic. We didn’t have an electronic drivetrain, and we saw what was out there, and we knew we needed to be innovative. A lot of it was, ‘How do we better serve the rider but also get around those patents?’”

With so many shifting systems available, it’s hard to imagine what’s next for drivetrains. Here’s a look at the technological leaps that set the stage for the modern drivetrain wars.

Parallelogram rear derailleur

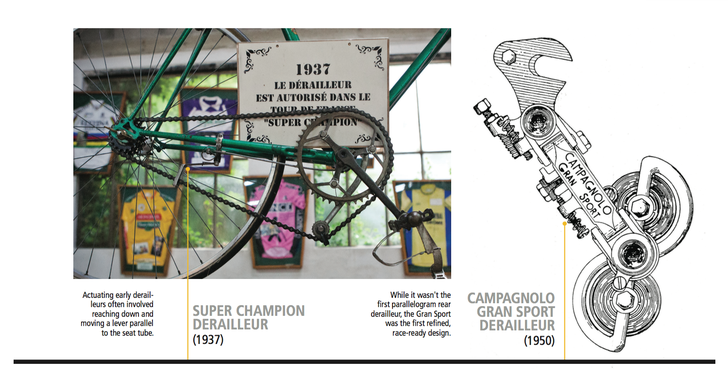

Juy and his contemporaries — companies like Huret and Cyclo — may have been the multi-gear pioneers, but what we think of as a derailleur didn’t come along until several years later.

Tullio Campagnolo is often credited with creating the first parallelogram rear derailleur, but that’s not entirely accurate. He was, perhaps, the first to popularize parallelogram rear derailleurs intended for racing, but Nivex, a small company that had the misfortune of developing this revolutionary device during the pre-World War II recession, can claim to be first on the scene.

Campagnolo dominated the world of derailleurs for decades after with the Gran Sport. The parallelogram design revolutionized shifting because it allowed the chain to move left and right while remaining parallel to the cogs. The streamlined motion meant smoother, more confident shifting. While the early days of the parallelogram design saw a flurry of imitators, Campagnolo became the dominant drivetrain force and remained so even after Shimano debuted to the world in the 1960s.

Around the same time that Shimano came on the scene, SunTour introduced the slant parallelogram derailleur, which it patented. This design improved on the regular parallelogram by keeping the distance between the jockey wheels and the gears both small and consistent, for much more precise shifting.

SunTour was innovative, even though its research and development department was quite small compared to Shimano’s. But quality control became an issue, and while consumers were still likely to want SunTour on more affordably priced bicycles, high-end users preferred Shimano for its meticulous execution, even if it was more expensive. SunTour reached its peak around 1982 then began to decline as Shimano took steps toward refining its products and dominating the market. And when SunTour’s patent expired in the 1980s, Shimano and Campagnolo were free to copy the design, sealing SunTour’s fate. By the early 1990s, consumers had gotten the impression that SunTour just wasn’t as good as Shimano, and the brand largely disappeared from showroom bikes.

Front derailleurs

The first front derailleur was, simply, a rider’s hand. He would reach down and move the chain from one sprocket to another, which required balance and skill. Most racers used a single chainring up front for simplicity and did all shifting, if any at all, in the rear, though the floating chain — a chain long enough that the rider could move it between chainrings and cogs of varying sizes — allowed the use of several rings up front for more gear combinations. Since multi-gear bikes weren’t allowed in the Tour de France until 1937, touring bicyclists were the most likely riders to be using such systems.

It’s hard to say when the first front derailleur was created, though iterations of the concept appeared fleetingly in the early 20th century, then disappeared. Once again, Lucien Juy asserted his presence in 1949 by introducing the Simplex Competition front derailleur, which was operated by hand using a lever that extended upward parallel to the seat tube. Simplex had other variations on this design as early as 1946, and in 1952 the company introduced a cable-operated model. In the first half of the 1950s, Huret released its Competition group that included a cable-actuated front derailleur; both the front and rear shifters were mounted on the right side of the bike so the operator could shift either derailleur with one hand.

