Welcome to the Urbanist Update. My job here might be as tech editor, but I’ve also spent tons of time studying transportation, city planning, and engineering. Here are some of the things I’ve found interesting over the past week related to biking in cities, cycling infrastructure, and urbanism.

What is urbanism? In short, it is the study of how the inhabitants of an urban area interact with their towns and cities. If you care about building sustainable communities that let you live a happy and healthy life, then this is the spot for you. See previous Updates here.

Ocean Avenue Curb-Protected Bikeway Ready for Its Close Up

Say the name ‘Ocean Avenue’ to me and my immediate thought would be to that sweet, sweet Yellowcard single. Now I can’t get this concrete extrusion machine thing out of my head.

The City of Santa Monica tweeted a short video of what basically looks like a 3D printer for separated bike lanes. For the most part, it kind of is a massive 3D printer. But rather than going back over and over to make layers like a 3D printer, an extrusion machine takes that concrete or asphalt mixture and pressurizes it through a mold. It’s much closer to piping a cake with frosting using a shaped tip, you know, besides all the concrete and much larger scale.

First shared by Santa Monica Next, using this extrusion machine is multitudes faster and more resource-efficient than the typical process of pouring concrete and shaping by hand with tools as is typically done. The extrusion machine created five blocks of concrete barriers – over 3,000 feet – for protected bike lanes in one day. All in one day folks!

How did the city get to these fancy protected bike lanes? It was a process, duh. Ocean Avenue had painted bike lanes for years, but it wasn’t until the city installed protected bike lanes with bollards in 2020 that they started to see changes.

According to the city, Santa Monica saw that just adding bollards decreased auto traffic by 18 percent while cyclist volumes increased significantly to the tune of five or even ten times more cyclists than previously. The massive concrete extrusion machine sped things up and adds even more separation between drivers and people biking.

The video got around as a “why can’t we do this?” call to action across the U.S. But the thing is, more likely than not, your city could probably already do this, provided it’s not already using it to reinforce highway construction.

RTA webinar discusses benefits and models for mobility hubs (in Chicago)

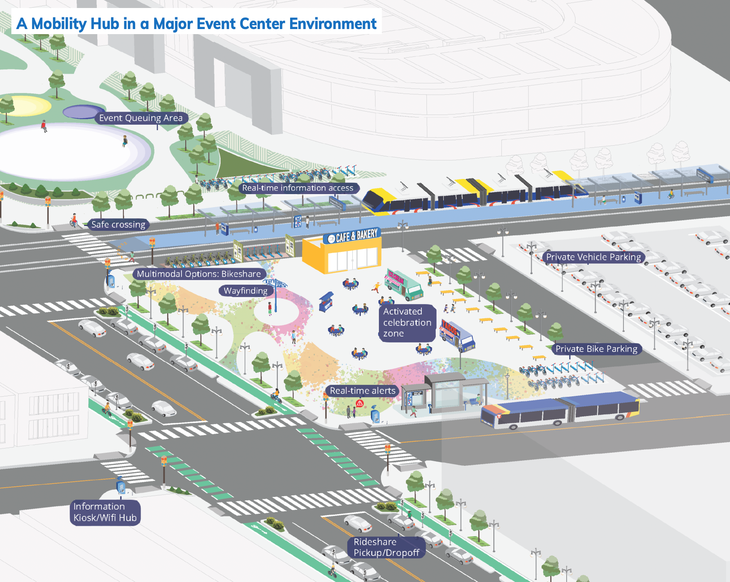

Chicago’s Regional Transportation Authority is undergoing a series of webinars for their new transit strategic plan dubbed “Transit is the Answer.” What I think is most interesting here – and evidently, Sharon Hoyer at Streetsblog Chicago thinks the same – is the idea of mobility hubs.

A mobility hub isn’t anything all that new, or really all that different from a transit hub one might have in a city. Major train stations are often transit hubs, as they have several bus lines, taxis, subways, light rail, or other ways to get around clustering in one location. A mobility hub takes those transit hubs and adds a focus on bikes, scooters, and active transit in general.

What does that focus look like for Chicago’s plan? Rather than one big hub where everything converges, these mobility hubs would be smaller, more frequent, and much more community-based. They might have bike share programs, bus lines, basic bike repair, and non-profit car-sharing services (like Colorado Car Share) focused in one area, but they could be as simple as a bike share dock with a coffee shop attached if necessary.

There are a few examples of this succeeding in other places. Bremen, Germany’s Mobil.punkt system is probably the most prominent one. The goal of it was to get people out of needing private car ownership through a number of mobility hubs around the city. Mobil.punkt hubs at a minimum have bike parking and a slew of parking spaces earmarked for car sharing systems, with clear signage and easy accessibility from the street. Larger stops offer secured, locked bike parking, tram and bus stops, and space for bike share and electric scooter share stops too.

