Shoulder separations explained

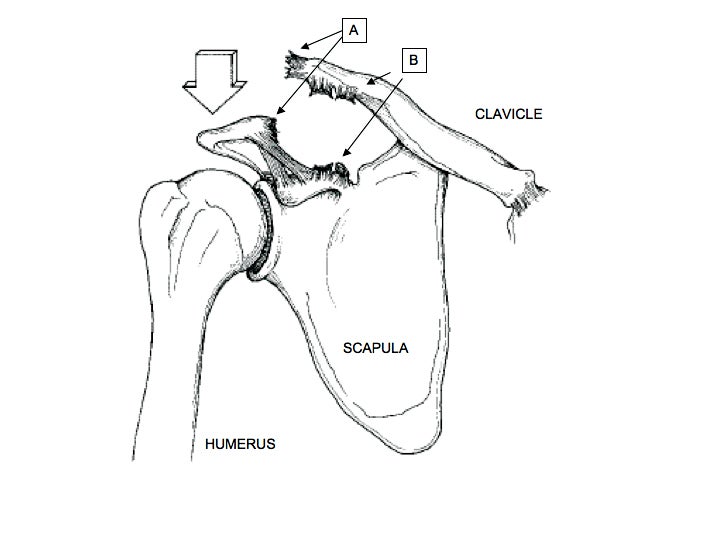

FIGURE 1: Shoulder separations occur when a downward force (ARROW) disrupts the normal ligaments (A & B) connecting the clavicle and scapula. Photo courtesy Dr. Meininger

The brisk fall air, the feel of your treads slipping to find traction in the moist grass, and that moment you know you’re going down … hard!

Cyclocross season is upon us and nothing is more exhilarating. Though with recent injuries to Danny Summerhill and Todd Wells, some crashes aren’t without consequence. As we wait and wonder what will happen to Summerhill’s world championship dreams, I sought out to answer: what is a shoulder separation? And why do some need surgery?

Shoulder separations are the most common injury in off-road cycling. Most commonly riders “endo” over the handlebars in an unexpected fall or collision. Falls are often so sudden that riders are unable to get their arms in front to brace themselves, landing; rather, on the point of the shoulder.

The force of hitting the ground pushes down on the shoulder, while the rider’s momentum carries them forward (FIGURE 1).

Depending on the severity of the injury, ligaments will stretch, partially tear (or sprain), and then completely tear leading to several different types of shoulder separations.

The shoulder is actually made up of three bones: the clavicle (collarbone), shoulder blade (scapula) and upper arm (humerus).

Technically speaking, a shoulder separation is a sprain or dislocation of the clavicle. A pair of strong ligaments holds the clavicle and scapula together forming what is called the acromioclavicular or “AC” joint. While little motion takes place through the AC joint, it is the only bony attachment of the upper extremity to the body. An AC joint sprain (or Type I separation) involves stretching of one set of ligaments; while Type II is a complete tear of only one ligament (FIGURE 1: A).

On the other hand, the most common variety (Type III) includes complete rupture of both ligament complexes (FIGURE 1: A & B); entirely disconnecting the collarbone from the shoulder blade. Without the support of the clavicle, the weight of the upper extremity pulls the scapula down, further separating the two bones and leading to the characteristic xray findings (FIGURE 2). Rarely, the end of the clavicle can actually poke through or become entrapped within the muscles of the shoulder (Type IV).

Riders who suffer a shoulder separation in a crash will complain of pain on the top of the shoulder, difficulty moving the arm (especially across their body) and will likely be unable to continue riding. Often times bruising or road rash on the point of the shoulder will also be present. Depending on the grade of injury, a deformity or tender bump on the top of the shoulder will be obvious.

A thorough physical examination and xrays are required to make the diagnosis and rule out more serious injuries such as a fracture. Occasionally an MRI may also be necessary to further evaluate the torn ligaments and the rotator cuff muscles; or ensure the tip of the clavicle is not entrapped in muscle. Once confirmed, the arm is placed in a sling to support the injured shoulder. Most shoulder separations, even completely displaced Type III, can be treated without surgery. Short term bracing with a sling, rest, ice, anti-inflammatories and physiotherapy are usually all that’s necessary.

Orthopaedic studies have shown that surgery for Type III shoulder separations yields no better results in the long term than non-surgical treatments for most people. While not yet proven, some sports medicine surgeons believe an operation to repair the torn ligaments, or restore them with graft tissue, may help high demand athletes return to their highest level. More severe Type IV injuries where muscle or soft tissues are trapped between the collarbone and shoulder blade require surgery as they are otherwise unlikely to heal and regain stability. From the accounts published in VeloNews and Summerhill’s Twitter page; it seems doctors are trying to determine if his injury is Type III or IV.

In our practice, we allow collegiate athletes to return to competition once they can participate without pain and have regained range of motion. Patience, however, is paramount as most athletes will complain the injured shoulder may be noticeable for up to six months. Rehabilitation, ice, range of motion and strengthening of the shoulder muscles are important to continue throughout this period.

While more rare, true shoulder dislocations can also occur in falls associated with cycling. In fact, mountain bike crashes are one of the most common causes. The difference; however, is that a dislocation involves separation of the ball and socket joint (like a golf ball falling off a tee) where the humerus meets the scapula. Riders commonly reach with an outstretched arm to brace their fall and the impact forces the shoulder out of joint. These are often quite dramatic injuries that require medical attention (and often times anesthesia) before they can safely be put back in place. Even after that, patients will require a sling for up to six weeks or even surgery to repair the torn ligaments.

In the case of shoulder injuries, the old adage rings true that an “ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure,” so use your head, stay safe and ride on! Let’s enjoy this cyclocross season together.

“Dr. Alex” is a Denver-native and an Orthopaedic Surgery Sports Medicine Fellow at the University of Chicago. When he’s not taking care of athletes, you might find him in an Elvis costume on the Cat. 3 start line of the Chicago Cyclocross Cup races (www.chicrosscup.com).