The front derailleur opened up more gear combinations for riders tackling varied terrain and, just like that, it became a standard component in almost all drivetrains until 2012, when SRAM ushered in the “one-by” era. It started in the mountain bike world: a single chainring up front paired with a wide-range cassette in the rear (a 10-42-tooth rear cassette made up for the lack of a small chainring up front) simplified shifting by eliminating the front shifter entirely.

The one-by design hasn’t caught on in the road world just yet, but SRAM is in the pro cess of trying to push the front derailleur off of modern bikes and into the history books. Racers have been resistant to such change, citing larger jumps between gears in the wide-ranging rear cassette, resulting in more dramatic ratio changes with each shift.

Index shifting

If the slant parallelogram had been Shimano’s only step forward in the 1980s, it’s doubtful the company would have overtaken Campagnolo. But it was also in the 1980s that the Japanese brand introduced index shifting. Instead of using the shifter’s friction to let the rider find each gear and hold it there, with index shifting the levers clicked into place.

The idea wasn’t exactly new. SunTour had a click shifter as early as 1969, and others had made attempts at the concept later in the 1980s. Shimano introduced the technology in 1977 with Positron, an indexing system that was integrated into the rear derailleur. It was overly complicated, especially since it was marketed toward beginners. It relied on two cables for derailleur movement — or, alternatively, one thick cable that could both pull and push. Fortunately, Shimano Indexing System, or SIS, followed closely behind.

SIS moved the indexing into the shifter, allowing riders to find the right gear with a positive click — no more searching for the perfect spot on the cassette. The shifter rotated around a center point — the mounting stud on the frame — just like friction shifters. But an added circular ring with notches clicked into place against another ring cut with spaced indents. This system controlled how much the derailleur moved in either direction and indicated to the rider when the shift was complete. Early SIS shifters could be run either as an indexed system or as a simple friction system by turning a ring mounted on the outside of the shifter. It was exponentially better than Positron, in terms of performance and simplicity. But perhaps more importantly, it introduced the concept of system integration.

With traditional friction shifting, any derailleur could work with any shifters. With SIS, Shimano derailleurs had to be paired with Shimano shifters because the indexing meant a certain amount of cable pulled per click. Using a non-Shimano derailleur with a Shimano indexed shifter could result in a shift that landed between gears. That was the beginning of the modern concept of a “group” and the start of the proprietary market we know today.

STI

Down tube shifters seem retro and romantic, but if you were riding bikes before 1990 — meaning you were using down tube shifters simply because there was no other choice — you know just how much Shimano Total Integration (STI) changed the game.

STI, which Shimano debuted in 1990, combined the shift and brake levers into a single unit, giving riders more control and stability — hands always on the bars, no awkward reaching toward the down tube. The brake lever acted as both a brake actuator and a shift paddle. To brake, pull the lever as usual; to shift, push it inboard. A second paddle behind the brake lever shifted gears in the opposite direction when pushed inboard. While the design led to larger hoods — all the indexing mechanisms and hinges for the additional paddle were mounted within the brake lever — and a higher price, due to the intricate shift mechanism, consumers embraced the new design for its ease of use, simplicity, and stability resulting from a steady hand position during shifting and braking.

Around the same time, Campagnolo was working with the Sachs company on the Ergo-Power integration system, which worked differently than STI but which was based on the same principle: hands on the bars at all times. Unlike STI, Campagnolo’s shifters featured three levers for three actions: the brake lever actuated the brakes only — no inboard movement as in STI — while a paddle mounted behind the brake lever shifted the gears in one direction. Another paddle mounted on the inboard side of the brake hood actuated shifts in the other direction. The ErgoPower shifters allowed riders to “dump” gears, or shift many gears at the same time with a long throw of the shift lever.

While Campagnolo had dominated the drivetrain market for decades, Shimano’s STI now made it a major player in the drivetrain game, and today it is the foremost drivetrain manufacturer in the world.