Is a mobility hub coming to your city next? Maybe, but probably under a different name. Austin, Texas essentially placed a bunch of food trucks and tables by bus and light rail stops to good effect. Could a taco truck be enough for you to lower your car dependency? We’ll see. Maybe Chicago should put a bunch of Italian beef sandwich stands in their mobility hubs to get people out of their cars.

These are the 10 most bike-friendly cities in the world (and nine of them are in Europe)

The 2022 Global Cycling Index recently dropped their list of the most bike-friendly cities in the world. Let’s find out what they have in common.

The story reported by Euronews is obviously congratulatory to Europe. Bremen, Germany, home of the Mobil.punkt mobility hubs I mentioned earlier, is ninth on the list around the world. This is thanks not only to those hubs but also by creating “bicycle zones” in the city where bicycles have priority over cars on the road.

Hangzhou, China is the only non-European city to crack the top ten. One of their hallmark successes is their Urban Public Bicycle Sharing Program, which offers a comprehensive system that is free for the first hour for city residents. Bicycle dock locations are placed by bus stops, pubic parks, and points of interest across the city, with protected bike lanes and bike paths designed with those stops in mind.

The results are tremendous: 280,000 passengers are served daily by a massive 78,000 public bicycles, with an even split of usage between men and women. 96 percent of trips are free to the user, and 95 percent of the public are satisfied with the program.

There are many ways for a city to be bicycle friendly. Bike paths and roads are an obvious choice, but a massive – and largely free – bicycle share system helps too.

Oh, and the most bike-friendly North American city goes to Montreal, Quebec in 16th place. Portland, Oregon comes in at a rumbling 40th. Here’s the full index if you’re curious.

So Much for ‘Carmageddon’ (Philadelphia edition)

Yeah, we’re gonna talk about the I-95 highway collapse.

Last week, a bridge section of Interstate 95 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania collapsed under the intense heat of a tanker truck caught on fire. The collapse was devastating: several died in the incident, be it from falling debris or from the tanker explosion itself. And then there’s the roadway collapse itself, which should be a problem considering it is one of the most used roadways on the East Coast of the U.S.

Was it Carmageddon? Not quite, at least according to a story in the City Observatory.

In light of the loss that happened here is the idea that auto traffic is malleable and dynamic. People driving will change their behaviors based on what the roads look like. Drivers can choose when they travel, where they go, take alternative routes, or even avoid those trips altogether.

Really it is the opposite of the idea of ‘induced demand,’ which states that more road capacity produces more traffic. Are you missing a way to get from one place to another? Provided there is a connected, functioning roadway system, you’ll find a way to get to where you need to.

I bring this up because of how often people mention that creating space on roads for bicycle and walking infrastructure will cause car congestion and chaos for everyone involved. It might cause a bit of necessary changes to travel, especially if you’re given only one way to arrive at your destination. Most cities are constructed with the car being the only way to get around; I understand the fear.

But the value of designing our cities not only for cars but for everyone else is the opportunity to get around with an array of options. Find yourself in gridlock while driving? Take a bike, or a bus, or whatever you need to. It isn’t about banning all cars, it’s about giving people smart, efficient, and convenient ways to travel.

It is a shame that this I-95 collapse happened. A reliance on only one method of travel made sense before the Industrial Revolution. It doesn’t have to happen today.

@velosonja Theres a time and place for having to “take the lane” (ie when your city doesnt have complete infrastructure and you’re “bridging the gap”), but if we want to get more people on bikes, we need all ages and abilities infrastructure to make it happen. #biketok #bikelife #womenwhocycle #gobybike #cycling #bikejoy #bikeinfrastructure #activetransport ♬ Wes Anderson-esque Cute Acoustic – Kenji Ueda

Let’s talk about ‘vehicular cycling’

You’ve probably asked yourself, how have we gotten here? Why do people think it’s okay to allow a ‘Share the Road’ sign for cyclists on a 45 mph road? Why is cycling to places I want to go so uncomfortable? These and many other questions can be answered by learning about the idea of vehicular cycling.

Velosonja on TikTok does a great job summarizing why we have to fight so hard to take space back for separated bike lanes and infrastructure. In short, the theory says that cyclists need to integrate into street traffic just as much as cars do. If you act like a car, you’ll be treated like one. Cycling becomes safer and there’s no need for protected bike lanes and dedicated cycling infrastructure, at least according to the theory.

Vehicular cycling in practice doesn’t quite work like that, however, at least not in the year of our lord 2023. Cars are heavier and faster than ever. Drivers are more distracted than ever. And perhaps most importantly, as Velosonja notes in their video and I’ve noted previously, it places the blame and responsibility for a cyclist’s safety purely on the cyclist and not the driver.

I am a confident cyclist who feels more comfortable than the vast majority of folks in taking the lane and participating in vehicular cycling. But there are several scenarios I would never do what I do if I was with a new cyclist, a young child, or someone less able than me.

Make a system that is easy to use and people will do it. Vehicular cycling is anything but easy.