STI wasn’t the first integrated shifting. Joel Evett, a passionate cycling enthusiast and woodworker from Massachusetts, developed an integrated shift/brake lever in 1975, well before STI hit the market, and even shopped his idea around to the major manufacturers of the time, starting with Campagnolo (which, according to Evett, passed on his idea, thinking the industry wasn’t ready for such a thing).

When VeloNews caught up with Evett in 2007 for an article on his prototype shifters, he told the story of a lot of doors knocked on, but not many answered. He eventually made his way to Shimano, which asked for a set of Evett’s shifters, then returned them after several months, without comment. Evett never heard word from the company again.

Not long after, Shimano released its STI levers and even cited Evett in the patent, though they never compensated him or admitted that they had used his idea. The company maintains its STI system is far different from Evett’s and that it did not steal his idea. When reached for comment in that same 2007 article, Devin Walton, Shimano’s media relations officer at the time, reaffirmed this: “I guarantee that he was not the first to think about shifting from the brake levers,” he said. “He may have gone further with it than anyone before, but to say we stole his idea negates all of the engineering that went into our levers.”

Evett disagrees. But regardless of who bears the title of STI’s inventor, there’s no doubt it revolutionized shifting.

Electronic shifting

Shimano’s Di2, which debuted in 2009, may have popularized the idea of electronic groups, but it wasn’t the first on the market. Mavic, now known primarily for wheels, holds that distinction. In 1992, the French company introduced the first hard-wired consumer electronic shifting system, called Zap.

The group had its quirks. First, only the rear derailleur shifted electronically — the front derailleur shifted mechanically with a cable — and even that isn’t an accurate representation of how it worked. The electronic signal from the shifter merely activated a solenoid in the rear derailleur. Once the solenoid activated, it released a ratcheting bar that dictated the lateral movement of the derailleur. The bar only moved, however, if the derailleur pulley was moving under pedaling load, which meant the shift wasn’t electronic at all. It was entirely mechanical. Shifts were reliable, but they could also be slow: if the rider pedaled unconvincingly, the pulley turned slowly, and the ratcheting bar also, consequently, moved with too little power. Conversely, faster pedaling meant faster shifting. Reliable, yes. Convenient and race-worthy, no.

That turned out to be Zap’s fatal flaw, and in 1999, Mavic introduced a supposedly more refined group called Mektronic, which also happened to be wireless. It was a significant step backward and met a dark fate quite quickly. Radio interference caused ghost shifts, the massive, bulky brake hoods were not UCI-legal, and lag time between pressing the shift buttons and the shift itself could range anywhere from a quarter-second to two seconds.

Don’t expect another iteration from Mavic anytime soon. Given the fierce competition from SRAM and Shimano in the original-equipment market, and Campagnolo in aftermarket sales, Mavic’s potential gains in the drivetrain world are admittedly slim. “Sadly, we don’t have the intention to re-enter the drivetrain market,” says Chad Moore, Mavic’s brand manager. “Who knows what the future holds, but for now we are laser-focused on our core business. But…you never know.”

Those other brands have Mavic to thank for their electronic successes: in terms of proof of concept, Mavic showed not only that electronic shifting had potential but that wireless systems could make a lot of sense.

Shimano was paying attention. In 2009, the company succeeded where Mavic had failed, in part by not being wedded to the idea of a wireless setup. Instead, the company developed a wired system that connected the shifters to each derailleur, providing direct contact that made it easier to deliver smooth shifting, reliability, and lighter button action. It worked so well that Dura-Ace Di2 quickly became the new standard in bicycle drivetrains.

Around the same time, Campagnolo was developing Electronic Power Shift, or EPS, which it debuted in 2011, the same year Shimano released its Ultegra Di2 group. Both Shimano and Campagnolo chose to stick to the same shift layouts they had used previously. In Campagnolo’s case, this meant a paddle behind the brake lever shifted in one direction and a thumb paddle mounted on the inside of the hood shifted the other way. The two systems, though different in operation, accomplished the same goal: precise, nearly effortless shifts at the touch of a button.

Wireless shifting

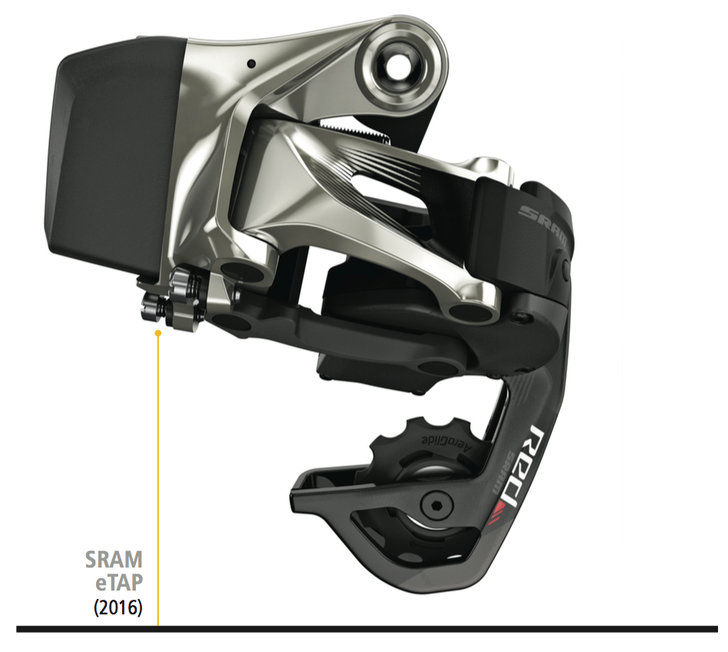

The next big leap forward was SRAM’s eTap, which eliminates all wires from the drivetrain system. Installing a complete group takes mere minutes. No wires means no routing, which means no internal ports, external guides, or other frame design concessions. It is, in essence, a successful iteration of what Mavic attempted with Mektronic. SRAM did much better, though, in part by developing and rigorously testing its own wireless signal to prevent the interference that plagued Mavic.

But there’s more to eTap than just the lack of wires. The group completely rethinks the logic of shifting. The decades-old idea that one side of the bars controls the rear derailleur and the other controls the front was born of mechanical necessity rather than intuition. While Di2 preserves this functionality, eTap completely dismisses it. There is just one paddle on each side. The right hand shifts to a harder gear, and the left one shifts to an easier one. Hit both at the same time to shift the front derailleur.

The new group also works on any road bike, making it perhaps the most backward-compatible drivetrain on the market. Put it on your 1970 Miele and it will work the same as it will on your 2016 Trek Madone. Install, pair, ride. That simplicity will be tested in the WorldTour in 2016 on Katusha and Ag2r La Mondiale bikes.

SRAM’s is not be the only wireless group in play, however. Just ahead of Eurobike 2016, FSA revealed an electronic drivetrain that is partially wireless.

Hydraulic shifting

While Rotor executives admit that the choice of hydraulics was a pragmatic way through the patent minefield, they claim there is no compromise in terms of performance with Uno, which was in development for five years.

“We felt that by using hydraulics to transfer energy, we would achieve low friction, low weight, and little to no maintenance,” says David Martinez, Rotor’s head of engineering. While installation will obviously be complicated — we imagine few mechanics are looking forward to bleeding drivetrains — Uno is a closed system and should, in theory, require little upkeep once installed.

Of course, all things old are new again. Uno shares some similarities with Shimano’s Positron system, in that the indexing is located at the derailleurs, though in a much more refined execution.

“The mechanical indexing is placed down at the derailleurs instead of with the shifters,” Martinez says. “This yields shifting accuracy and leaves room at the shifter to integrate the braking system. To the point, oil gets pushed from a master piston at the shifter to a slave piston in the derailleur, which actuates the indexing.” Rotor has not released details yet on how the indexing in the rear derailleur works.

We’ve only had a few minutes with it, but Uno seems to shift more smoothly than traditional mechanical systems, especially with the sharp bends that are common with internal routing, as there’s no cable friction to contend with. As for long-term reliability, keep an eye on Dimension Data, which is racing on Uno-equipped bikes this season.